|

Scaling the Monochord of Music:

An Exploration of Time, Rhythm and Mythology in Sound

©2007 Derek Beres and used with permission

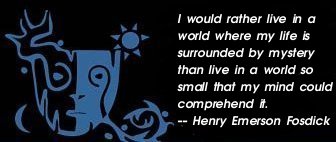

Between the polarities of absolute spirit and absolute matter the Greek philosopher Pythagoras envisioned a single monochord stretched across the spectrum of the universe. Like a skilled musician, the enlightened person would be able to pluck the various frets of planets and sounds with an ease of liquidity. This was considered harmony. For those not trained in the Mysteries, life was discord, as they could not find the proper rhythm of that golden thread. This was known as suffering, which Siddhartha picked up upon during his fateful journey from his kingdom one morning. Between the polarities of absolute spirit and absolute matter the Greek philosopher Pythagoras envisioned a single monochord stretched across the spectrum of the universe. Like a skilled musician, the enlightened person would be able to pluck the various frets of planets and sounds with an ease of liquidity. This was considered harmony. For those not trained in the Mysteries, life was discord, as they could not find the proper rhythm of that golden thread. This was known as suffering, which Siddhartha picked up upon during his fateful journey from his kingdom one morning.

The philosophy of Pythagoras became known as the Music of the Spheres, and he is believed to have created the diatonic scale — quite an achievement for a man that was not a musician, but a mathematician. Still, he was able to envision tones and half-tones stretched between heavenly bodies through a philosophy of numbers, for the basis of math is a rhythm itself. Through patterns of numbers one could understand existence, just as we instinctually recognize a song as either harmonious or dissonant. The philosophy of Pythagoras became known as the Music of the Spheres, and he is believed to have created the diatonic scale — quite an achievement for a man that was not a musician, but a mathematician. Still, he was able to envision tones and half-tones stretched between heavenly bodies through a philosophy of numbers, for the basis of math is a rhythm itself. Through patterns of numbers one could understand existence, just as we instinctually recognize a song as either harmonious or dissonant.

Pythagoras knew that by creating certain tones the human being would react in different ways — some believe he developed his theory by listening to various anvils striking metal. There was no "correct" way to play each note, but through a succession of tones, music was created. Ironically, the success of each sound is reliant upon silence; if there were no quiet, we could not recognize sound. Hence the musician brings beauty into the world — or, should we say, out of it — by noticing the effects of sonic patterns upon his nervous system, which will have like effects on others. For Pythagoras, as for the mythology writers of Hermes and every other god and goddess of song since, music is a shared experience.

There is little coincidence Vedic philosophers devised a similar understanding of this cosmic music centuries before the Greek theorist. They equated the seven chakras along the spine, which traveled from the perineum muscle through the crown of the head, to each have a distinct tone. Like Pythagoras, different notes struck different emotions, and healers could cure physical ailments through music (a practice that continues today). The anahata chakra, located in the chest and symbolic of the opening of the heart, corresponds to the mantra syllable yam, while the ajna chakra, or third eye, opens when the yogi chants om. Like Pythagoras's monochord, the yogis felt the spine was the eternal thread manifest in human form, and by tuning in to certain frequencies the devotee could attain higher states of realization through sound.

Like the yogis, Pythagoras did not judge the discordant sounds as unnecessary. Certainly he assigned them the mode of "evil," for they were the opposite of which harmony and rhythm is to be judged. And yet, like tasting the apple from that perilous garden tree, discord and harmony are kinfolk. When chaparral spreads wildfire across acres of forest, the sound is fierce and destructive. Such storms are followed by the eye, which leads to the most serene sense (and sound) of peace imaginable. As the Taoists used to say, introduce beauty and by default its opposite (or, as the Buddhist claimed, shadow) follows. After Siva dances, a lotus blooms in the rubble.

