|

The White Whale's Talisman

© 2007 Sally Drumm, used by permission

[Images:]

I must down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull's way and the whale's way where the wind's like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover,

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick's over.

Friends and loves we have none, nor wealth nor blessed abode,

But the hope of the City of God at the other end of the road.

— John Masefield, The Seekers,

Over naked truth is a diaphanous mantle of fantasy.

— Inscription on statue in Lisbon honoring Jose Queiroz

The center of the earth finds itself in Ecuador. There, the equator begins and ends its 24,901-mile bulging stretch around the globe. Near Ecuador's capital, Quito, a monument stands marking the point where the equator divides the earth into two halves. One could say this monument created a manmade navel for the earth. A stone tower topped with a globe rises to the sun from this spot. From this earthly navel, four pathways lead in each cardinal direction. From one's position at this manmade center of the earth, any direction may be chosen from which to embark on one's next adventure. A person can stand for a moment in Eternity by placing one foot in the Northern Hemisphere and the other in the Southern Hemisphere. Perhaps for just this purpose, the builders of the monument inlaid a six-inch wide red stone line running east to west. In Ecuador, a person can straddle the world in a single step by riding the serpent that devours its own tail in a stretch around earth. While standing in both halves of the world, a person does not notice the earth spinning one thousand miles per hour. Most people do not often consider the earth's powerful rotation as the harbinger of night and day. The average person straddling the world in Ecuador does not think of the earth revolving around the sun in a circuit lasting about 365 days, or 595 million miles traveled each year at 18.5 miles per second. The movement of the earth seems as imaginary as the equatorial line itself. People do not usually consider themselves voyagers on the great ship Earth, sailing through space at 18.5 miles per second. Most people mark the beginning of existence by their own navels and measure the world only by the circumference of the bodily space they occupy, or by dimensions of experience, of personal joys and sorrows. Some people measure their world only by the number of days lived in it, while others, like Herman Melville, measure the world by creating new realities from experience married to imagination. The center of the earth finds itself in Ecuador. There, the equator begins and ends its 24,901-mile bulging stretch around the globe. Near Ecuador's capital, Quito, a monument stands marking the point where the equator divides the earth into two halves. One could say this monument created a manmade navel for the earth. A stone tower topped with a globe rises to the sun from this spot. From this earthly navel, four pathways lead in each cardinal direction. From one's position at this manmade center of the earth, any direction may be chosen from which to embark on one's next adventure. A person can stand for a moment in Eternity by placing one foot in the Northern Hemisphere and the other in the Southern Hemisphere. Perhaps for just this purpose, the builders of the monument inlaid a six-inch wide red stone line running east to west. In Ecuador, a person can straddle the world in a single step by riding the serpent that devours its own tail in a stretch around earth. While standing in both halves of the world, a person does not notice the earth spinning one thousand miles per hour. Most people do not often consider the earth's powerful rotation as the harbinger of night and day. The average person straddling the world in Ecuador does not think of the earth revolving around the sun in a circuit lasting about 365 days, or 595 million miles traveled each year at 18.5 miles per second. The movement of the earth seems as imaginary as the equatorial line itself. People do not usually consider themselves voyagers on the great ship Earth, sailing through space at 18.5 miles per second. Most people mark the beginning of existence by their own navels and measure the world only by the circumference of the bodily space they occupy, or by dimensions of experience, of personal joys and sorrows. Some people measure their world only by the number of days lived in it, while others, like Herman Melville, measure the world by creating new realities from experience married to imagination.

In Moby-Dick, Herman Melville creates a world within a world within a world. Melville populates the crew of the Pequod with one of every type of person and sets them to sail on Christmas day, destined never to return to the bosom of the harbor from which they had launched with a cargo hold of hopes and dreams. On board the Pequod, the men battle within themselves, against each other, against the great white whale, against nature, and against God. The world in which the Pequod's men are set adrift may be an imaginary one, but the journey they take is in reality the same for every person. In a world filled with ambiguities, built on imagination, and peopled with constant strife engendered by the ever-present knowledge of the reality of death, the Pequod's journey from cheery launch to mournful finish traces a route that follows the rites of passage each living being endures. In light of the epic proportions of the novel, the vast array of symbology employed by the author to carry out his design, and the mysterious catalogue of meaning drifting within its depths, just how the author managed to keep the novel afloat on a level heading is a question that merits an answer. In Moby-Dick, Melville provides many clues to the literary detective in search of an answer to this question.

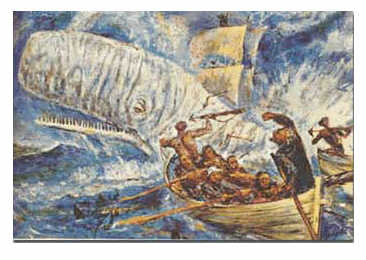

Melville establishes a central rule to his authorial style early in Moby-Dick. "There is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast. Nothing exists in itself..." (Melville 55). Throughout the novel, Melville defines characters and action by contrasting opposites: good against evil, the godly against the godless, the civilized against the uncivilized, the moral against the immoral, and the natural against the artificial. All contrasts directly tie into the central theme of the novel, humanity's search for meaning in the shadow of mortality. In Moby-Dick, mortality is defined by the immortality of the white whale. The action of the novel revolves around the central theme of humanity's yearning and endless search for immortality and the eternal conclusion that confronts the living. Melville suggests through a multitude of contrasts that "nothing exists in itself" including the individual (55). The individual is part of the natural world and must submit to being governed by natural laws; such is the human condition. However, like Ahab, joined with his crew in a mission to destroy Moby-Dick, the individual in union with others is ever on a mission to defy natural law. Just as nothing exists in itself, humanity defines itself by the quality of existence in the external world and the manner in which that world is left behind: humanity defines life by its opposite, death. Melville establishes a central rule to his authorial style early in Moby-Dick. "There is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast. Nothing exists in itself..." (Melville 55). Throughout the novel, Melville defines characters and action by contrasting opposites: good against evil, the godly against the godless, the civilized against the uncivilized, the moral against the immoral, and the natural against the artificial. All contrasts directly tie into the central theme of the novel, humanity's search for meaning in the shadow of mortality. In Moby-Dick, mortality is defined by the immortality of the white whale. The action of the novel revolves around the central theme of humanity's yearning and endless search for immortality and the eternal conclusion that confronts the living. Melville suggests through a multitude of contrasts that "nothing exists in itself" including the individual (55). The individual is part of the natural world and must submit to being governed by natural laws; such is the human condition. However, like Ahab, joined with his crew in a mission to destroy Moby-Dick, the individual in union with others is ever on a mission to defy natural law. Just as nothing exists in itself, humanity defines itself by the quality of existence in the external world and the manner in which that world is left behind: humanity defines life by its opposite, death.

Decades after Melville wrote Moby-Dick, Claude Lévi-Strauss suggested that the mind is a structuring mechanism that imposes form upon whatever it finds at hand (Culler 40). Lévi-Strauss suggested a theory of oppositional reality in which definition is achieved by conceptualizing opposites. Empirical categories serve as conceptual tools, a sort of measuring stick of the mind, for working out abstract notions (Culler 43). This theory is easily recognized in practice in Moby-Dick. For example, Melville takes the opposition of good/evil and explores it in a number of ways including the religious (pious Starbuck contrasted against defiant Ahab), the moral (civilized human being in contrast to cannibal), and the physical (natural light in contrast to the human cost of whale oil).

Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner in The Way We Think suggest a theory of conceptual blending as the means by which humanity thinks. "Identity, integration, and imagination — basic, mysterious, powerful, complex, and mostly unconscious operations — are at the heart of the simplest possible meanings" (xi). In a system of objects, roles, and values, conceptual blending provides the lens that processes and interprets multi-dimensional perceptions. This theory observed in practice occurs in Melville's many characterizations of the white whale, nature, and death in Moby-Dick. Melville was a master of conceptional blending and of creating definitions by oppositional reality. In fact, Melville's veiled characterizations and oppositions make Moby-Dick a challenging, engaging reading experience. So challenging, in fact, that the question of how Melville wove so many images, metaphors, and analogies into an epic whole returns once again.

Melville's use of Ishmael as the narrative voice of Moby-Dick provides another clue to his underlying design. "Ishmael the visionary is often indistinguishable from the mind of the author himself ... the first chapter of Moby-Dick is the statement of a point of view" (Feidelson 31). According to Feidelson, Ishmael is much more than a fictive narrator. Through Ishmael, Melville expounds his personal philosophy and reveals lessons learned from his own unique interior voyage. Ishmael is invisible as a character in action through most of the novel, but his thoughts are the novel. Although this is an apparent violation of narrative standpoint, Feidelson argues that this is a natural consequence of the symbolic method of Moby-Dick (31). "The distinction between the author and his alter ego is submerged in their common function as the voyaging mind" (31). Ishmael's questions and answers concerning life are Melville's questions and answers. Ishmael's clues as to how the novel was written and how the author maintained his focus are Melville's answers to how the novel was written.

Melville, through Ishmael in the following passage, provides another important clue in understanding the author's strategy.

One often hears of writers that rise and swell with their subject, though it may seem but an ordinary one. How, then, with me, writing of this Leviathan? Unconsciously my chirography expands into placard capitals. Give me a condor's quill! Give me Vesuvius' crater for an inkstand! Friends, hold my arms! For in the mere act of penning my thoughts of this Leviathan, they weary me, and make me faint with their out-reaching comprehensiveness of sweep, as if to include the whole circle of the sciences, and all the generations of whales, and men, and mastodons, past, present, and to come, with all the revolving panoramas of empire on earth, and throughout the whole universe, not excluding its suburbs. Such, and so magnifying, is the virtue of a large and liberal theme! We expand to its bulk. To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be who have tried it. (Melville 379)

This paragraph appears in the chapter "The Fossil Whale." Melville may just as well have titled it "The Fossil Book," and written in the pages, "Herein lies the skeleton of this book, Moby-Dick." Every writer begins with an inspiration, the navel of the tale from which the story begins and upon which it centers. Most writers rely on something, sometimes a thing no larger than a flea (for of what material size is an original idea?), to keep the locus of activity upon the original inspiration and to maintain cohesion within the design. This little flea becomes a talisman to which the writer can return to focus the mind upon the task at hand at those times when drifting imagination would supercede authorial purpose. In the twistings and turnings of plot and subplot, the writer finds in the chosen talisman an island in the ocean of mind to be used as a resting spot to restore focus through meditation. The talisman may be a quote or an aphorism under a title, or a prelude, preface, or dedication in the beginning of the process, or a picture of some far away place, idyllic retreat, or catastrophic tragedy. In the case of Moby-Dick, Melville's talisman was a thing a bit larger than a flea, although his sense of humor disguises the importance of the talisman in a humble reference to the flea. Melville did write an enduring novel from a design nearly as small as a flea — the design found on "the white whale's talisman," the gold doubloon nailed by Ahab to the ship's mainmast (Melville 359). Feidelson observed, "the pattern of 'The Doubloon' is the scheme of the book" (32). However, Feidelson fell short of explicating the pattern of the doubloon to prove it as the glue that held the novel together and kept the author focused. The "condor's quill," "Vesuvius's crater," "the whole circle of the sciences," "the revolving panoramas of empire," and the great whale himself can be found on the very coin embedded in the Pequod's mainmast. In fact, the central theme of Moby-Dick can be deciphered from the front and the back, the opposite sides, of this coin. The doubloon is the navel of Moby-Dick and Melville's authorial talisman.

The gold doubloon or "the white whale's talisman" nailed to the mainmast by Ahab and offered as a reward to the first man to spy Moby-Dick is more than a mere pinpoint in relation to the greatness of the Pequod or the men's battle against the elements (Melville 359). The doubloon nailed to the mainmast is the navel of the ship and its nailing there marks the beginnings of the bond that ties the men of the ship together for eternity. The doubloon is more than a symbol of their mission to destroy the unconquerable white whale. Ishmael describes the doubloon as untouchable and immaculate, unpilfered by the ruthless crew as "each sunrise found the doubloon where the sunset left it last" (359). The gold doubloon, writes Ishmael, "was set apart and sanctified to one awe-striking end" (359). Its spot on the mainmast becomes a place where the men walk while meditating on their own objectives, where they huddle in fear during the typhoon, and where they reveal the innermost workings of their minds, hearts, and spirits. The doubloon is a symbol of the attainable, the full potential of humanity, just as the white whale is a symbol of the unattainable that humanity can only poke and jab at but never fully comprehend or capture. The white whale's talisman is the navel of fate, the navel of all things material that humanity makes sacred and holy to assuage the loss of immortality: the only prize humanity truly desires.

In reality, the white whale's talisman is Ecuador's eight-Escudos coin minted from March 14, 1838 until October 30, 1840. 402,649 coins were minted. Most have been melted down or lost and the coin is difficult and expensive to obtain.. 1999 Krause catalog values for the eight-Escudos coin range from $650 to $3500. The specifications for the coin produced in 1838 are the same as for an earlier coin, the four-Escudos, and were issued as an Ecuadorian Executive Decree dated July 14, 1836.

