|

How Gilgamesh Became the Lord of the Dead

Part Three:

Gilgamesh Journeys Through the Zodiac

by John David Ebert

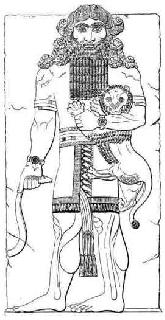

Moving onward now to a consideration of the Babylonian epic and its description of Gilgamesh's journey through the zodiac, the first point to note is that Gilgamesh and Enkidu are meant to be an incarnation of the constellation which we now refer to as Gemini. Gilgamesh was explicitly identified in a late text with the god Meslamta-ea (note the "mes" prefix) which name is the oldest known of that of the god Nergal, whose temple at Kutha was called "Emeslam." Meslamta-ea, furthermore, was one of a pair of deities whose counterpart was known as Lugal-irra, both of whom were linked astronomically with Gemini. These two gods were twins, and they were specifically associated with guarding doorways, particularly the gateway to the underworld, where they stood with bronze axes waiting to dismember the dead. When we recall the strange scene at the beginning of the epic when Gilgamesh and Enkidu first meet each other in a doorway, and then proceed to fight while somehow remaining in or near that doorway, the scene no longer appears so strange when we realize that they are meant to be the Mesopotamian Gemini who guard doorways. Both Gilgamesh and Enkidu, furthermore, like Meslamta-ea and Lugal-irra, carry bronze axes, and the first thing Enkidu does after they have felled the sacred cedar is to cut up its wood and make a doorway out of it. Moving onward now to a consideration of the Babylonian epic and its description of Gilgamesh's journey through the zodiac, the first point to note is that Gilgamesh and Enkidu are meant to be an incarnation of the constellation which we now refer to as Gemini. Gilgamesh was explicitly identified in a late text with the god Meslamta-ea (note the "mes" prefix) which name is the oldest known of that of the god Nergal, whose temple at Kutha was called "Emeslam." Meslamta-ea, furthermore, was one of a pair of deities whose counterpart was known as Lugal-irra, both of whom were linked astronomically with Gemini. These two gods were twins, and they were specifically associated with guarding doorways, particularly the gateway to the underworld, where they stood with bronze axes waiting to dismember the dead. When we recall the strange scene at the beginning of the epic when Gilgamesh and Enkidu first meet each other in a doorway, and then proceed to fight while somehow remaining in or near that doorway, the scene no longer appears so strange when we realize that they are meant to be the Mesopotamian Gemini who guard doorways. Both Gilgamesh and Enkidu, furthermore, like Meslamta-ea and Lugal-irra, carry bronze axes, and the first thing Enkidu does after they have felled the sacred cedar is to cut up its wood and make a doorway out of it.

In Roman mythology, the twins have been combined into a single figure with two faces — Janus, the god of doorways — while in Egyptian myth, the ferryman who carries souls across the threshold into the land of the dead was, like Janus, also a two-faced deity known as Her-ef-ha-ef ("he whose face is behind him.")  The Mesopotamian god Enki, moreover, the god of the watery Abzu, had a two-faced minister named Usmu often shown in attendance on him. Two-faced gods, then, or twins, are often linked with the underworld, and since we know that one of the Greek Gemini, Castor, had to die while the other became immortal, we can be reasonably certain that Gilgamesh and his mortal friend Enkidu are an early prototype of this astrological pair. The Mesopotamian god Enki, moreover, the god of the watery Abzu, had a two-faced minister named Usmu often shown in attendance on him. Two-faced gods, then, or twins, are often linked with the underworld, and since we know that one of the Greek Gemini, Castor, had to die while the other became immortal, we can be reasonably certain that Gilgamesh and his mortal friend Enkidu are an early prototype of this astrological pair.

