|

Winter Fool, Summer Queen:

Shakespeare's Folklore and the English Holiday Cycle

Copyright © 2003 by Kristin McDermott.

This article first appeared in Realms of Fantasy magazine, 2003 and later in the Endicott Studio website. It is reprinted with the author's permission.

Kristen McDermott is an Assistant Professor of English Literature at Central Michigan University, specializing in Early Modern English Studies (particularly Drama and Theater History) and Shakespeare. She attended Mythic Journeys '06 as a Guest Presenter.

In winter's tedious nights sit by the fire

With good old folks and let them tell thee tales

Of woeful ages long ago betid.

(Richard II 5.1)

The best production of The Tempest I ever saw wasn't in a professional theater. It was in a grade-school auditorium, and a 20-year-old actor sat on the edge of a bare stage with a guitar. With no preamble, he started to play and sing Bob Dylan's folksong, "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall." Then ten more young actors from the Shenandoah Shakespeare Express ran onto the stage with a rope that they magically transformed into the riggings of a ship. They threw themselves around the stage making "wooshing" sounds with their mouths and thunder with their feet, and all of a sudden we were in the middle of a storm at sea.

I imagine that going to the theater was a bit like this for Shakespeare's audience. The plays they watched were not original stories, but familiar ones: English history, adaptations of Italian novels and Roman comedies, retellings of ancient British legends. Playgoers in Shakespeare's time attended plays for the pleasure of hearing beloved stories well told. They also got familiar folk songs, the excitement of seeing well-trained bodies in motion, and a few special effects created out of not much more than bits of string. How did these nice little entertainments end up becoming "great" English literature?

Many fantasy writers have tried to imagine how Will Shakespeare got his gift for turning mere stories into works of wonder. Neil Gaiman, in his wonderful Sandman series, has young Will Shakespeare commissioned by Morpheus, the King of Dreams, to write A Midsummer Night's Dream to be presented to Oberon, the Faery King, and his court. Morpheus confers on Will the power to bring dreams to life, on the condition that he write one more faery play (which turns out to be The Tempest) at his career's end. Sara Hoyt, in Ill Met By Moonlight, envisions a beautiful faery shape-shifter named Quicksilver, residing in the forest of Arden (just outside Stratford), as Shakespeare's male and female muse and guide to the realm of the Otherworld.

In truth, Shakespeare has almost become part of the folklore of the English-speaking world himself—his mysterious origins and awe-inspiring poetic gifts lead many to see him as a semi-divine figure; little wonder that we fantasize about where such genius came from.

Shakespeare was a master fantasizer himself, and a few of his 38 plays feature visitations from faeries, witches, magi, airy spirits and ghosts. Most of them, though, present earthly kingdoms that range from the legendary realms of Ancient Rome to Athens and pre-historic Briton, to the great Renaissance courts of Venice and Vienna and the exotic sands of Morocco and Cyprus. But why should Ophelia, noblewoman of Denmark, sing the songs of an English milkmaid? Why are there references to the Feast of St. Stephen in King Lear, which is set in pre-Christian England, or to St. Valentine's Day in A Midsummer Night's Dream, set in ancient Athens? Why is a play set in the legendary middle-eastern kingdom of Illyria called Twelfth Night? Shakespeare's rural English background comes through in the way he embeds rural and folk holiday traditions in his plays, which generally take place anywhere but the English countryside.

Busy as city life was, going to the theater was a mini-holiday for many Londoners. The plays were presented in the afternoon to make use of natural light (the Globe Theater was an open-air amphitheater), so workers, students and apprentices had to play hooky to attend. His audience was made up of a cross-section of London's population at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Many folk were drawn to the opportunities of London from the countryside, where "partitioning" turned increasing amounts of farmland over to the more lucrative production of wool, throwing many rural farmers out of a job. Shakespeare himself was a country boy: he grew up in the market town of Stratford-on-Avon about 90 miles from London, the son and husband of prosperous farmers' daughters.

He came a long way in a few years: by the time he was 30, Shakespeare's plays were a fixture at the royal court, where they were usually presented as part of the holiday festivities stretching from Hallowmas (November 1) to Shrovetide (the beginning of Lent). Modern-day scholars are very interested in the association between drama and holidays because they believe that the medieval church feasts of Yuletide (the twelve days of Christmas) and Carnival (Mardi Gras: the day before Lent begins on Ash Wednesday) were times specially set aside for the common folk to blow off steam by mocking their social superiors. These were the days set aside to celebrate the "World Upside Down," when children and fools could lawfully pretend to be bishops and kings. The customs of these special times demanded indulgence in food and drink (because they celebrated the carnality of Christ), as well as the all-important masking or disguising.