On the obverse side it will have on the entire surface of the coin, and at an elevation corresponding to the sun the zodiac or the ecliptic, perpendicular to the equinoctial line, indicating the equator. Above the sun, and at a proportionate distance, seven stars will be shown, that represent the seven provinces that form the Republic: Quito, Chimborazo, Imbabura, Guayaquil, Manabí, Cuenca and Loja. To the right will be the two principal mountains that make up the Pichincha mountain chain; on the first point the Guagua Pichincha on which will rest a condor and on the second the Ruco Pichincha volcano. To the left of the shield will be engraved a cliff, on it a tower and on this will be placed another condor that will face the one that is on the peak to the right. The inscription will be REPUBLIC OF ECUADOR-QUITO, placed perpendicularly below the sun; and at the right of Quito the initials of the assayer. On the reverse: the bust of Liberty that fills the surface, whose head is girded with a ribbon with the inscription: LIBERTY. On the circumference, it will bear this other: THE POWER IN THE CONSTITUTION. (Ecuador's 8) On the obverse side it will have on the entire surface of the coin, and at an elevation corresponding to the sun the zodiac or the ecliptic, perpendicular to the equinoctial line, indicating the equator. Above the sun, and at a proportionate distance, seven stars will be shown, that represent the seven provinces that form the Republic: Quito, Chimborazo, Imbabura, Guayaquil, Manabí, Cuenca and Loja. To the right will be the two principal mountains that make up the Pichincha mountain chain; on the first point the Guagua Pichincha on which will rest a condor and on the second the Ruco Pichincha volcano. To the left of the shield will be engraved a cliff, on it a tower and on this will be placed another condor that will face the one that is on the peak to the right. The inscription will be REPUBLIC OF ECUADOR-QUITO, placed perpendicularly below the sun; and at the right of Quito the initials of the assayer. On the reverse: the bust of Liberty that fills the surface, whose head is girded with a ribbon with the inscription: LIBERTY. On the circumference, it will bear this other: THE POWER IN THE CONSTITUTION. (Ecuador's 8)

Stamped with "strange figures and inscriptions," the many layers of symbolic meaning found in the images on the coin must be uncovered to reveal its importance to Melville and to verify its purpose as the glue that binds Moby-Dick's complex plotlines and infinite symbology into a complete whole.

To begin to reveal the truth of the doubloon, the first layer explicated reveals its core role in the author's method of design. Through Ishmael as his voice, Melville acknowledges that the novel has assumed epic proportions, "my chirography [penmanship] expands into placard capitals" (Melville 379). The letters on the doubloon are placard capitals in relation to its images. The novel by virtue of its immensity and complexity represents a "placard capital" in the alphabet of books (379). Melville calls for a "condor's quill" and "Vesuvius' crater," the only pen and inkwell of appropriate size for writing a novel of such immense proportion and ambition (379). This marks the single instance in which Melville refers to the type of birds engraved on the doubloon as condors in Moby-Dick. In all other instances, the characters refer to these birds as fowls, cocks, bats, hawks, or crows. The leviathan referred to by Melville in this case is Moby-Dick, whose gaping jaws of death are represented on the doubloon as the two peaks, while the white whale's blowhole is the third peak upon which is found a steaming volcano (379). The great abyss of death and the gaping jaws of the whale are one and the same as symbolized by the valley between the peaks on the coin. The "whole circle of science" is the zodiac sweeping across the top of the coin (379). The "revolving panorama of empire on earth" refers to the words "Republic of Ecuador" encircling the coin's images (379). "Such and so magnifying, is the virtue of a large and liberal theme" brings to mind the magnifying glass needed to explicate the coin, and if the theory holds regarding the importance of the coin to the author, perhaps Melville may have been writing about his own magnifying glass or his magnifying mind. Perhaps the skeptic will be further convinced as more layers are peeled away from this onion of a doubloon. Each image on the white whale's talisman has multiple corresponding meanings in Moby-Dick.

In the talisman's next layer of meaning, the seven main characters each hold a place in the seven stars just above the sun on the doubloon. The center star is Ahab, beside whom the others mass to carry out the mission, "all varieties were welded into oneness, and were all directed to that fatal goal which Ahab their one lord and keel did point to" (Melville 455). Ahab in defiance of nature and of God holds his position above the sun as a human being above the reach of God and fate. The three mates are each represented by placement in the position of honor by a star on Ahab's right, while the three stars to his left represent the harpooners. Each of Ahab's three mates had his choice of harpooners from the three on the crew with the first mate allotted first choice. Starbuck, the pious first mate, chose Queequeg, the noble-hearted cannibal, who placed loyalty among his highest virtues (107). Stubb, the jovial second mate, chose Tashtego, the "hammer," who possessed all the pureblooded strength, seriousness, and respect for nature of the original Native American in his genes (107, 469). Flask, the bullying "mighty mouse" of the Pequod, chose Daggoo, the fear-inspiring blackest of black men (107). In the talisman's next layer of meaning, the seven main characters each hold a place in the seven stars just above the sun on the doubloon. The center star is Ahab, beside whom the others mass to carry out the mission, "all varieties were welded into oneness, and were all directed to that fatal goal which Ahab their one lord and keel did point to" (Melville 455). Ahab in defiance of nature and of God holds his position above the sun as a human being above the reach of God and fate. The three mates are each represented by placement in the position of honor by a star on Ahab's right, while the three stars to his left represent the harpooners. Each of Ahab's three mates had his choice of harpooners from the three on the crew with the first mate allotted first choice. Starbuck, the pious first mate, chose Queequeg, the noble-hearted cannibal, who placed loyalty among his highest virtues (107). Stubb, the jovial second mate, chose Tashtego, the "hammer," who possessed all the pureblooded strength, seriousness, and respect for nature of the original Native American in his genes (107, 469). Flask, the bullying "mighty mouse" of the Pequod, chose Daggoo, the fear-inspiring blackest of black men (107).

Each mate's choice of harpooner balances intelligence with instinct. Together these six men provided the intelligence (mates) and the instinct (harpooners) to the brain (Ahab). Together the seven men represent the qualities necessary for a human being to achieve balance in life. Faith, humor, and bravado (elements of intelligence embodied in Starbuck, Stubb, and Flask respectively) wedded with courage, strength, and fear (elements of instinct embodied in Queequeg, Tashtego, and Dagoo respectively) give birth to all manner of virtue and vice in the pride-driven brain of Ahab, the mastermind behind the mission to chase the mightiest of whales, Moby Dick. Separate, they were just men; together, joined by the navel of the ship, they created a galaxy that represents the human race and the dual nature of humanity in which the ongoing battle between good and evil eternally strives for balance.

Chapter 99, "The Doubloon" describes the talisman and reveals the innermost workings of the main characters. Ahab, the brain of humanity, the "thunder-cloven old oak" of a sea captain, was marked with a scar from "crown to sole" that memorialized an elemental battle with nature (Melville 110). His battle with nature had left his soul burnt to a crisp. Ahab's brittle shell of a soul was stolen along with his leg by the whale, Moby-Dick — God's messenger (111). Ahab defiantly places himself and the other six stars above God, above fate, and above the sun by his unquenchable need for vengeance and his inability to forgive God for allowing him to live as an incomplete being, destined to suffer from despair and dread.