With the image of the doorway, then, the threshold to the netherworld is laid bare, and the narrative will begin to move from the constellations of the northern celestial hemisphere to those of the southern. (With the slaying of the Taurus bull, discussed in Part II, we have already passed through the springtime equinox for the Platonic Month of the Age of Taurus. Now, in the course of Gilgamesh's solar journey through the twelve signs of the sun's annual passage through the year, we are moving forward through the ecliptic, from Taurus to Gemini to Cancer to Leo, etc. Remember, though, that with regard to the precession of the equinoxes, the "progression" moves back the other way, i.e. from the Age of Gemini to Taurus, and from the Age of Taurus [c. 4000-2000 B.C. E.] to the Age of Aries [known to the Mesopotamians, however, as the Day Laborer] [c. 2000 — 0 B.C.E.] This image of the Babylonian Gilgamesh narrative encompassing two astronomical clocks, as it were, should be held in mind, as though we were visualizing one clock, that of the precession moving backwards through the zodiac, while the other, that of the annual solar allegory, moves forwards.)

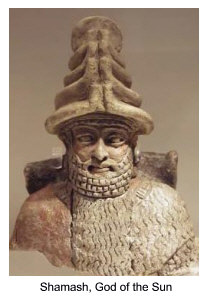

Now Enkidu is the mortal twin of the Gemini and so he is killed by a mysterious illness inflicted on him by the sun god Shamash. In Tablet VIII, the mourning speeches of Gilgamesh, in which trees and rivers and animals are said to lament the passing of Enkidu, puts us suspiciously in mind of the god Dumuzi and the later lamentations for the death of Tammuz during the summer that will become so common in the Middle East that the Arabs will name the month of July after him. If the lamentations for Enkidu are, as I suspect, deliberately meant to put us in mind of Dumuzi, then we become aware that the narrative at this point has shifted from the springtime Sacred Marriage ceremony (together with its ritual slaying of the bull) to the withering heat of summer, when the sun dries up all the vegetation of Sumer. This is perhaps why it is specifically the sun god Shamash who kills Enkidu, just as in the Samson story of the Old Testament. Samson's role as the sun god who destroys the crops in summer is dramatized by the episode in which he ties firebrands to the tails of foxes and has them run through the fields setting fire to all the crops. Now Enkidu is the mortal twin of the Gemini and so he is killed by a mysterious illness inflicted on him by the sun god Shamash. In Tablet VIII, the mourning speeches of Gilgamesh, in which trees and rivers and animals are said to lament the passing of Enkidu, puts us suspiciously in mind of the god Dumuzi and the later lamentations for the death of Tammuz during the summer that will become so common in the Middle East that the Arabs will name the month of July after him. If the lamentations for Enkidu are, as I suspect, deliberately meant to put us in mind of Dumuzi, then we become aware that the narrative at this point has shifted from the springtime Sacred Marriage ceremony (together with its ritual slaying of the bull) to the withering heat of summer, when the sun dries up all the vegetation of Sumer. This is perhaps why it is specifically the sun god Shamash who kills Enkidu, just as in the Samson story of the Old Testament. Samson's role as the sun god who destroys the crops in summer is dramatized by the episode in which he ties firebrands to the tails of foxes and has them run through the fields setting fire to all the crops.

The death of Enkidu would thus occur at about the time of Cancer — which sign, however, was known to the Sumerians not as a crab, but as the Carpenter — and in fact, Enkidu, as we have seen, is a sort of carpenter, for he is a builder of doorways. He even has a deathbed conversation with the doorway that he built for Enlil's temple in Nippur. In the earliest version of his death as recounted in the story of Gilgamesh and the huluppu tree, Gilgamesh bemoans the loss of his pukku and mikku after they have fallen into the underworld, saying: "On this day, if only my ball had stayed for me in the carpenter's workshop! O carpenter's wife, like a mother to me! If only it had stayed there!" Hertha Von Dechend, in Hamlet's Mill, suspects a reference here to the sign of the Carpenter, and we note that the events of that story take place on the day of Enkidu's death, so it would make sense if the Babylonians had retained a tradition from the Sumerians that Enkidu had died in summer under the sign of Cancer, the summer solstice point for the month of Aries into which Gilgamesh was preparing Mesopotamian civilization to enter.