Masks are the key element of Carnival, allowing revelers to pretend to be someone they're not, and also to protect themselves should they go a little too far. In England, holidays year-round (but especially Christmas and Midsummer) were marked by visits from masked mummers to the great houses. There, local folk would sing, gambol, and act out myths and legends, which always featured topical jokes and lampoons of the local gentry. For a brief time, the rural people were allowed to express their true feelings about the great folk while under the protection of their masks and the holiday spirit. They were even rewarded for their cheekiness with food, drink and money, because their noble hosts knew that such "license" was only temporary, and the next day these wickedly witty performers would go back to being humble peasants.

The professional stages of Shakespeare's London were direct descendants of the mummers' plays, removed from the great houses and given homes of their own. Inside the Globe Theater, historians believe, a kind of permanent Carnival took place. The audience was made up of people from many social classes, mixing together in a way they never would anyplace else in London. The actors were workingmen dressed up in borrowed finery as kings and gods. The stories the audience came to see and hear were also a hodgepodge of comedy and tragedy, history and fantasy. The language was a gallimaufry of high love poetry and crude expletives, with every other kind of English in between.

It shouldn't surprise us that the art of drama is closely tied to holiday activities. Folklorists have long drawn connections between drama and religious ritual, and religious ritual is, of course, one of the main roots of our traditional Western holiday cycle. The other source is the collection of traditions associated with the yearly calendar of planting and harvest, and the greater, ever-turning cycle of birth, death and rebirth that is the land's way of marking time. Put them together—land and church, natural rhythms and human ways of marking them—and you have a portrait of the world in which William Shakespeare was born and for which he wrote his great plays. His world was equal parts rural and urban, arcane and everyday, magic and marketplace.

Two of Shakespeare's best-loved plays actually have holidays for titles—A Midsummer Night's Dream and Twelfth Night. They might have been given those titles to commemorate their first performances on those holidays—a Midsummer wedding at a noble estate, and for the Twelfth Night celebration at court. Both joyfully celebrate the giddiness of a world turned upside-down through disguises and love-play.

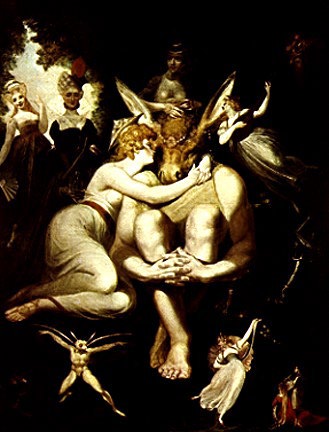

In Midsummer, four lovers and six amateur actors are pixy-led through the woods outside Athens. Mistaken identities cause chaos, not the least for Titania, the Queen of Faery, whose husband, Oberon, has charmed her so she falls in love with a common weaver named Bottom, who has been given an ass's head by the mischievous faery Puck. There's a darker confusion underlying the story, though—Oberon and Titania have been separated for some time, fighting over possession of a changeling baby. Because they are earth spirits, their divorce has frightening repercussions for the land:

. . . the winds, piping to us in vain,

As in revenge, have suck'd up from the sea

Contagious fogs; which falling in the land

Have every pelting river made so proud

That they have overborne their continents:

. . . the green corn

Hath rotted ere his youth attain'd a beard;

The fold stands empty in the drowned field,

And crows are fatted with the murrion flock.

(2.1)

In other words, the earth responds to their discord with flood, pestilence and famine. Even worse, though, the seasons—and their holidays—have altered:

The human mortals want their winter here;

No night is now with hymn or carol blest:

. . . the spring, the summer,

The childing autumn, angry winter, change

Their wonted liveries, and the mazed world,

By their increase, now knows not which is which.

(2.1)

Shakespeare knew that Midsummer—the Summer Solstice—was a delicate time for farmers. Poised midway between the seasons of planting and harvest, the summer weather could make or break the season's crops. Summer Solstice bonfires were not kindled to call back the sun, as Winter Solstice fires were, but to purify land and animals from the diseases of warm weather. Urban audiences knew that summer was a perilous time in the city too—the season of plague and other "contagious fogs," sucked up from the sewage-filled Thames. Watching the dancing night spirits of the countryside putting all right through the power of love, however, was probably a welcome relief from the spirits of fever, rat, and flea that haunted their own hot, cramped rooms.