Ahab, often interpreted as a godless human being, is in reality angry with the god in whom he believes but no longer trusts. Ahab represents the type of thunderstruck, defiant being driven by a vengeance that nothing, not even God, could stand in the path of without bearing witness to the power of betrayal at work upon the living. Ahab embodies the human despair and dread that occurs in those who realize that a "loving God" has cursed them with a living knowledge of unavoidable death. Ahab has no trust in a god whose "mowers" daily strike down the living (Melville 445). Instead, he places his trust in the Egyptian magician Fedallah, a pagan prophet whose mission is to keep Ahab alive, in spite of natural law, through magic rather than faith. Ahab finds his hope in Fedallah, and not in the promise of God's salvation. Ahab's pagan belief in Fedallah is a subliminal characteristic of Ahab's that surfaces in the reader's consciousness as "evil." Ahab believes his soul and his faith will be resurrected only if he kills the white whale that had deprived him of his material and spiritual dignity, his leg and his soul. Even though magic rather than faith is Ahab's weapon of choice, he firmly believes God's will for him is to destroy Moby-Dick (445). Ahab tries to justify his need for vengeance to Starbuck and in the process reveals his secret cause, the will of God. Ahab, often interpreted as a godless human being, is in reality angry with the god in whom he believes but no longer trusts. Ahab represents the type of thunderstruck, defiant being driven by a vengeance that nothing, not even God, could stand in the path of without bearing witness to the power of betrayal at work upon the living. Ahab embodies the human despair and dread that occurs in those who realize that a "loving God" has cursed them with a living knowledge of unavoidable death. Ahab has no trust in a god whose "mowers" daily strike down the living (Melville 445). Instead, he places his trust in the Egyptian magician Fedallah, a pagan prophet whose mission is to keep Ahab alive, in spite of natural law, through magic rather than faith. Ahab finds his hope in Fedallah, and not in the promise of God's salvation. Ahab's pagan belief in Fedallah is a subliminal characteristic of Ahab's that surfaces in the reader's consciousness as "evil." Ahab believes his soul and his faith will be resurrected only if he kills the white whale that had deprived him of his material and spiritual dignity, his leg and his soul. Even though magic rather than faith is Ahab's weapon of choice, he firmly believes God's will for him is to destroy Moby-Dick (445). Ahab tries to justify his need for vengeance to Starbuck and in the process reveals his secret cause, the will of God.

Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike. And all the time, lo! that smiling sky, and this unsounded sea! Look! see yon Albicore! Who put it into him to chase and fang that flying-fish? Where do murderers go, man! Who's to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar? But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay. Sleeping? Aye, toil we how we may, we all sleep at last on the field. Sleep? Aye, and rust amid greenness; as last year's scythes flung down, and left in the half-cut swaths-Starbuck? (Melville 445)

Starbuck, however, is gone; for to his ears Ahab's words are a blasphemous condemnation of God as an unjust creator who destroys a bit of godhead with each death on earth. The doubloon re-appears in Ahab's condemnation of God in the pleasant image of the "Albicore" and the new-mown hay on an Andes mountainside, a tableau that turns bleak with realization of its true intent — the mowing down of men by a God who refuses to share the gift of immortality with humanity. Ahab is a person at war against himself and his god. Ahab cannot justify his own existence of suffering and pain against death as the promised end of his toil. He sees his mission against Moby-Dick as one of God's own making, of God's will for him and for the whale. He must prove that the God he has been taught to believe in is just, and that particular type of justness can only be proven by the whale's death at Ahab's hand. For how else could God be proven just? Not as a God who keeps for himself the best of all things, immortality, and yet allows humanity to suffer a physical existence filled with suffering rewarded by death. If Jonah was allowed to escape the whale by God's grace, then Ahab, too, believes God wills his cause. Ahab's God could only be proven just by a return of immortality to humanity. Ahab's war on the whale is a war against mortality and against God and for God.

Ahab's interpretation of the gold doubloon bears witness to his vision of God as an unjust creator who proves false to his own creation, humanity. Gazing upon the doubloon, Ahab sees "something egotistical in mountain-tops and towers, and all other grand and lofty things," as he imagines the doubloon to represent himself (Melville 359). "Three peaks, proud as Lucifer. The firm tower, that is Ahab; the volcano, that is Ahab; the courageous, the undaunted, and victorious fowl, that, too, is Ahab; all are Ahab" (359). In the coin, Ahab sees the roundness of the globe "like a magician's glass, a mirror to each man of his own mysterious self" (359). In the mirror of the doubloon, Ahab realizes that the powers of God cannot solve human problems; humanity must resolve its own ambiguities (359-360). To Ahab, the zodiac symbols around the sun are signs of future storms and past storms (359-360). Ahab sees these signs as evidence of eternal human suffering unheeded by God "Born in throes, 'tis fit that man should live in pains and die in pangs!" (360). To Ahab, man is "stout stuff" capable of handling the woes of the world without God's help (360). As he moves away from the ship's navel, Starbuck approaches. Ahab's interpretation of the gold doubloon bears witness to his vision of God as an unjust creator who proves false to his own creation, humanity. Gazing upon the doubloon, Ahab sees "something egotistical in mountain-tops and towers, and all other grand and lofty things," as he imagines the doubloon to represent himself (Melville 359). "Three peaks, proud as Lucifer. The firm tower, that is Ahab; the volcano, that is Ahab; the courageous, the undaunted, and victorious fowl, that, too, is Ahab; all are Ahab" (359). In the coin, Ahab sees the roundness of the globe "like a magician's glass, a mirror to each man of his own mysterious self" (359). In the mirror of the doubloon, Ahab realizes that the powers of God cannot solve human problems; humanity must resolve its own ambiguities (359-360). To Ahab, the zodiac symbols around the sun are signs of future storms and past storms (359-360). Ahab sees these signs as evidence of eternal human suffering unheeded by God "Born in throes, 'tis fit that man should live in pains and die in pangs!" (360). To Ahab, man is "stout stuff" capable of handling the woes of the world without God's help (360). As he moves away from the ship's navel, Starbuck approaches.

Starbuck, a man imbued with the optimism of the faithful, a man with flesh as hard as a "twice-baked biscuit" and of "live blood" that "would not spoil like bottled ale" represents all those of sacred flesh and blood who carry the body of Christ within as a memory of self-sacrifice (102). Starbuck's piety and faith lead him down every path of dissuasion to the course of Captain Ahab (Melville 102). Starbuck's type would "endure for long ages to come" and "endure always" in the spirits of those beings that deign to live by the Golden Rule (103). Starbuck embodies the being that willingly and faithfully treads the path of self-sacrifice to salvation as laid out by Christ, and who lives with an acceptance of fate neither expecting nor taking more from life than opportunity provides.

"I will have no man in my boat," said Starbuck, "who is not afraid of the whale" (Melville 103). Nor would Starbuck tolerate anyone who did not fear God's wrath. Even Queequeg, through his worship of Yojo, showed respect for a higher than human power. In fact, Queequeg's loyalty to his god provided a much-needed counter-balance for Starbuck's faith. Starbuck, though pious, built his religious foundation on truths that he often calls into question when faced with insurmountable odds. For Starbuck, courage was a useful thing like his harpooner, Queequeg, and not a sentiment; courage was a staple like bread and meat packed in the souls of all aboard the Pequod (103). Starbuck sailed to make a living, and not to chase revenge for the living clause; a clause made by Nature that all things gifted with life must die. The unfathomable deep had swallowed Starbuck's father and brother, and he was in no hurry to join them (104). In spite of his memories and his superstitions, piety and faith flourished in Starbuck, a faith that arose from belief in an absolute God that offers a safe harbor at journey's end (104). Starbuck sees a different reflection than Ahab in the mirror of the doubloon.