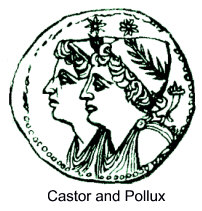

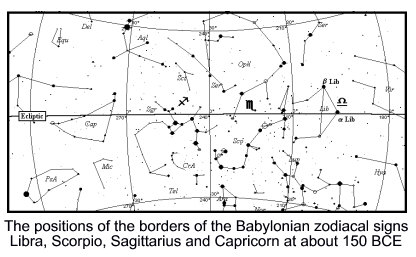

The first thing Gilgamesh does after he buries Enkidu and sets off on his wanderings is to kill a pair of lions, and so we should not be surprised to find that the Mesopotamian sign for Leo was represented as a man killing a lion. After Gilgamesh performs this deed, he puts on the lion skins — like Heracles — and eats their flesh. Then, as the text says, strangely, "Gilgamesh [dug] wells that never existed before," earning him one of his epithets as "well-digger." The digging of wells in Mesopotamian ritual is always associated with opening up portals to the underworld, and so it is appropriate that immediately after the lion sequence, he comes to the Mashu (i.e. "twin") mountains of the East, where he encounters a scorpion man and his wife guarding the gate. Now, at first glance, we would be tempted to think that these figures represent Scorpio, but it is more likely that the scorpion people represent Libra, since according to Robert Graves, one of the two scorpion people later became that constellation. (For the ancient Greeks, these two constellations, Scorpio and Libra, were not separate but rather constituted one large constellation, for the Greeks referred to Libra as the Claws of the Scorpion, not the scales). The first thing Gilgamesh does after he buries Enkidu and sets off on his wanderings is to kill a pair of lions, and so we should not be surprised to find that the Mesopotamian sign for Leo was represented as a man killing a lion. After Gilgamesh performs this deed, he puts on the lion skins — like Heracles — and eats their flesh. Then, as the text says, strangely, "Gilgamesh [dug] wells that never existed before," earning him one of his epithets as "well-digger." The digging of wells in Mesopotamian ritual is always associated with opening up portals to the underworld, and so it is appropriate that immediately after the lion sequence, he comes to the Mashu (i.e. "twin") mountains of the East, where he encounters a scorpion man and his wife guarding the gate. Now, at first glance, we would be tempted to think that these figures represent Scorpio, but it is more likely that the scorpion people represent Libra, since according to Robert Graves, one of the two scorpion people later became that constellation. (For the ancient Greeks, these two constellations, Scorpio and Libra, were not separate but rather constituted one large constellation, for the Greeks referred to Libra as the Claws of the Scorpion, not the scales).

Gilgamesh at this point goes through a dark tunnel and comes out the other side into a garden of jewels and precious stones. At the point along the ecliptic between Scorpio and Sagittarius, there is an opening to the Milky Way, and so it is possible that this tunnel leads him down to the celestial underworld where he will find this very river that will take him to the domain of Utnapishtim. Here he leaves behind the constellations of the northern hemisphere for, as the text says, "he took the path of the sun God," meaning that he followed the ecliptic as it led him down into the southern celestial hemisphere. After the jewel garden, he comes to an ocean (and now here is the Milky Way, accessible at this point from Scorpio) where a tavern is kept by a woman at the edge of the sea known as Siduri. Von Dechend has pointed out that this may be the Mesopotamian scorpion goddess Ishkhara, for in many cultures all over the world a scorpion goddess is imagined in this constellation.  "In Nicaragua and Honduras, Mother Scorpion, who dwells at the end of the Milky Way,' is described as many breasted," she writes, for the souls of the dead are supposed to be nourished by the milk from her breasts. Ishkhara, furthermore, was the Mesopotamian sign of Scorpio, and it was her job to nourish the souls of the dead from her many breasts. The milk from her breasts has here been transposed euphemistically into beer served from a tavern by a maiden (just as in Germanic myth, the souls of the dead spend their first night in a tavern governed by Gertrude). The Mesopotamians were also fond of puns, and so we note that the word for "barmaid" that is used to refer to Siduri is sabitu, a homophone for Sebittu, the Seven Sages of whom it was said that Ishkhara was their mother. "In Nicaragua and Honduras, Mother Scorpion, who dwells at the end of the Milky Way,' is described as many breasted," she writes, for the souls of the dead are supposed to be nourished by the milk from her breasts. Ishkhara, furthermore, was the Mesopotamian sign of Scorpio, and it was her job to nourish the souls of the dead from her many breasts. The milk from her breasts has here been transposed euphemistically into beer served from a tavern by a maiden (just as in Germanic myth, the souls of the dead spend their first night in a tavern governed by Gertrude). The Mesopotamians were also fond of puns, and so we note that the word for "barmaid" that is used to refer to Siduri is sabitu, a homophone for Sebittu, the Seven Sages of whom it was said that Ishkhara was their mother.

