|

Mysticism: The Craft of Love

© 2007 Wilhelm Oosthuizen, used by permission

[Images: "Evelyn Underhill's Icon" by Suzanne Schleck]

In The Hero's Journey (2003), in reference to his book, The Inner Reaches of Outer Space (2002), Joseph Campbell intimates: In The Hero's Journey (2003), in reference to his book, The Inner Reaches of Outer Space (2002), Joseph Campbell intimates:

...the last chapter, the one I regard as the culminating one in the book, was inspired by a remark from my wife, Jean. One day when we were talking about things like this she said, "The way of the mystic and the way of the artist are very much alike, except that the mystic doesn't have the craft." I use that as the key here for paralleling the two ways of the mystical life and the artist's life. The artist with a craft remains in touch with the world; the mystic can spin off and lose touch and frequently does. And so it seems to be that the art is the higher form. I thought Jean put her finger right on it. (139)

Citing several examples in The Inner Reaches of Outer Space, with each example serving as a further exposition of its predecessor, Campbell persists with the theme about the lack of the mystic's craft, thus the inferior position of the mystic in relation to the artist and its influence in the phenomenal world: "The craft holds the artist to the world, whereas the mystic, facing inward, may be carried to such an extreme posture of indifference to the claims of phenomenal life as that of the old yogi with his parasol of grass in the Hindu exemplary tale, 'The Humbling of Indra'"(Inner Reaches 89).

Campbell elaborates on the theme in a subsequent example, this time elevating the position of the priest above that of the mystic, when he writes: "The priest's practical maxims and metaphorical rites moderate transcendent light to secular conditions, intending harmony and enrichment, not disquietude and dissolution. In contrast, the mystic deliberately offers himself to the blast and may go to pieces" (Inner Reaches 91). Evelyn Underhill, however, stands in direct opposition to Campbell's statement when she claims: Campbell elaborates on the theme in a subsequent example, this time elevating the position of the priest above that of the mystic, when he writes: "The priest's practical maxims and metaphorical rites moderate transcendent light to secular conditions, intending harmony and enrichment, not disquietude and dissolution. In contrast, the mystic deliberately offers himself to the blast and may go to pieces" (Inner Reaches 91). Evelyn Underhill, however, stands in direct opposition to Campbell's statement when she claims:

The true mystic sees Reality in its infinite aspect; and tries, as other artists, to reveal it within the finite world. He not only ascends, but descends the ladder of contemplation; having heard "the uninterrupted music of the inner life," he tries to weave it into melodies that other men can understand. (Essentials of Mysticism 66)

As a final announcement of the theme, Campbell declares: "The way of the mystic and the way of the artist are related, except that...the mystic may come to regard the world with indifference, or even disdain" (112). Campbell continues with his illustrious argument about how "in the literature of asceticism passages abound of disparagement of the body, its functions and its motivations," by citing an example of the ascetic Swami Vivekananda who, "...when on the point of death was heard to mutter, 'I spit out the body'" (112). In reference to Vivekananda, Campbell points at the mystic's lack of compassion (love) for other forms of life, in contrast to the artist, about whom he says, "...has been held by his craft in love to the world as it is, regarding with equal eye the Brahmin, the dog, the eater of dogs, the slayer and the slain, cannot but recognize in each...something of himself" (112).

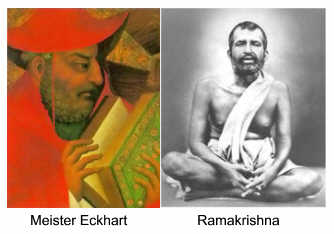

When Campbell does shed positive light on the mystic, he does so in reference to the exceptional mystic, Meister Eckhart, and the saint, Ramakrishna (39); he implies that their greatness resides in the ultimate sacrifice of their high spiritual trajectory of Divine union for being of service to the phenomenological dimension. Campbell mentions "...a third position, typified in the Mahäyäna Buddhist ideal of the Bodhisattva, whose 'being or nature'...is 'enlightenment'...and who yet with unquenched 'compassion'...for his or her fellow creatures has either remained in or returned to this suffering world, to teach" (41). Ramakrishna, the Dalai Lama, and Christ, Campbell states, are such examples (41). He does not, however, refer to teaching as a craft.