Starbuck, ever the faithful optimist, reads the doubloon with pagan superstition as a symbol of religious hope and salvation. "Fairy fingers" had not touched the doubloon before Starbuck, but Ahab's "devil's claws" had preceded him (Melville 360). Starbuck reads "Belshazzar's awful writing" and finds the valley of the shadow of death in "a dark valley between three mighty, heavenly peaks" (360). Between those peaks, he sees the gaping abyss of promised death, but Starbuck looks to higher laws and also sees "the Trinity" in the promised land of those Andes peaks (360). "In this vale of Death, God girds us round; and over all our gloom, the sun of Righteousness still shines a beacon and a hope" (360). To Starbuck's way of thinking, if one chooses to look down relying upon earthly means, one loses hope; if one looks up relying on higher laws, one gains hope enough to continue the voyage of life (360). Somehow, in spite of his faithful optimism, a bit of Ahab's fear and dread creeps into Starbuck's reality. For Starbuck a tiny moment of truth dawns as he realizes the sun on the doubloon is no fixture in reality, but is constantly on the move; night eternally falls; no solace can be found for his dread as he realizes he gazes in vain for a god that lives only in human imagination (360). He quits the navel of the ship "lest Truth shake me falsely," a subtle reminder of the ambiguity of human existence (360). Starbuck, ever the faithful optimist, reads the doubloon with pagan superstition as a symbol of religious hope and salvation. "Fairy fingers" had not touched the doubloon before Starbuck, but Ahab's "devil's claws" had preceded him (Melville 360). Starbuck reads "Belshazzar's awful writing" and finds the valley of the shadow of death in "a dark valley between three mighty, heavenly peaks" (360). Between those peaks, he sees the gaping abyss of promised death, but Starbuck looks to higher laws and also sees "the Trinity" in the promised land of those Andes peaks (360). "In this vale of Death, God girds us round; and over all our gloom, the sun of Righteousness still shines a beacon and a hope" (360). To Starbuck's way of thinking, if one chooses to look down relying upon earthly means, one loses hope; if one looks up relying on higher laws, one gains hope enough to continue the voyage of life (360). Somehow, in spite of his faithful optimism, a bit of Ahab's fear and dread creeps into Starbuck's reality. For Starbuck a tiny moment of truth dawns as he realizes the sun on the doubloon is no fixture in reality, but is constantly on the move; night eternally falls; no solace can be found for his dread as he realizes he gazes in vain for a god that lives only in human imagination (360). He quits the navel of the ship "lest Truth shake me falsely," a subtle reminder of the ambiguity of human existence (360).

Stubb approaches the mainmast after Starbuck, and at first decides interpreting the doubloon is an uneconomical use of time. Stubb, the second mate, represents the happy-go-lucky being without a care in the world that lives in a state of denial concerning its own nature and the nature of all things (Melville 105). Stubb's humor is the mother of the bliss of denial. Everything is funny to Stubb and nothing in life, including death, is to be taken seriously. "Long usage, had for this Stubb, converted the jaws of death into an easy chair" (105). Tashtego, as Stubb's counter-balance, provides the serious respect for life and nature Stubb lacks. Tashtego, a Native American "unmixed Indian from Gay Head," is "the last remnant of a village of red men" now absorbed into a white world, a world as white as the great whale itself (107). In Tashtego, the Starbucks of the world see a "wild Indian" and "a son of the Prince of the Powers of the Air"; the Ahabs of the world find in Tashtego a fellow traveler (107).

Stubb's type is "neither craven nor valiant," but takes "perils as they come with an indifferent air," "toiling away" when need be and "calm and collected" as can be only a being that believes in human natural right to dominion over nature (Melville 105). Death, if Stubbs thought of it all, was something he would find out about when "he obeyed the order, and not sooner" (105). Stubb's type of being cheerily trudges off with "the burden of life in a world full of grave peddlers" (105). Stubb's type is entranced with the distraction of material things, always puffing away on a pipe, meeting the demands of the body and unconcerned with spiritual needs. Stubb's constant tobacco smoke acts as a sort of disinfectant for mortality by sweeping away or hiding in a misty mirage the "nameless miseries of the numberless mortals who have died exhaling" earthly air (106). Stubb silently observed Ahab and Starbuck meditating on the talisman of the white whale. He watches them move away from the mainmast with faces "nine fathoms long," then moves up to deliver his interpretation (360).

Stubb would just as soon spend the doubloon as look at it since it looks very queer to him (Melville 360). He had seen many doubloons in his travels, but this one was wonderful (360). "Signs and wonders" were reflected back to him from the mirror of the talisman (360). He decides to use an almanac to raise "a meaning" out of the zodiac symbols (360). He sees Aries, the Ram; Taurus, the Bull; Gemini, the Twins; and notices "the sun wheels among them" on the talisman "crossing the threshold between two of twelve sitting rooms all in a ring" (360). With surprising clarity, Stubb sees "the life of man in one round chapter" in the zodiac (361).

According to Stubb, the Ram begets us; the Bull bumps us; the Twins, virtue and vice, one is sought, the other avoided; the Crab drags us back to vice; the Lion bites and scratches; we meet the Virgin, fall in love, and think we are happy for a moment (Melville 361). Then, the Scales are tipped and happiness is found wanting (361). While we are very sad about that, we jump as the Scorpion stings us in the rear (361). While curing the wound, the Archer amuses himself by stinging us more (361). As we pluck out his shafts, the Goat tosses us about (361). Then the Water Bearer pours out his deluge and drowns us, following which we wind up with the Fishes, asleep (361). Only the sun goes through it every year and comes out alive and hearty (361). "Jollily he, aloft there, wheels through toil and trouble; and so, allow here, does jolly Stubb" (361). After this bit of surprising philosophizing on the part of Stubb, he bids the doubloon adieu and quickly hides as he sees Flask approach.

Flask, the third mate, represents the type of being that bullies its way through life with the bravado of the Chosen. Flask, called King-Post for his diminutive size combined with a stubborn immoveable will, made it a point of honor to destroy those things such as whales, which he believed "personally and hereditarily affronted him" by their very existence (Melville 106). Flask's type feels neither reverence for the majestic, nor apprehension of danger in encountering things of bigger bulk (106). In Flask's view, the "wondrous whale was but a species of magnified mouse ... or water-rat" to be "killed and boiled" (106). Flask's harpooner, Daggoo, "a gigantic, coal-black negro-savage, with a lion-like tread," represents the noble wildness of nature concealed by servitude to humanity's higher laws (107). Next to Daggoo's barbaric virtues and six feet five inch height, little Flask looked like a "chess-man beside him" (108). As counter-balance to Flask's bravado and materialistic leanings, Daggoo strikes the blackest fear into those mortals and other creatures of land and sea that might otherwise assume Flask's bark to be worse than his bite. Flask, the third mate, represents the type of being that bullies its way through life with the bravado of the Chosen. Flask, called King-Post for his diminutive size combined with a stubborn immoveable will, made it a point of honor to destroy those things such as whales, which he believed "personally and hereditarily affronted him" by their very existence (Melville 106). Flask's type feels neither reverence for the majestic, nor apprehension of danger in encountering things of bigger bulk (106). In Flask's view, the "wondrous whale was but a species of magnified mouse ... or water-rat" to be "killed and boiled" (106). Flask's harpooner, Daggoo, "a gigantic, coal-black negro-savage, with a lion-like tread," represents the noble wildness of nature concealed by servitude to humanity's higher laws (107). Next to Daggoo's barbaric virtues and six feet five inch height, little Flask looked like a "chess-man beside him" (108). As counter-balance to Flask's bravado and materialistic leanings, Daggoo strikes the blackest fear into those mortals and other creatures of land and sea that might otherwise assume Flask's bark to be worse than his bite.