For another cool change, audiences loved well Shakespeare's festive comedy Twelfth Night, in which the world-upside-down-ness of the Christmas season infects a tale that has nothing to do with Christmas. It has everything to do, though, with disguising and mumming. Viola, a shipwrecked teenager, hopes to survive in the strange land of Illyria by disguising herself as a boy singer named Caesario to serve the Count Orsino. Her disguise fools everyone, probably because she learned boy's ways from her twin brother Sebastian, believed lost at sea. Orsino sends her to visit the beautiful Countess Olivia and deliver his vows of love, but complications arise: Viola is a reluctant messenger, because she has fallen in love with Orsino herself, and Olivia, who doesn't love Orsino, instead falls in love with the handsome "Caesario." The gender-bending humor that ensues is a classic example of the world upside-down.

As in Midsummer, though, there is a dark undertone to the holiday mirth. A subplot concerns Olivia's drunken uncle, Toby Belch, and his ongoing feud with her uptight butler, Malvolio. Toby and his bumbling friend, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, love drinking, dancing, singing, and laughter. Their partner-in-partying, Olivia's jester, Feste, is actually named for the spirit of festivity. When Malvolio interrupts one of their midnight songfests and threatens to tattle to Olivia, Toby snarls at him, "Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?" With this line, we see that Malvolio represents the Puritan suspicion of Anglican church festivals, called "church ales," which, like rural celebrations, often featured freely flowing ale and sweets to attract the less-than-devout to holy services. Toby suspects Malvolio of wishing to suppress all holiday pleasure, not just his own. In this way, Malvolio plays the traditional role of the grim Winter King, who must be killed or banished for the sake of festivity.

Toby's revenge against Malvolio is swift and terrible. He tricks him into thinking Olivia is in love with him, and, when Malvolio appears before Olivia wearing an outlandish lover's getup of yellow stockings and ribbons, Olivia believes him mad and prescribes the common treatment of isolation in a dark room. Feste appears to him disguised as a priest and tries to exorcise Malvolio's demons, forcing him to confess his sinfulness. Twelfth Night, then, is titled for Christmas, but simultaneously reflects the activities of Carnival and Lent. Malvolio must do penance—he must become the sin-eater or scapegoat who suffers for the follies of the disguise-loving mortals around him—before the confusions about Viola's identity and who loves whom can be cleared up.

Holidays also figure prominently in plays not actually named for them. In The Merchant of Venice, the Jewish moneylender Shylock worries about his house's safety during the Carnival festivities in the streets:

What, are there masques? . . .

Lock up my doors, and when you hear the drum

And the vile squealing of the wry-necked fife, . . .

Stop my house's ears . . .

Let not the sound of shallow foppery enter

My sober house.

(2.5)

He's right to worry: trashing the Jewish quarter was also a popular part of Christian celebrations of the Easter season in the anti-Semitic world of Early Modern Europe. This happens indirectly, though: a masked Venetian reveler elopes with his daughter and his moneybox.

This comedy has an even darker undertone. It concerns itself mainly with the fairy-tale story of the wealthy Lady Portia, whose hand can only be won by a suitor who guesses a riddle correctly, choosing among three caskets of gold, silver, and lead for the one that contains her picture. But her favored suitor, Bassanio, has a friend named Antonio—the merchant of the title—who is in mortal danger. He has jokingly signed a contract with Shylock promising to pay him a pound of his own flesh if he can't repay a loan, and the loan has come due just as Antonio's ships have all sunk. Antonio faces certain death if Shylock—who bears a grudge against the Venetian Christian community for countless humiliations besides the loss of his daughter—won't forgive the loan.