So Gilgamesh is now well on his way to the Underworld. Though there is no explicit reference at this point to Sagittarius, the centaur — known to the Mesopotamians as Pabilsag, the huntsman — I note that when Siduri first lays eyes on Gilgamesh, she sees him coming from a distance and says to herself: "For sure this man is a hunter of wild bulls," and later, when Gilgamesh is summarizing his adventures for Utnapishtim, he says, "I had yet to reach the tavern keeper, my clothing was worn out. / I killed bear, hyena, lion, panther, cheetah, / deer, ibex, the beasts and game of the wild: / I ate their flesh, their pelts I flayed." So, though there is no reference to a centaur in the story, Pabilsag was a hunter of wild animals, and it would appear that Gilgamesh momentarily steps into his role. (And besides, Gilgamesh wearing all of his various animal skins is a half-animal, half-human being, a sort of modified centaur).

Thus, Gilgamesh, traveling along the ecliptic, has reached the cluster of constellations — Libra, Scorpio and Sagittarius (the Scorpion Men, Siduri / Ishhara and Pabilsag [whose tail was depicted as that of a scorpion's]) — which mark the entrance into the southern celestial hemisphere and, in terms of the cycle of the year, the threshold point at which the days and the nights are of equal length. From now onward the nights will begin to become longer than the days, and so the abyssal side of life will begin to take precedence over the light side. In Greek mythology, correspondingly, it is at this point that Scorpio rising out of the East will sting the huntsman Orion sinking directly across the sky from him into the Western horizon. Gilgamesh, that is to say, has been stung symbolically, and now he waits at the shore of the Milky Way between Scorpio and Sagittarius for passage across the sea.

It is at this point in the sky that the ecliptic cuts across the Milky Way at an almost perpendicular angle, and in order for Gilgamesh to continue on his path through the ecliptic, he must cross the Milky Way. Siduri says to him:

Only Shamash the hero crosses the ocean: Only Shamash the hero crosses the ocean:

Apart from the sun god, who crosses the ocean?

The crossing is perilous, its way full of hazard,

And midway lie the Waters of Death, blocking the passage forward.

So, besides, Gilgamesh, once you have crossed the ocean,

When you reach the Waters of Death, what then will you do?

She then directs him to Urshanabi, who, besides being Utnapishtim's private boatman undoubtedly spends the majority of his time traveling up and down the Milky Way ferrying the souls of the dead between the northern and southern hemispheres.

Urshanabi at this point takes him out over the ocean to the domain of Utnapishtim. It was traditional in Sumerian myth that the flood survivor (originally Ziusudra) was borne by the gods to the island of Dilmun, located in the Persian Gulf as a sort of Elysium. Scholars tend to agree that Dilmun was not just a mythical land but a real place, and was most likely the island of Bahrein. Dilmun was regarded by the Sumerians as a land of fabulous wealth, and a great trade economy was established between it and the various cities of Mesopotamia. But if Dilmun was Bahrein, it was also a special place, for it was the one place in the Persian Gulf where there were abundant freshwater springs both on and around the island. There is some evidence that these springs were regarded as holy places sacred to the god Inzak, the son of Enki, Lord of the watery Abzu. Thus, Dilmun may have been thought of as a kind of source land for the waters of the Abzu, a place of eternal springs whose fresh waters emerged mysteriously from cracks in the earth. It might also have been thought that the waters conferred eternal youth on those who drank from them. The thousands of burial mounds that ripple across the deserts of the island may be evidence that Dilmun was thought to be a particularly holy place to be buried, since such a location at the nexus of Time and Eternity might have been thought to put one in the province of special powers of revivification via the island's eternal freshwater springs.

The other special thing about Dilmun was that it was a major source for pearls. To this day, pearl divers still jump from their boats off the coast of Bahrein with one rope tied around their ankles exactly as Gilgamesh is described as doing when he goes searching for the plant of eternal youth. And since we know that in folklore, pearls are regarded as having the magical property of restoring youth, it is very likely that the plant which Utnapishtim sends him diving after is not a plant at all but a pearl. In support of this notion, the archaeologist Geoffrey Bibby in his book Looking for Dilmun wrote about unearthing some pots on Bahrein inside of which the remains of serpents were found with a single pearl lodged into their mouths. And when we recall that the fate of Gilgamesh's plant was to have been snapped up by a serpent, the suspicion that Gilgamesh was really diving for a pearl becomes even stronger.