Peering at the doubloon, Flask sees only gold in the white whale's talisman. Flask's type believes in human ingenuity as the only necessary tool for overcoming nature's obstacles; obstacles placed before him for the sole purpose of being overcome. He sees nature as utilitarian, a means to his ends. He finds nothing superstitious or significant reflected back upon him from the coin. To Flask, the doubloon is nothing more than a "round thing made of gold," "worth sixteen dollars," and that means, "at two cents a cigar," "nine hundred and sixty cigars" (Melville 361).

Stubb continues to spy at the ship's navel as other crewmembers approach. The Manxman, the oldest soul aboard the Pequod and one of Tashtego's ancestors, approaches, while from his hiding place Stubb notices a horseshoe nailed to the back of the mainmast (Melville 362). The Manxman also sees it, and to him the horseshoe sign opposite the coin is a sign of "the roaring and devouring lion" and seeing it causes him to fear for the safety of the Pequod that he believes is fated by the signs to encounter the white whale when the sun stands in the sign of the lion, thus spelling disaster for all aboard (362). Queequeg approaches and Stubb reckons the cannibal's tattooing as mysterious as the signs of the zodiac (362). Stubb watches as Queequeg compares the images on his thigh to those on the talisman. Stubb assumes the talisman means nothing more to the cannibal than "an old button off some king's trowsers" (362). The "ghost-devil" Fedallah approaches with his "tail coiled out of sight," makes a sign, and bows before the talisman (362). Stubb sees Fedallah reflected back from the doubloon as a "fire worshipper" of the sun emblazoned on the coin (362). Stubb sees pitiful Pip, who lost his mind and his soul as he bobbed upon the waves — taken for lost, and bodily (but not mentally) recovered from the depths — approach the talisman. Stubb listens intently as the Pequod's little prophet interprets the talisman's meaning as a warning foreshadowing Ahab's fate.

I look, you look, he looks; we look, ye look, they look.... And I, you, and he; and we, ye, and they, are all bats; and I'm a crow, especially when I stand a'top of this pine tree here. Caw! caw! caw! caw! caw! caw! Ain't I a crow? And where's the scare-crow? There he stands; two bones stuck into a pair of old trowsers, and two more poked into the sleeves of an old jacket.

Here's the ship's navel, this doubloon here, and they are all on fire to unscrew it. But, unscrew your navel, and what's the consequence? Then again, if it stays here, that is ugly, too, for when aught's nailed to the mast it's a sign that things grow desperate. Ha, ha! old Ahab! the White Whale; he'll nail ye! This is a pine tree. My father, in old Tolland county, cut down a pine tree once, and found a silver ring grown over in it; some old darkey's wedding ring. How did it get there? And so they'll say in the resurrection, when they come to fish up this old mast, and find a doubloon lodged in it, with bedded oysters for the shaggy bark. Oh, the gold! the precious, precious gold! - the green miser 'll hoard ye soon! Hish! hish! God goes 'mong the worlds blackberrying. Cook! ho, cook! and cook us! Jenny! hey, hey, hey, hey, hey, Jenny, Jenny! and get your hoe-cake done!" (Melville 362-363)

Pip foresees the great abyss of death awaiting the Pequod in the jaws of the white whale reflected in the doubloon. He also steers the course toward unraveling the next layer of meaning hidden in the white whale's talisman. Pip sees the crew as "bats," while he sees himself as a crow sitting in a pine tree (Melville 362). In reality, the "pine tree" is the mainmast. The masts of whaling ships were often hewn from whole white pines, as are power poles today. The three Andes peaks on the coin represent not only the gaping abyss of the white whale's jaws, but the Pequod itself. Each of the peaks represents a mast and the tower a crow's nest topped with a condor (bat/man). In perspective to the actual outlay of a 17th century whaling ship, the mainmast is the center Andes peak topped with a banner (the second condor), while the third Andes peak topped with a volcano represents the try-works to be found abaft the foremast (Putnam 509, 511). The first peak represents the mizzenmast and its tower represents the deckhouse and captain's cabin found aft of the mizzenmast (509). The images of the talisman symbolize The Pequod as the jaws of death in the form of a battleship designed to fight nature and kill whales, just as those same peaks symbolize the white whale himself.

In defining the three peaks of the Andes as representing the masts of the ship, another layer of the talisman's meaning is unveiled. The sun sails high overhead the peaks, masts, or jaws, and transcends the zodiacal ring that represents the cycle of humanity. The great abyss of death eternally awaits its bounty. The same laws of nature bind the two — life and death, human and whale, human and nature — in an eternal marriage in both nature's and the coin's tableau. The sun looks down upon humanity and nature, while bestowing life but never restoring life once lost, only renewing it in a newborn vehicle. "In vain, oh whale, dost thou seek intercedings with yon all-quickening sun, that only calls forth life, but gives it not again" (409).

Through the lacings of the leaves, the great sun seemed a flying shuttle weaving the unwearied verdure. Oh, busy weaver! unseen weaver! - pause! - one word! - whither flows the fabric? what palace may it deck? wherefore all these ceaseless toilings? Speak, weaver! — stay thy hand! — but one single word with thee! Nay - the shuttle flies —the figures float from forth the loom; the freshet — rushing carpet forever slides away. The weaver-god, he weaves; and by that weaving is he deafened, that he hears no mortal voice; and by that humming, we, too, who look on the loom are deafened; and only when we escape it shall we hear the thousand voices that speak through it. For even so it is in all material factories. The spoken words that are inaudible among the flying spindles; those same words are plainly heard without the walls, bursting from the opened casements. Thereby have villanies been detected. Ah, mortal! then, be heedful; for so, in all this din of the great world's loom, thy subtlest thinkings may be overheard afar. (Melville 374-375)

In equatorial zones, the seasons never change. The Inca Indians, whose ancestors still people the Andes' slopes, worshipped the sun. The sun emblazoned on the talisman represents the ever-watching eye of God, the weaver of fates, a god that never sways from the goodness of giving and taking life, one that never tires of bestowing just rewards. The passing of those mastodons and realms of men from antiquity to the present are all observed by the doubloon's watchful eye of Fate, whose glance forever shines upon humanity a promise of the abyss of death.

In this freshly uncovered layer of meaning, the battle between humanity and nature is revealed in the white whale's talisman. The tower represents economic, cultural, political, and religious institutions. On the opposite peak stands nature, the condor, forever opposing humanity, which perceives nature as always being in need of refining and controlling in order to ensure human survival. The lines of the battlefield are drawn in their entirety on the third peak, where stands nature's weapon, the volcano, the symbol of fire, earthquake, typhoon and all other weapons in nature's infernal arsenal beyond human manipulation.