Just as the geography of the body is defined by sound, countries and cultures resonate on various frets along the string. There are many factors determining the quality of the music created: social climate, weather, agricultural or hunting dependencies, availability of raw materials to build instruments and a host of other underlying themes. The folk music of Morocco is shaped by the bass-like lute sintir and metal castanets known as krakebs. Gnawa musicians sometimes perform one song in an entire overnight ritual, whereupon dancers fall into trance hours into the ceremony. Just as the geography of the body is defined by sound, countries and cultures resonate on various frets along the string. There are many factors determining the quality of the music created: social climate, weather, agricultural or hunting dependencies, availability of raw materials to build instruments and a host of other underlying themes. The folk music of Morocco is shaped by the bass-like lute sintir and metal castanets known as krakebs. Gnawa musicians sometimes perform one song in an entire overnight ritual, whereupon dancers fall into trance hours into the ceremony.  By picking a rhythm upon the monochord and, albeit with slight variation, repeating the tone for hours, they create a hypnosis among the players and that which is played. The qawwalis of Pakistan and Hindustani and Carnatic musicians of India have similar rituals — the latter actually reserve different times of day for ragas to be played. To the traditionalist it would be blasphemous to perform a morning raga in the evening, for the conditions and tones necessary for creating the song would not be congruent. By picking a rhythm upon the monochord and, albeit with slight variation, repeating the tone for hours, they create a hypnosis among the players and that which is played. The qawwalis of Pakistan and Hindustani and Carnatic musicians of India have similar rituals — the latter actually reserve different times of day for ragas to be played. To the traditionalist it would be blasphemous to perform a morning raga in the evening, for the conditions and tones necessary for creating the song would not be congruent.

These practices sound nice, though probably antiquated, to the modern mind. We must remember music was devotion; in India bhakti, or devotional, yoga was performed by mantra chanting (kirtan), something Americans have picked up as the practice has overtaken national consciousness. What we perform today has ancient Hermetic, Vedic and Pythagorean roots intact, for that monochord is not defined by time. Indeed, as the Bhagavid Gita states, "Death is inevitable for the living; birth is inevitable for the dead." Another passage relates the eternal spirit acquiring new bodies as "a man abandons worn-out clothes." Just as plants sprout and drop seed, which becomes the plant the following year, yogic philosophy believes Brahman to do the same with bodies. Music is this expression of our surroundings, a reflection of the world we live within recycled and reinterpreted through the ages. Often what we cannot comprehend in our personal lives we turn into song, as a means of hitting that note we need to heal us.

Again, these theories are difficult if not practiced, remaining abstract thoughts that look quaint on a screen but unrealistic in reality. As Krishna Das once told me, sitting in a room in India for three-and-a-half years with a group of strangers, chanting eight hours a day, was not necessarily enjoyable. His legs grew tired and mind and voice fatigued. Yet eventually when you connect to that "perfect note" (as DJ Cheb i Sabbah once called it when referring to the union of dancers on the floor in front of him), leaving physical, mental and emotional ails behind. They too become parts of the process, and you as performer, or listener, can create an internal alchemy by attuning yourself to the sounds around you — or, put another way, within you. The bhakti yogis believed the sounds rising from their throats would leave during exhalations, while the universe responded with each inhale. Through song there was a synchronicity between the cosmos and humankind, and by tapping into that thread the individual could play along — indeed, yoga is considered lila, "play."

Much of the current distress of the music industry is due to a complete lack of understanding of the nature of music. Global folk music — and this is one of the commonalities in every culture across the board — was not dictated and defined by compatibility to popular format. It was not until songs could be recorded, stored and sold that such packaging began. Hence today you have the idea that people are "stealing" music. For something that was initially a relationship between the world and our race, as well as medicine for the individual dealing with the disparities of discord, the notion that one even "owns" music is ridiculous — much in the way Native Americans thought Spaniards pulling out land deeds were absurd. Unfortunately Columbus and cohorts had gunpowder, as today we have lawsuits.