But then if Gilgamesh really has arrived at Dilmun (or Bahrein), then we must confess that the story is really working on two levels simultaneously: there is the celestial allegory of a journey through the zodiac, but apparently, Gilgamesh has also been traveling on the geographical plane south from the city of Uruk down to the headwaters of the Persian Gulf, where Urshanabi has picked him up and begun to carry him across the Gulf waters to Bahrein.

Either way, we have arrived at the domain of Utnapishtim, who appears to have been a guardian of the sacred wells upon the island of Bahrein. In this role, it is not hard to see him as Aquarius, the water bearer, who was perhaps guarding not only the island's necropolis, but may also have been the ministering priest of some sort of special baptismal rite. This would certainly be consistent with his role in the story of the great flood, which he now proceeds to recount to Gilgamesh (perhaps from the cool interior of his palm frond house with its floor made of crushed seashells). In doing so, the Babylonian editors have miniaturized an older text known as "Atrahasis," a recounting of the flood myth dating from about the same time as the Old Babylonian version of Gilgamesh (the corresponding tablet, XI, which would have recounted the Utnapishtim story in the Old Babylonian version has been lost, so we must rely on the much later Standard version). In combining the "Atrahasis" with the Sumerian Gilgamesh stories, the Babylonian editors have made their astronomical allegory more clear. This part of the text, Tablet XI, corresponds to the last three signs of the zodiac: Aquarius, Capricorn and Pisces, and this would have been necessary in order to complete their zodiacal allegory.

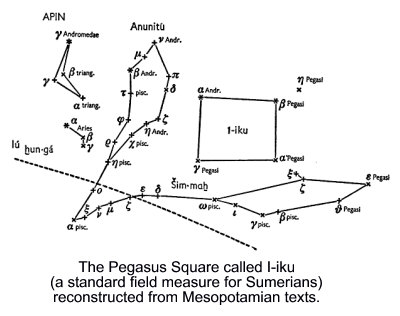

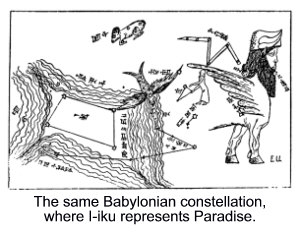

Aquarius, as I have suggested, corresponds to Utnapishtim, and Aquarius was the sign for the winter solstice during the Platonic month of Taurus, but now in the Age of Aries, the new winter solstice point will become Capricorn, the goat-fish. The god Enki is the most important of the deities in the flood myth, for he is the one who specifically warns Utnapishtim of the coming of the flood, and it is precisely this god who later became the sign of Capricorn, for both the goat and the fish were sacred to him. As Utnapishtim recounts the story of the flood to Gilgamesh, he tells him that Enki warned him that Enlil planned to destroy humanity and that Utnapishtim should build an ark shaped exactly like a cube ("her length and breadth shall be the same"). This is a strange detail until we realize that for the Mesopotamians the constellation of Pisces included the so-called Pegasus Square between the two fish, and that this square was known as "1 Iku," precisely the dimensions of the ark (an iku was a unit of measurement equivalent to 3600 square meters). The Mesopotamian constellation of Pisces, furthermore, included three other components: the Tail, the Swallow and Anunitu, the birth-goddess. With the exception of the Tail, the other two elements of Pisces do figure prominently in the flood narrative as Utnapishtim recounts it, for when the ark lands atop the mountain, the first thing Utnapishtim does is to send out three birds to find land: a dove, a swallow and a raven. The swallow, along with the other two birds, is thus associated with inaugurating a new post-diluvial World Age, just as Pisces, at the very end of the zodiac, is the last sign before the springtime equinox, at which point the Mesopotamians celebrated their New Year festival. The fourth and final component of the Mesopotamian constellation of Pisces was the birth goddess Anunitu, who in the narrative appears as Belet-ili, the birth goddess who laments over Enlil's murderous destruction of humanity.