Digging a bit deeper into this layer, the battle between humanity and nature becomes one between good and evil. The human physicality is represented by the tower and human spirit by the condor on the highest peak, while the purifying fire of the volcano represents the spark of life granted but once in a lifetime, the spark that binds the material to the spiritual on the earthly plane. Going a bit deeper, the tower represents all that humanity defines as good (physical life) while the paired peaks represent all that is wild (spiritual life without body), or the evil of the world accompanied by the fires of hell. Shining down upon the battlefield of life is the eternal sun opposite the jaws of the unconquerable white whale, death. The white whale's talisman is a microcosmic representation of the eternal battle waged by humanity against death. Is crossing the abyss to the peak of spiritual life after death a human instinct or merely an imprinted desire, nature or nurture? The talisman symbolizes the eternal marriage of good and evil, what human wisdom identifies as life giving (good) and life taking (evil). The talisman's beauty and desirability is bound in its representation of the eternal passage of time found in the zodiacal inscription. The human being forever dreams of immortality as "against the wind he now steers for the open jaw," until the final breath is drawn and the waiting jaws sated (Melville 461).

Recreating the tableau on the white whale's talisman, Ahab spies Moby-Dick from his spot on the Main Royal Masthead, between the main-top-sail and the top-gallant-sail in the center of the ship as Tashtego watches from just beneath on the cap of the top-gallant-mast (Melville 446). Together they peer into the great abyss, two condors on their mountain perches. Ahab plucks and grabs at the claws of fate with his every breath. "The doubloon is mine, Fate reserved the doubloon for me" he argues with Tashtego upon sighting the white whale (Melville 446). Reconsidering his covetousness, Ahab decides to leave the doubloon nailed to the mainmast, for although the gold is his, he "shall let it abide here till the White Whale is dead" (453). Only when his soul is restored to virgin immortality will Ahab allow the doubloon to be dismasted. The Pequod's is an eternal voyage that replicates humanity's struggle with the concept of eternity. Ahab, joined with his stars, is every human being. Ahab promises a king's ransom in gold to the listening crew, and one cannot help but think of a promised land with streets paved in gold.

Heaven, though, has other plans for the crew of the Pequod. A marauding hawk steals Ahab's hat as from her arsenal across the abyss, Nature reaches out a warning hand, and though Starbuck would listen, Ahab fails to heed the warning. By the third day of the chase, Moby-Dick has escaped the grasp of Ahab and taken a mighty toll. Fedallah is missing, Ahab has gone through two additional artificial limbs, the ship's crew is shaken, and the small boats have all been nearly destroyed. One cannot help but think of the coral labyrinth awaiting the crew in the milky depths of the white whale's dominion.

As the third day dawns, Ahab sees life as "a lovely day again; were it a new-made world, and made for a summer-house to the angels, and this morning the first of its throwing open to them, a fairer day could not dawn upon that world" (Melville 460). Ahab remakes the tower of the talisman as a summerhouse for angels in a newborn, perfect world. By noon, Ahab is sorely disappointed as "the doubloon goes a-begging" (461). Finally, with the white whale spotted, Ahab goes forth to meet his adversary. A hawk sweeps down to steal the red flag of Ahab from the mainmast. Except for Ahab's boat, the remaining small boats are destroyed by Moby-Dick and the crews return to the Pequod. Hammers pound all around as heartbeats drumming last-gasp life back into the beaten boats. The three harpooners climb the masts re-enacting the tableau of the talisman. Tashtego, climbs down and then up again with hammer, nails, and flag in hand, to restore the dismasted spirit of the Pequod. Moby-Dick turns against the ship, and before Ahab's eyes, smites the ship in two with his bulldozing forehead and gaping jaw.

Tashtego's hammer "remained suspended in his hand" while the red flame of flag wraps itself about him (467). Starbuck calls on God, Stubb verbally thumbs his nose at the white whale, and Flask hopes his mother has drawn his pay (467). Spreading a broad band of "semi-circular foam" (recalling the zodiac on the coin before the abyss of death, the mountain range and the whale's gaping jaw), Moby-Dick shatters the tower of a ship, the unnatural thing that so annoyed him with its presence.

Ahab continues to defy God and Fate to his last breath.

I turn my body from the sun. What ho, Tashtego! Let me hear thy hammer. Oh! ye three unsurrendered spires of mine; thou uncracked keel; and only god-bullied hull; thou firm deck, and haughty helm, and Pole-pointed prow, — death-glorious ship! must ye then perish, and without me? Am I cut off from the last fond pride of meanest shipwrecked captains? Oh, lonely death on lonely life! Oh, now I feel my topmost greatness lies in my topmost grief. Ho, ho! from all your furthest bounds, pour ye now in, ye bold billows of my whole foregone life, and top this one piled comber of my death! Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell's heart I stab at thee; for hate's sake I spit my last breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool! and since neither can be mine, let me then tow to pieces, while still chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale! Thus, I give up the spear! (Melville 468)

Casting his harpoon at Moby-Dick, Ahab finds his own noose, and the Pequod sinks with all aboard save one. Tashtego's hand, with hammer and flag held tight, rises from the water in defiance and nails the flag of Ahab with a hawk to the mainmast. The tableau of the doubloon now completed, the crew goes to rest "upon a mattress all too soft" (Melville 467).

The pages of Moby-Dick are profusely littered with references to the doubloon's symbolic meaning, but all signs lead back to the ambiguous nature of life lived in the shadow of death, the defining principle of the human condition. The eternal marriage of good and evil found in nature and in human beings is represented in every major action outlined in the novel. By whichever manner — Ahab's, Starbuck's, Stubb's, Flask's, or Tashtego's — that the reader chooses to approach the dread that arises with the knowledge of death, no matter; the end result is the same for the individual as it was for the Pequod. The body is as a "storm-tossed ship that miserably drives along the leeward land" (Melville 97). The imagined "port" is safety, home, a warm hearth, and "all that's kind to our mortalities" (97). But to the soul, to the spirit of the ship, the land is the "direst jeopardy" (97). "With all her might she crowds all sail off shore; in so doing, fights 'ginst the very winds that fain would blow her homeward; seeks all the lashed sea's landlessness again for refuge's sake forlornly rushing into peril; her only friend her bitterest foe" (97). According to Melville, the soul seeks the sheltering abyss of material death. Dread is recognition of "that mortally intolerable truth; that all deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort of the soul to keep the open independence of her sea; while the wildest winds of heaven and earth conspire to cast her on the treacherous, slavish shore," imprisoned in the tower of the human body, fated to look forever with anguish upon the gaping abyss of death (97).

Wedded in death in the abyss of the coral labyrinth following the destruction of the Pequod by Moby-Dick, the crew, joined by the navel — the talisman of the white whale — lay wrapped in each other's arms and legs, together a "counterpane" of all who walk the earth, and must someday leave its bright sunny promise by the eternal vow between life and death and day and night (Melville 32). So too it was for Ishmael as he lay with Queequeg under the counterpane of their shared bed, in a state between asleep and awake enshrouded in a mystery that mimics the "bride-groom clasp of death" (33).