There are many references, of course, to Christian sacrifice and the Easter season in such a story, but it also counts on the audience's familiarity with the fearful folk belief that Jews at night (and especially at Easter) became vampires, cannibals, werewolves—ravenous eaters of Christian babies and drinkers of Christian blood. Shylock is repeatedly referred to as "wolfish," calling up fears of those shape-shifting flesh-eaters. These fears overwhelm the more religious notes of the tale, and it is not by the Christian "quality of mercy," but only by another brilliant masking that Antonio is saved. Portia dresses as a man and poses as a lawyer at the court hearing of Shylock and Antonio's dispute. Her disguise is completely convincing, and she wins the case, finding a loophole to free Antonio from Shylock's contract. Like Malvolio, Shylock is identified as the enemy of holiday mirth and is humiliated and banished, and the lovers are free to celebrate the life-giving pleasures of the flesh.

The carnival world shows up in the more somber context of Shakespeare's great tragedy, King Lear. This, too, is a world upside-down, where a father—the mythic King Lear—banishes his favorite daughter for failing to brag about her love for him, and a loving son is condemned to death because his illegitimate brother accuses him of plotting to murder his own father. For Shakespeare, the darkest dark side to the merry world of Carnival was the possibility it opened up that even our most sacred ties of love and respect could be jettisoned.

The dismayed and frightened voice of this particular world is that of Lear's jester. He is the opposite of Twelfth Night's Feste—where Feste mocks fools who are too rigid and too serious, Lear's Fool mocks the King for failing to respect the natural order of things:

LEAR

When were you wont to be so full of songs, sirrah?

FOOL

I have used it, nuncle, ever since thou madest thy daughters thy mothers: for when thou gavest them the rod, and put'st down thine own breeches,

Then they for sudden joy did weep,

And I for sorrow sung,

That such a king should play bo-peep,

And go the fools among.

(1.4)

The Fool's voice is the voice of the powerless who fear the damage the powerful can do when they begin to lose their grip on sanity. Lear has given his crown to his two remaining daughters and trusts them to give him a home. However, they refuse unless he gives up his royal retinue of servants and soldiers, and the proud Lear prefers to be homeless. The Fool follows the King across a stormy wasteland, crying from cold and exhaustion, but unwilling to leave his master alone. The "good and faithful servant" who wastes his life in the service of a man who doesn't appreciate him is, in this play, accompanied by a number of references to St. Stephen's Day—the day after Christmas, nowadays called Boxing Day, when traditionally the great reward the lowly for their service.

We know that this play was actually performed before King James on December 26, 1606; whoever chose the plays for royal performances had a keen sense of their folk significance. Stephen's feast was traditionally the day of the Christmas season associated with "good housekeeping" and charity. Great folk were reminded by carols such as "Good King Wenceslaus" (who brought food and fire to a poor man "on the Feast of Stephen") to share their Christmas plenty with the poor, and the "poor boxes" were opened in the churches. The begging on this day could get fairly aggressive, and rich manors hastened to avoid being labeled a "hard house," subject to "forced giving."

King Lear and his Fool are turned away from Lear's daughter's house and sent into a winter storm—the reverse of the Wenceslaus legend. Popular sayings insisted, "Blessed be St. Stephen/There's no fast upon his even," and King James I, who valued traditional customs highly, even made hospitality on this day a law. But Lear's daughters violently break this law, refusing shelter not just to the poor, but to their own father.

The Fool sees where this is headed with tragically wise eyes:

When nobles are their tailors' tutors;

No heretics burn'd, but wenches' suitors;

. . . When usurers tell their gold i' the field;

And bawds and whores do churches build;

Then shall the realm of Albion

Come to great confusion:

. . . This prophecy Merlin shall make; for I live before his time.

(3.2)

Referring to the legend of Arthur, the "King under the Hill," the Fool knows that the breaking of this King means the breaking of the land.

Another popular centerpiece of the Christmas season, the "Feast of Fools" also began on St. Stephen's Day and lasted until December 28 (the Massacre of the Holy Innocents). The focus of this three-day holiday-within-a-holiday was Christianity's message of hope for the weak and powerless, but many popular traditions grew up around this festival to take advantage of the Church's temporary tolerance—even celebration—of foolish and chaotic behavior. The "Lord of Misrule," chosen in rural and urban observances of this festival, presided over mummings, dances, drinking games and songs, his purpose being to encourage chaos and silliness.

This is exactly what Lear becomes after he abdicates his responsibilities as King. His thoughtless division of the kingdom opens the door to chaos and mayhem as his two daughters plot against one another and his third daughter brings an army from France into England to challenge them. Lear's madness in the storm becomes an outward symbol of the misrule he has unleashed on the land. But even King Lear, in his madness, gains some of the Fool's perspective:

Poor naked wretches, whereso'er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop'd and window'd raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta'en

Too little care of this!