Placing the flood myth inside the Gilgamesh narrative was the key element in completing the astronomical allegory of Gilgamesh's journey through the zodiac, an element that, we might add, could not have been present in the various scattered Sumerian fragments, since they do not form a cohesive whole. The Babylonians, therefore, and not the Sumerians, imagined the journeys of Gilgamesh as a complete circuit of the ecliptic from the stars of the northern hemisphere to those of the southern, and therefore it was they, and not the Sumerians, who universalized him by linking him with a cosmological process that could be clearly identified in any Mesopotamian city.

The only sign of the zodiac that does not occur in the story — unless I have missed it — is that of Aries, the Day-Laborer or Hired Man. However, I find the absence of this sign curious in light of the fact that it is precisely the epoch that Gilgamesh is preparing the Mesopotamians to enter. He makes a complete circuit of the ecliptic beginning with Taurus and going all the way down through Pisces, ending at precisely the last sign before Aries. Also, in terms of the precession of the equinoxes, which moves in the opposite direction of the sun's annual path, the narrative begins with the Age of Gemini in the Cedar Forest, then moves "forward" into the Age of Taurus with the Bull of Heaven episode, then stops on the cusp of Aries and moves back to Gemini with the death of Enkidu, from whence it proceeds forward to Cancer and the rest of the zodiac. The only sign of the zodiac that does not occur in the story — unless I have missed it — is that of Aries, the Day-Laborer or Hired Man. However, I find the absence of this sign curious in light of the fact that it is precisely the epoch that Gilgamesh is preparing the Mesopotamians to enter. He makes a complete circuit of the ecliptic beginning with Taurus and going all the way down through Pisces, ending at precisely the last sign before Aries. Also, in terms of the precession of the equinoxes, which moves in the opposite direction of the sun's annual path, the narrative begins with the Age of Gemini in the Cedar Forest, then moves "forward" into the Age of Taurus with the Bull of Heaven episode, then stops on the cusp of Aries and moves back to Gemini with the death of Enkidu, from whence it proceeds forward to Cancer and the rest of the zodiac.

There is at least one other curious detail worth pointing out. In the Epic, the god Enki refers to Utnapishtim as the "son of Ubar-Tutu." Turning to a document known as the Sumerian King List, we note that Ubartutu was the last king who ruled before the coming of the flood. After the flood, kingship descends from heaven for a second time, and a new cycle begins of kings who live much shorter lives (approximately 1000 years on average instead of tens of thousands each). But if we count the number of years from the time of the flood until the reign of Gilgamesh, we arrive at the interesting number of 26,554 years, which is just 634 years more than the number associated with a complete cycle of the precession of the equinoxes, namely, 25,920 years. But the difference becomes even more negligible if we suppose that the Sumerians, instead of estimating the length of each Platonic Month at 2,160 years, simply rounded it up to 2,200 years and then multiplied that by 12 to get the number 26,400, which is only 154 years less than 26,554. Either way, it becomes suspicious that Gilgamesh, a man who travels through 11 signs of the zodiac (on precisely 11, and not 12, tablets) lived about 26,000 years after the occurrence of the flood, when the last Great Year ended. This would bring the epoch in which he was living, that of Aries, back full circle to where it was in the time of Utnapishtim which, likewise, must have been Aries. This would make the time in which Gilgamesh was living the ending of another Great Year, not just of Taurus merely, and so perhaps Gilgamesh is the human being elected by the gods at the end of this mahayuga to become immortal, like Utnapishtim at the end of the previous Great Year (although Utnapishtim was never worshipped as a god).

The gods, that is to say, have elected Gilgamesh to become the Lord of the Dead because he has been initiated into the cosmic mysteries. He has completed an initiatory journey through the cosmos, in which he has witnessed secrets and caught glimpses of the great powers framing the edges of the cosmos that no human being before him had ever seen, thus rendering him fit to occupy the office of a god. His quest for immortality, then, can in no way be regarded as a failure. Even the apparent failure of the plant of ever-lasting youth that is gobbled up by the serpent has the feel of a sense of fulfillment about it, as though some secret ritual purpose were being completed unbeknownst to Gilgamesh. Such is implied by Bibby's excavations on Bahrein which have revealed buried serpents with pearls in their mouths, for this suggests that Gilgamesh's apparent failure was really part of the performance of a pre-existent myth of some sort, now lost to us. For Gilgamesh, too, in shuffling off his mortal coil upon his descent to the realm of the netherworld to become a god is imitating the powers of the snake who sloughs his skin and yet becomes immortal through the imbibed power of the pearl.