"At last I must have fallen into a troubled nightmare of a doze; and slowly waking from it — half steeped in dreams — I opened my eyes, and the before sunlit room was now wrapped in outer darkness. Instantly I felt a shock running through all my frame; nothing was to be seen, and nothing was to be heard; but a supernatural hand seemed placed in mine. My arm hung over the counterpane, and the nameless, unimaginable, silent form or phantom, to which the hand belonged, seemed closely seated by my bed-side. For what seemed ages piled on ages, I lay there, frozen with the most awful fears, not daring to drag away my hand; yet ever thinking that if I could but stir it one single inch, the horrid spell would be broken. (Melville 33)

So it is that human beings ever dream of escape from the cold embrace of death. But the dark rest of death's embrace is as necessary to human contentment as is the light of life, for "no man can ever feel his own identity aright except his eyes be closed; as if darkness were indeed the proper element of our essences, though light be more congenial to our clayey part" (Melville 55). In the absence of light, no shadows fall, no stars glimmer, no new day comes. In the presence of light beauty prevails and the world comes alive. As the human lifespan ends, our bodies dress our souls like a nightgown. Like Ahab and Ishmael, we dream of unlocking death's "bridegroom clasp" (33). Like Ahab, some choose to live in vengeance with every drawn breath. Others commandeer the faith of Starbuck, the humor of Stubb, or the bravado of Flask to face each new day. Each day the sun rises with promise, and with waking, the material world breaks anew upon the reverie of the soul. And yet, knowledge of rest encourages the life lived day by day: "Oh, Ahab! what shall be grand in thee, it must needs be plucked at from the skies, and dived for in the deep, and featured in the unbodied air!" (130).

Death is only a launching into the region of the strange Untried; it is but the first salutation to the possibilities of the immense Remote, the Wild, the Watery, the Unshored; therefore, to the death-longing eyes of such men, who still have left in them some interior compunctions against suicide, does the all-contributed and all- receptive ocean alluringly spread forth his whole plain of unimaginable, taking terrors, and wonderful, new-life adventures; and from the hearts of infinite Pacifics, the thousand mermaids sing to them - Come hither, broken-hearted; here is another life without the guilt of intermediate death; here are wonders supernatural, without dying for them. Come hither! bury thyself in a life which, to your now equally abhorred and abhorring, landed world, is more oblivious than death. Come hither! put up thy grave-stone, too, within the churchyard, and come hither, till we marry thee! (Melville 402)

Married to the obverse side, the reverse side of the talisman of the white whale carries a bust of Liberty with a single word emblazoned on her headband — Liberty (Ecuador's 8). Certainly, Ahab knew the secret on the reverse side of the coin, and perhaps this is the reason he left the navel in place after he had reclaimed it. For had the men known that their binding cause would cost them the liberty of life, the mission would surely have ended sooner. The reverse side of the coin bears the inscription "THE POWER IN THE CONSTITUTION" around its circumference (Ecuador's 8). Herein lies another of Melville's clues, for he saw in the doubloon's reverse side the power of the human being. Melville saw in the human constitution the power to become the liberator of the spirit, to overcome adversity, to find hope in the smallest or the largest of things, a thought, a flea, a coin, a hammer, or a whale — without the trappings of religiosity. The chase after immortality, a life lived every moment in vengeance is not for those, like Melville, who define their existences by the reverse side of the talisman. "For what are the comprehensible terrors of man compared with the interlinked terrors and wonders of God" (Melville 99)? In the reverse side of the talisman, Melville does not see death as an ending; he sees it as a liberating beginning, a becoming in the next stage of spiritual voyaging. To Melville, death is merely another rite of passage for being; at death, the spirit finds its homeport once again, be it in an imagined coral labyrinth or a promised land with streets of gold. To Melville, the great abyss of the whale's jaw was the beckoning gateway to a new voyage, and represented a coming-to of the spirit rather than a going-away of the body. Still, that homeport can only be imagined and, even so, never fully captured by human imagination or comprehended by human consciousness. Like the great whale himself, the other side of life that lies through the gateway of the great abyss will always remain a mystery.

Melville's philosophy of life and death threads its way through the pages of Moby-Dick. Melville sought to share his philosophy with others, to paint a world of promise for those beings he understood to suffer from the same ambiguities of life as Ahab, Starbuck, Stubb, Flask, and the others aboard the Pequod. "Here it be said that this pertinacious pursuit of one particular whale, continued through day into night, and night into day, is a thing by no means unprecedented..." (Melville 453). Nor is it a thing unprecedented in today's world. Melville knew each individual chases a white whale of one form or another. Each person is a potential Ahab. Melville wanted us not to forget that when we stand in the center of our individual worlds, we choose the paths we follow regardless of whom or what we blame for the consequences. Each individual chooses his own path, writes his own story, and paints his own world. Whichever direction one voyages from the center of one's own world — north, south, east, or west — every thought is an unrealized empire of immeasurable potential awaiting realization.

A whale ship was Ishmael's "Yale College" and his "Harvard" (Melville 101). Melville himself spent several years on whaling ships (Baym 2256). It is quite possible that he came into possession of the Ecuadorian eight-Escudos coin on such a voyage. One can imagine him in a cabin below decks, drifting with the sea, fingering the coin while dreaming the tale that would unfold in later years as Moby-Dick. The evidence for such a conjecture can be found in nearly every chapter of the novel. Reading Moby-Dick with the white whale's talisman foremost in one's mind, it is an easy mental exercise to imagine Melville at his desk with the golden talisman in a prominent place. When his mind began to drift with the complexities of the novel, his eyes could easily return to the island of the coin, a world within a world within in a world that forever evolves into another world, "a draught, nay, but the draught of a draught" (Melville 128).

But here is an artist. He desires to paint you the dreamiest, shadiest, quietest, most enchanting bit of romantic landscape in all the valley of the Saco. What is the chief element he employs? There stand his trees, each with a hollow trunk, as if a hermit and a crucifix were within; and here sleeps his meadow, and there sleep his cattle; and up from yonder cottage goes a sleepy smoke. Deep into distant woodlands winds a mazy way, reaching to overlapping spurs of mountains bathed in their hill-side blue. But though the picture lies thus tranced, and though this pine-tree shakes down its sighs like leaves upon this shepherd's head, yet all were vain, unless the shepherd's eye were fixed upon the magic stream before him. (Melville 13)

Work cited

- Baym, Nina, Ed. "Herman Melville." The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Vol. 1. 5th ed. New York: Norton, 1998.

- Culler, Jonathan. Structuralist Poetics. New York: Cornell University Press, 1975.

- Ecuador's 8. Retrieved 11 November 2002 from http://www.ecuadornumismatics.com

- Fauconnier, G. and Turner, M. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

- Fairbridge, Rhodes, W. "Earth." Collier's Encyclopedia. Ed. William D. Halsey. Vol. 8 of 24 vols. New York: Collier, 1980.

- Feidelson, Charles Jr. Symbolism and American Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.

- Geography Online. Retrieved 11 November 2002 from http://geography.miningco.com

- Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. Eds. Harrison Hayford & Hershel Parker. New York: Norton, 1967.

- Putnam, John B. "Whaling and Whalecraft: A Pictorial Account." Moby Dick. Eds. Harrison Hayford & Hershel Parker. New York: Norton, 1967.

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|