Campbell's repeated statements about the lack of the mystic's craft — thus art being the higher form because of its craft — does not convince: Not only do I hold in question Campbell's statement that the mystic lacks a craft, but also that such a craft inherently exempts the artist from the trappings of the mystic's disembodied spirituality and the ambitious pursuit of self-interest spurred on by a lack of love, love that could only find expression through such a craft. For an exploration of these fundamental concerns, I turn to Evelyn Underhill, about whom T.S. Eliot wrote: "Her Studies...have the inspiration not primarily of the scholar or the champion of forgotten genius, but of the consciousness of the grievous need of the contemplative element in the modern world" (Greene 2). Campbell's repeated statements about the lack of the mystic's craft — thus art being the higher form because of its craft — does not convince: Not only do I hold in question Campbell's statement that the mystic lacks a craft, but also that such a craft inherently exempts the artist from the trappings of the mystic's disembodied spirituality and the ambitious pursuit of self-interest spurred on by a lack of love, love that could only find expression through such a craft. For an exploration of these fundamental concerns, I turn to Evelyn Underhill, about whom T.S. Eliot wrote: "Her Studies...have the inspiration not primarily of the scholar or the champion of forgotten genius, but of the consciousness of the grievous need of the contemplative element in the modern world" (Greene 2).

Underhill challenges Campbell's and others' predominantly negative stances on the mystic in her essay, The Mystic as Creative Artist, when she states:

Hostile criticism of the mystics almost invariably includes the charge that their great experiences are in the nature of merely personal satisfactions. It is said that they stand apart from the ruck of humanity, claiming a special knowledge of the supersensual, a privilege of communion with it; yet do not pass on to others, in any real and genuine sense, the illumination, the intuition of Reality, which they declare that they have received. (64)

In response to such criticism, Underhill points out that the mystic "...is not a spiritual individualist" (64), but enters into the divine and sacred as an "...ambassador of the race" (64) who has the obligation of the mediator "...between the transcendent and his fellow-men" (64). The calling of the mystic, the author states, is that of the "...creative artist of the highest kind; and only when he is such an artist, does he fulfill his duty to the race" (65). Some of the exemplary mystical poets, according to Underhill, are: Vaughan, Blake, Whitman, Thompson, St. John of the Cross, Rumi, Hopkins (70-71), and one might add, Emily Dickinson. In response to such criticism, Underhill points out that the mystic "...is not a spiritual individualist" (64), but enters into the divine and sacred as an "...ambassador of the race" (64) who has the obligation of the mediator "...between the transcendent and his fellow-men" (64). The calling of the mystic, the author states, is that of the "...creative artist of the highest kind; and only when he is such an artist, does he fulfill his duty to the race" (65). Some of the exemplary mystical poets, according to Underhill, are: Vaughan, Blake, Whitman, Thompson, St. John of the Cross, Rumi, Hopkins (70-71), and one might add, Emily Dickinson.

Since Underhill unequivocally affirms the mystic's craft, the essential expression of such a craft deserves analysis, brief as it may be. In reference to mystical literature, the author explains:

Roughly speaking, he has two ways of doing this, by description and by suggestion; and his best successes are those in which these two methods are combined. His descriptions are addressed to the intellect, his suggestions are appeals to the imagination of those with whom he is trying to communicate. (Essentials 68)

Underhill continues to elucidate the spiritual depths of the mystic's artistic self-expression, when she writes: "...he can enter his holy of holies whenever he will. Hence he is able, in a deeper sense than is possible to the artist, to unite himself with the very being of Reality..." (Bergson 52). This observation paves the way for a return to Campbell's earlier statement wherein he ascribes to the artist's valuable contribution of service, the essential gravitational pull of love, which directs the artist along a course of selfless service to all of physical creation. Having established that the mystic indeed does have a craft, one may hence claim that the principle of love permeates at least in equal measure the life of the mystic as it does that of the artist.

Speaking of love in his concluding chapter, "At the Close of an Age," Campbell presents a most expansive view of love as the only solution for healing the blights of contemporary humanity: "...if the principle of love cannot be wakened actually within each...to master the principle of hate, The Waste Land alone can be our destiny and the masters of the world its fiends" (Occidental 521). One does not have to search far to encounter evidence in contemporary society of the Waste Land's rapid expansion; in Campbell's own words: "The Waste Land is that territory of wounded people...of people living inauthentic lives, broken lives, who have never found the basic energy for living, and they live, therefore, in this blighted landscape" (Thou Art That 23).