(3.4)

Realizing at last that the poor suffer most for the sins of the great, he admits he has been careless. He has lost a kingdom, but has gained much-needed compassion for the common folk.

Shakespeare's audience would have been particularly moved by this plot. Many of them were, like Shakespeare himself, young folk who had to leave home and family to seek their fortunes in the city. Living in an impersonal metropolis may well have made people long for the security, however patronizing, of the manor and the farm, where people knew their place and strong customs demanded that the rich look after the poor.

In London, of course, the poor disappeared from sight into dark alleys and tumbledown tenements, while the wealthy kept to their banqueting halls and never saw the people who washed their clothes or groomed their horses. The countryside's sense of community disappeared, and King Lear offers a poignant metaphor for the chaos that occurs rapidly when those on top forget their duties to those on the bottom.

Such tales inserted popular holiday associations into mythic settings in order to help their audience connect with a deep well of shared history and national identity. King Lear is a tale from England's pre-literate legends; its plot is drawn from the ancient tales, "Cap O' Rushes" and "Love Like Salt," both of which deal with a daughter's love for her undeserving father. Evoking the day of St. Stephen—with its equal share of church and folk elements—Shakespeare creates a sense of continuity between ancient hearthside tales and newfangled church-and-town customs.

Sometimes Shakespeare took the opposite strategy, depicting country customs onstage for the amusement of his courtly audience members. One of his late plays, The Winter's Tale, evokes the custom of tale-telling by the fireside at the death of the year. Such tales are often tales of suffering and redemption, and this one is no different. A well-respected King, Leontes, takes the sudden notion that his pregnant wife, Hermione, has slept with his best friend, who is making a winter holiday visit. Enraged, Leontes publicly accuses and imprisons Hermione, where she apparently dies of grief after giving birth to a girl, Perdita. The maddened King orders that the baby girl be killed, but his servant, unwilling to do such a horrible deed, merely leaves the girl at the seashore to be adopted by a common shepherd.

When we next see our fairy-tale lost princess, sixteen years have passed and she is about to be crowned Queen of the Sheep-Shearing festival. In England, the traditional date of this festival was around June 5: this is a feast of high summer in spite of the play's wintry title. A couple of courtly visitors come by to watch the charming country festivities, and Perdita (who has no idea that she's a princess) greets the visitors in the deeply coded language of flowers:

Reverend sirs,

For you there's rosemary and rue; these keep

Seeming and savour all the winter long:

Grace and remembrance be to you both,

And welcome to our shearing!

(4.4)

Oddly, she offers winter herbs. The visitors comment that her choice was a gracious reference to their own mature years, but Perdita answers that, since it's high summer, her favored spring flowers are gone, and the only available garden flowers are "our carnations and streak'd gillyvors,/Which some call nature's bastards." She then offers a more appropriate herbal bouquet:

Here's flowers for you;

Hot lavender, mints, savory, marjoram;

The marigold, that goes to bed wi' the sun

And with him rises weeping: these are flowers

Of middle summer, and I think they are given

To men of middle age. You're very welcome.

(4.4)

The "language of flowers" has a long tradition made up of equal parts folk and classical sources. The bouquet Perdita offers comments wittily on the place, season, and celebration at hand. Lavender and mint are herbs used to preserve fleeces from insects, but they are also known as "hot" herbs in reference to the doctrine of humors. All living things, in this system, are made up of a combination of hot and cold, wet and dry elements. "Hot" herbs have properties to counteract the "coldness" of winter, age, and other "cold" maladies like melancholy or rheumatism. Savory and marjoram in particular were herbs of love—even aphrodisiacs—and often part of bridal bouquets, as were mint and lavender. The marigold's Latin name is calendula, and it was believed that this flower constantly turned its head to the sun, tracking it through the day. A herbal timekeeper, it was associated with the cycle of the year.

Perdita, the Winter child and Summer Queen, wears so elaborate a garland that she is compared to Flora, goddess of Spring, clothed all in flowers—though it's late summer. In this play, she represents Time, which is so easily lost (perditus in Latin) by the careless. There are a number of seasonal mix-ups in her presentation—maybe Shakespeare was subtly poking fun at his courtly audience, who probably wouldn't know enough about the countryside to notice the inconsistencies. Or perhaps Perdita, a winter-born child, views both the spring symbols and the summer ones with suspicion, and feels more comfortable with the wintry qualities of wisdom, introspection, judgment and high rhetoric.