That argument remains the squabble of an elitist regime who, like all empires, will eventually fall. This is the nature of this world, one Pythagoras understood too well: create too much discord and it will collapse, becoming a vacuous black hole. The panacea for this "problem" is the technologies that human hands have built to make music simpler to create and share. Like any art, simpler does not mean easy. Computer-generated music is often sterile in the mouse clicks of producers that do not know the right notes on the monochord. Yet still, while the media promotes a war in an industry doing everything possible to not lose its lordship, the citizens heal themselves with sound. Pythagoras would most likely have agreed that capitalism and its proponents rest on the side of disharmony.

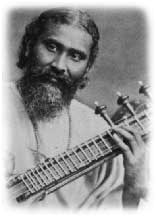

The great Sufi philosopher and veena player Hazrat Inayat Khan remarked, "The secret of composition lies in sustaining the tone as solidly and as long as possible through all its different degrees." Yogis develop ekagrata, the one-pointed focus of the mind (Khan ingeniously called thought "self-directed and controlled imagination"), to be aware of all the mental chatter and emotional stimuli in their body, yet not be governed by it. That is, they learn, quite literally, how to play the scales of their spine, pulling the creative energy known as kundalini from the muladhara chakra and letting it release through the sahasrara. In this way they recognize sadness, despair and suffering, as well as joy, love and equanimity, and yet are not controlled by any of them. The desire for one and denial of another fades — something the Christian-dominated heaven and hell theory needs to learn — and with their thoughts they maintain harmony at all times. The great Sufi philosopher and veena player Hazrat Inayat Khan remarked, "The secret of composition lies in sustaining the tone as solidly and as long as possible through all its different degrees." Yogis develop ekagrata, the one-pointed focus of the mind (Khan ingeniously called thought "self-directed and controlled imagination"), to be aware of all the mental chatter and emotional stimuli in their body, yet not be governed by it. That is, they learn, quite literally, how to play the scales of their spine, pulling the creative energy known as kundalini from the muladhara chakra and letting it release through the sahasrara. In this way they recognize sadness, despair and suffering, as well as joy, love and equanimity, and yet are not controlled by any of them. The desire for one and denial of another fades — something the Christian-dominated heaven and hell theory needs to learn — and with their thoughts they maintain harmony at all times.

As Bob Marley sang about music, "When it hits you, you feel no pain." The music we listen to and create is a reflection of who we are. The aesthetic appreciation of the individual arises from songs that touch a chord in our hearts,that bring us deeper inside of ourselves. When one is aware of this pure sound rising both from without and within, all the illusions of ownership and suffering fade. The monochord is stretched across the cosmos, and the only tension needed is the strength and swiftness to pluck the proper strings.

Images:

- School of Athens, Rapheal

- Illustration of the Music of the Spheres, artist unknown

- Morrocan musician playing the sintir photographed by Friends of Morroco

- Hazrat Inayat Khan playing the veena

Derek Beres is one of the leading figures in international music in America, working in numerous facets of the industry, from journalist and DJ to producer and presenter. He has written for dozens of magazines covering the traditional and digital realms of global music and has toured internationally, playing alongside some of the most important figures in the scene today. In 2005 he published Global Beat Fusion: The History of the Future of Music, covering the expanding field of international music and world mythology. The book is currently being turned into a documentary film to be released in early 2007. He is currently writing his first novel, Mysterious Distance, a modern retelling of the sacrificial ritual of the Aztec corn goddess.

As DJ, Beres tours internationally with GlobeSonic Sound System, and runs New York-based EarthRise Arts with painter Craig Anthony Miller and writer Dax-Devlon Ross. He is also a Yoga Instructor and Budokon Conditioning Teacher, certified in the 200-hour teacher's certification program and Thai Yoga Massage, as well as the 200-hour Budokon teacher's program, a fusion of Hatha Yoga, Tae Kwan Do, Jujitsu and Zazen, with Kancho Cameron Shayne. He currently teaches at Equinox Fitness.

Read more by Derek Beres at his website

www.globalbeatfusion.com

Return to the Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|