Psycho-spiritual evidence abounds of symptoms stripping bare the sterile soil of the impoverished soul, ignorant of its longing, a yearning of the heart that has taken silent flight into the mystery of its own existence. Oriented to the prosaic Waste Land only, many are blind to the sacred outward-bound trail leading to a promised land of resurrected life. It is therefore the true artist's and mystic's responsibility to lead the way to that dimension which Campbell describes in reference to Webster's as "...'that which arouses sentiments of awe and reverence and a sense of vastness and power outreaching human comprehension'" (Inner Reaches 92). The craft needed to return humanity anew to the essence and the directives of the divinely inspired soul is the mystical function of myth, what Campbell describes as "the first and most distinctive — vitalizing all— ...that of eliciting and supporting a sense of awe before the mystery of being" (Occidental 519). In her essay, The Future of Mysticism, Underhill claims that two conditions are required by the mystic to awaken the parched soul from its Waste Land to the sacred wellspring of awe:

First, the appearance of one or more great mystics, centres of spiritual vitality, revealing in their works and their example the loveliness and unfathomable reality of that supernal world on which they live; next, a condition of public opinion sympathetic to the mystic's revelations, a generally experienced need of some more durable object of desire, some more real satisfaction of the heart's craving, than any that can be found amongst the changing circumstances of human life. (65)

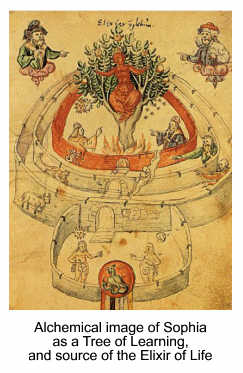

Keeping in mind the parallel between the artist's and mystic's way, I pose the following question: What constitutes the essential element of the true mystic and artist that is so conducive to (divine) inspiration of a high order? In reference to the artist, Campbell ascribes to James Joyce's insight on the subject: "...proper art is of the static state of the mind and eye that have been 'arrested and raised above' these conditioning factors by which vision is prejudiced and actuality overshadowed..." (Inner Reaches 107). Addressing the essential propensity of the mystic for alignment with the greater intelligence of the Divine, Underhill explains: "The first is the experience of the great mystic in his hours of ecstatic contemplation, when his little rhythm is merged in the great rhythm of the transcendent world: when the soul, in Boehme's words, 'joins hands and dances with Sophia the Divine Wisdom" (Bergson 60). Keeping in mind the parallel between the artist's and mystic's way, I pose the following question: What constitutes the essential element of the true mystic and artist that is so conducive to (divine) inspiration of a high order? In reference to the artist, Campbell ascribes to James Joyce's insight on the subject: "...proper art is of the static state of the mind and eye that have been 'arrested and raised above' these conditioning factors by which vision is prejudiced and actuality overshadowed..." (Inner Reaches 107). Addressing the essential propensity of the mystic for alignment with the greater intelligence of the Divine, Underhill explains: "The first is the experience of the great mystic in his hours of ecstatic contemplation, when his little rhythm is merged in the great rhythm of the transcendent world: when the soul, in Boehme's words, 'joins hands and dances with Sophia the Divine Wisdom" (Bergson 60).

Finally, I propose: the greatness of the true artist and the mystic — no, all of humanity — is contained herein: to choose to love beyond the little self; for is the paramount craft that holds everyone in service to this world, not love?

Works Cited:

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on his Life and Work. Edited by Phil Cousineau. Novato, California: New World Library, 2003.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor as Myth and as Religion. Novato, California: New World Library, 2002.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Creative Mythology. New York: Penguin Compass, 1976.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology. New York: Penguin Compass. 1978.

- Campbell, Joseph. Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor. Edited by Eugene Kennedy. Novato, California: New World Library, 2001.

- Greene, Dana, ed. "Introduction." Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy. Albany, New York: State U of New York P, 1988.1-29.

- Underhill, Evelyn. The Essentials of Mysticism and Other Essays. London: Dent and Sons, 1920.

- Underhill, Evelyn. " Bergson and the Mystics." Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy. Edited by Dana Greene. Albany, New York: State U of New York P, 1988. 47-60.

- Underhill, Evelyn. "The Future of Mysticism." Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy. Edited by Dana Greene. Albany, New York: State U of New York P, 1988. 61-66.

Wilhelm Oosthuizen was born in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where he lived until he immigrated to the USA in 1992. Shortly after his arrival, he continued with his career as a medical/surgical traveling nurse followed by work as a hospice nurse. Some of his primary interests include: music, mysticism, intuition, film, and global humanitarian and ecological concerns. Wilhelm is currently enrolled in the MA/PhD Program in Mythological Studies with an emphasis on Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute in California where he currently resides. Wilhelm Oosthuizen was born in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where he lived until he immigrated to the USA in 1992. Shortly after his arrival, he continued with his career as a medical/surgical traveling nurse followed by work as a hospice nurse. Some of his primary interests include: music, mysticism, intuition, film, and global humanitarian and ecological concerns. Wilhelm is currently enrolled in the MA/PhD Program in Mythological Studies with an emphasis on Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute in California where he currently resides.

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|