The important thing is that Perdita, a noblewoman even if she doesn't know it, has a classical, courtly approach to the language of flowers. Her loving foster-father, however, admits she's not much of a country hostess:

Fie, daughter! when my old wife lived, upon

This day she was both pantler, butler, cook,

Both dame and servant; welcomed all, served all;

Would sing her song and dance her turn; now here,

At upper end o' the table, now i' the middle;

On his shoulder, and his; her face o' fire

With labour and the thing she took to quench it,

She would to each one sip. You are retired,

As if you were a feasted one and not

The hostess of the meeting . . .

Come, quench your blushes and present yourself

That which you are, mistress o' the feast: come on,

And bid us welcome to your sheep-shearing,

As your good flock shall prosper.

(4.4)

Perdita may look the part of the Queen of the Sheep-Shearing, but she neglects the homely duties of cooking, hostessing, drinking, and even dancing on the table. These activities, of course, were necessary for the "good flock" to "prosper"—in the folk ritual of sympathetic magic, the Queen of the Flock needed to enhance her own fertility to ensure that of the sheep! The "hotness" or appropriateness of the bouquet was not nearly as important as the sexual attractiveness of the Shearing Queen. Perdita carries the floral symbols of fertility, but is hesitant to engage in activities like dancing and drinking that so often lead to more "fertile" activities.

It's as if Perdita knows at some level that her rural identity is really a disguise. She herself seems uncomfortable with her "goddess-like" getup. She notes that she's acting like Whitsuntide (May 15) players, perhaps because she's wearing a costume: "sure this robe of mine/Does change my disposition." The Whitsuntide players and Morris-dancers often dressed as "green-men" or wild forest men, and wore bells and garlands of ivy and greens as they danced—in fact, the party features a "dance of satyrs," classical figures of fertility. These dances were often ribald; perhaps it's the bawdy aspect of Whitsun-players that makes Perdita nervous about looking like one.

Her fears are well founded. The shepherd she loves and dances with is a disguised prince, and his father, the King of Bohemia (one of the elderly visitors, himself in disguise), angrily forbids his son to marry a common shepherdess. Perdita, dismayed, promises "queen it no inch farther,/But milk my ewes and weep."

Because this is a fairy tale, though, all comes right in the end. The Winter's Tale is designed for a courtly audience, so its folk elements are "tamed" into the mere setting of sheep-shearing and flower-gathering. Perdita is quickly removed from her adopted home, because the values of this tale are the courtly ones of contemplation, forgiveness, self-control, loyalty, and seeing through disguises. The tale soon returns to the court of the penitent Leontes, where Perdita is reunited with her family and her shepherd-prince, and forgets her childhood in the country.

. . . Now I want

spirits to enforce, art to enchant;

And my ending is despair

Unless I be redeemed by prayer . . .

(The Tempest, Epilogue)

The Winter's Tale is a rare "courtly" play for Shakespeare; although his plays were often performed at court, it seems clear that his intended audience was the average Londoner. In his final play, Shakespeare creates a magician named Prospero who, with nothing but magical words, has

. . . bedimmed

The noontide sun, called forth the mutinous winds,

And 'twixt the green sea and the azured vault

Set roaring war . . . . Graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, ope'd, and let 'em forth

By my so potent art.

(5.1)

However, after getting his enemies to admit their wrongs to him and finding his daughter a suitably princely husband, he gives up his "rough magic" in favor of a return to court. This is not a happy choice; he notes that, once he leaves the island, "My every third thought will be my grave." Shakespeare, who would shortly take his theatrical profits and retire to Stratford to be a wealthy landlord, was probably equally ambivalent about leaving the stage for a quieter, soberer, more contemplative life. He only lasted three years as a courtly gentleman; it seems that his heart was back with his "spirits" in the London theaters.