In order to become the Lord of the Dead, Gilgamesh has to know the hidden secrets of the cosmos and participate in its esoteric mysteries. Thus, the poem has the feel of an initiatic Mystery Play about it. A similar pattern is evident in the Esthonian epic known as the Kalevipoeg, whose main hero also ends by becoming the Lord of the Dead after undergoing a series of fantastic cosmic journeys. That the Babylonian editors chose not to append the Sumerian text of "The Death of Gilgamesh" to their solar epic implies nothing more than that they assumed the ultimate fate of Gilgamesh to be too well known in order to add a coda to it. And besides, this would have disrupted their astrological symbolism of retaining precisely 11 tablets in order to imply that Gilgamesh's journey was part of an attempt to bring the twelfth into being as the dawning Age of the Day Laborer for which he was making Mesopotamian civilization ready. In order to become the Lord of the Dead, Gilgamesh has to know the hidden secrets of the cosmos and participate in its esoteric mysteries. Thus, the poem has the feel of an initiatic Mystery Play about it. A similar pattern is evident in the Esthonian epic known as the Kalevipoeg, whose main hero also ends by becoming the Lord of the Dead after undergoing a series of fantastic cosmic journeys. That the Babylonian editors chose not to append the Sumerian text of "The Death of Gilgamesh" to their solar epic implies nothing more than that they assumed the ultimate fate of Gilgamesh to be too well known in order to add a coda to it. And besides, this would have disrupted their astrological symbolism of retaining precisely 11 tablets in order to imply that Gilgamesh's journey was part of an attempt to bring the twelfth into being as the dawning Age of the Day Laborer for which he was making Mesopotamian civilization ready.

We Westerners had forgotten all this and assumed that the story told on the 11 tablets contained the whole story and did not require completion, or "fill in" on the part of the knowing reader. But the clues were there all along. We should have known better, and not allowed ourselves to become beguiled too quickly by Gilgamesh's apparent failures, for it is a well-known motif in mythology that apparent failures upon a journey are really the workings out of deeper, secret undercurrents of fate that are leading the protagonist onward to the completion of higher purposes. For those very failures, when carefully examined, turn out to have been constitutive of the inner workings of a great cosmic Destiny: How the first human being in the history of mythology underwent the agonizing humiliations necessary for the breakdown of his mortal structure and subsequent transformation into a god.

John David Ebert is a former editor for the Joseph Campbell Foundation. He wrote footnotes for Baksheesh & Brahman, Sake & Satori and The Mythic Dimension, all posthumous publications of Campbell's writings. His first book was Twilight of the Clockwork God: Conversations on Science & Spirituality at the End of an Age (Council Oak Books, 1999). His most recent book is entitled Celluloid Heroes & Mechanical Dragons: Film as the Mythology of Electronic Society (Cybereditions, 2005), and was reviewed by Dr. William Doty in the August 2005 issue of Mythic Passages. His work has been published in various periodicals such as Utne Reader, The Antioch Review, Lapis and Alexandria. He is currently working on a book about popular culture and mythology, tentatively entitled Electric Demigods of the Lightspeed World. John David Ebert is a former editor for the Joseph Campbell Foundation. He wrote footnotes for Baksheesh & Brahman, Sake & Satori and The Mythic Dimension, all posthumous publications of Campbell's writings. His first book was Twilight of the Clockwork God: Conversations on Science & Spirituality at the End of an Age (Council Oak Books, 1999). His most recent book is entitled Celluloid Heroes & Mechanical Dragons: Film as the Mythology of Electronic Society (Cybereditions, 2005), and was reviewed by Dr. William Doty in the August 2005 issue of Mythic Passages. His work has been published in various periodicals such as Utne Reader, The Antioch Review, Lapis and Alexandria. He is currently working on a book about popular culture and mythology, tentatively entitled Electric Demigods of the Lightspeed World.

Read more by John Ebert at his website cinemadiscourse.com

Return to the Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|