Shakespeare, the master tale-teller, knew that his audience was made up of people who, like him, both hated and loved their city. In smoky, crowded London, it must have been difficult to see the sun or to experience the change of season as vividly as in the country; Shakespeare offered his playgoers a temporary taste of holiday pleasures, reminders of the rural cycle of the year. His references to such holidays became an effective way to create emotional depth in stories whose plots were familiar and whose themes might otherwise be awe-inspiring or even depressing. Literally evoking tales told by the hearth, at a mother's knee, he forged a link between the folkloric and the historic, between the personal and the political. We may no longer "get" all the references; we may no longer ourselves be in touch with the rural rituals that his plays invoke, but like Shakespeare's audience, we yearn to be part of a larger story, to put down roots into the past. His plays give us that chance to connect with the stories that make us human.

Art

- Henry James Nixon, The Tempest

- Henry Fuseli, Titania and Bottom (1786-89), Tate Gallery, London

- Walter Howell Deverell, Twelfth Night (1850), Forbes Magazine Collection

- Sir John Gilbert, Shylock After the Trial, Charles Knight's two-volume Imperial Edition of The Works of Shakespere (London: Virtue and Company, 1873-76

- William Dyce, King Lear and the Fool in the Storm (c. 1851), National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburg

- Augustus Leopold Egg, A Scene from "The Winter's Tale" (1845), Guildhall Art Gallery, London

- Charles R. Leslie. Florizel and Perdita, 1837, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Charles Knight's two-volume Imperial Edition of The Works of Shakespere (London: Virtue and Company, 1873-76

Further Reading

Scholarly Resources

- C.L. Barber. Shakespeare's Festive Comedy: A Study of Dramatic Form and its Relation to Social Custom. New York: Meridien, 1959.

- Dale M. Blount. "Modifications in Occult Folklore as a Comic Device in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream." Fifteenth-Century Studies 9, (1984): p. 1-17.

- Thomas A. DuBois. "'That Strain Again!' or, Twelfth Night: A Folkloristic Approach." Arv: Nordic Yearbook of Folklore 56, (2000): p. 35-56.

- Alan Dundes. "'To Love My Father All': A Psychoanalytic Study of the Folktale Source of King Lear." Southern Folklore Quarterly 40, (1976): p. 353-66.

- Phyllis Gorfain. "Contest, Riddle, and Prophecy: Reflexivity through Folklore in King Lear." Southern Folklore Quarterly 41, (1977): p. 239-54.

- François Laroque. Shakespeare's Festive World: Elizabethan Season Entertainment and the Professional Stage. Trans. Janet Lloyd. Cambridge UP, 1991.

- Leah Marcus. "Levelling Shakespeare: Local Customs and Local Texts." Shakespeare Quarterly 42 (1991), 168-78.

- Kristen McDermott: An Early Modern Holiday Calendar.

- Kenneth Muir. "Folklore and Shakespeare." Folklore 92, no. 2 (1981): p. 231-240.

Fantasy adaptations

- Poul Anderson, A Midsummer Tempest (a beloved alternative-history tour de force: a world in which Shakespeare's plays are history)

- Susan Cooper, King of Shadows (a sudden illness sends a teenage boy back in time to inhabit the body of Nat Field, a boy actor in Shakespeare's troupe)

- Pamela Dean, Tam Lin (a contemporary working of the fairy tale, with many allusions to Shakespeare's plays and characters throughout)

- Wendy Froud and Terri Windling. A Midsummer Night's Faery Tale and The Winter Child (two tales of Sneezle, a young fairy in Titania's retinue, are told and richly illustrated with photos of Wendy Froud's enchanting figures)

- Neil Gaiman, A Midsummer Night's Dream (Sandman #19), collected in Dream Country

- Neil Gaiman, The Tempest (Sandman #75) collected in The Wake (in a nice parallel to Shakespeare's play, this is the final issue of the Sandman series and Gaiman's farewell to his readers.)

- Sarah Hoyt, Ill Met by Moonlight and All Night Awake (young Will Shakespeare discovers his poetic inspiration in the form of his "master/mistress," the Faery Lord/Lady Quicksilver)

- Garry Kilworth, A Midsummer's Nightmare (young adult fantasy)

- Terry Pratchett, Wyrd Sisters (a funny treatment of the witches from Macbeth)

- Leon Rooke, Shakespeare's Dog (an irreverent look at Shakespeare's world through his dog, Mr. Hooker's, eyes)

- Marina Warner, Indigo (the events of The Tempest updated and told through the eyes of Caliban's mother, Sycorax, a Caribbean priestess)

- Tad Williams, Caliban's Hour (a sequel to The Tempest, focusing on Miranda's life after leaving the island)

Read more about Kristen McDermott

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|