|

Chapter One

Chapter One

A Moth to the Flame:

The Life of the Sufi Poet Rumi

by Connie Zweig

© 2007

Roman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. and used with permission

Connie Zweig, Ph.D., a therapist in private practice in Los Angeles, has been a student of the mystical teachings and practices of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism for more than thirty years. Former columnist for Esquire and contributor to the Los Angeles Times, she is co-author of the best-selling Meeting the Shadow and Romancing the Shadow. Her work on illuminating the dark side of human nature has been featured nationwide and translated into ten languages. She is also author of The Holy Longing: The Hidden Power of Spiritual Yearning, which explores the psychology of religious/spiritual aspiration and the shadow side of religious life. She has taught around the country about human spirituality, religious abuse and disillusionment. A Moth to the Flame is her first novel. It is the inner story of holy longing as lived by Sufi poet Jelaluddin Rumi.

-

-

From my first breath I have longed for Him —

This longing has become my life.

1231 A.D.

Konya, Turkey

Pacing at the edge of the garden, his eyes burning, his lower lip trembling, he knows when he goes back inside his old life will be over. Dread surges into his mouth like a tart lemon, leaving it puckered and dry. Trudging back and forth in the chill to avoid the moment as long as he can, he shivers as the caftan flaps at his ankles and his sandals crunch the dirt.

Above him in the blackness, a comet shoots across the silver-dotted sky. A bad omen?

His stomach lurches when he notices that the red tulips, so loved by his father, have wilted. The queasiness passes and he begins pacing again, rubbing his palms together for warmth. But the wetness is seeping into the caftan now. He stops in his tracks, braces himself, and steps across the threshold into the house.

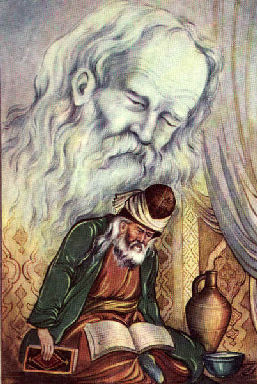

Pushing aside the curtain to his father's room, he peers in, and his stomach turns over again. The turbaned head of Bahaoddin rests on a worn, blue cushion. His beard, white with eighty snows, rests on his chest. He is lying still, his bronze face yellowed, his black eyes vacant, only his lips moving, murmuring the names of God.

Bending down over the patient to sniff his breath, the doctor seems troubled. Several days earlier, he had prescribed bitter wood to improve appetite and anise to improve digestion. But Bahaoddin refused both. Now, the doctor urges his patient, "Master, rest for just a few minutes. You can return to your practices soon."

His father arouses himself to reply. "All that I have gained is the result of these practices. I won't abandon them now." After nodding, the doctor exits the room.

As he moves closer to his father and folds his legs on the floor beside him, the women's voices in their quarters rise to a pitch, petitioning God to save the Master. He imagines them blowing on knots to appease the evil eye and mixing vinegar with the nectar of the hive to feed their sheikh.

A moment later, he hears a steed stomping outside the house. The sultan, bedecked in orange robes and gold earrings, hurries into the room and kneels low. "Master, Konya will not be the same without you." A moment later, he hears a steed stomping outside the house. The sultan, bedecked in orange robes and gold earrings, hurries into the room and kneels low. "Master, Konya will not be the same without you."

"Don't be sad, sultan," Bahaoddin says in a hushed tone. "We come from God, and to God we go home. This is the great return, and you will follow me soon." Appearing frightened, the ruler scurries out.

Finally, his father turns his head toward him. "Before you came back, son, I had a dream. Like prayers, dreams are conversations with the Holy One, who knows the future. In mine, there was a sultan, whose head was made of gold. His breast was made of silver, his body of bronze, his thighs of lead, his feet of pewter. As long as he was there, the people were as precious as gold. In the son's reign, they would be as precious as silver. After him, they would have the value of bronze."

The Master coughs, his chest rattling. He forces the words out, "Then a great disorder will arise. No sincerity, no faith in the fourth generation. By the fifth, the dynasty will decline, and the Mongols will conquer the land."

The images chill him, as if he remains out in the night air. "But father, if we fight. . . ."

"Shhhhh. . . .The Brothers' safety from the Mongol hordes is in your hands now, son. Keep the people as precious as gold for as long as you can. Time is short."

His father reaches beneath the carpets, pulling out a stack of papers that is bound between wooden boards. "You will need my teachings. Now they are yours," he murmurs, handing them over.

Choking back tears, he glances down — The Divine Sciences by Bahaoddin Velad — and clutches the precious pages to his heart.

"And the final secret," Bahaoddin says under his breath. "Come closer." His father pulls the edge of his robe and draws him in, their beards touching, hot breath falling on his ear.

The words startle him. How does father know this?

Then Bahaoddin mutters, "In these terrible times, may God guide you on the path to Him as you guide our dervish Brothers."

A scream rises up in him. No! Don't leave me, father. Mother is gone, not you too.

He quickly swallows the scream, blinks back tears, and opens the pages of the book to distract himself. The curves and loops of the script seem to shine. What of the hidden meanings and secret names that you have not told me? Are they here, on these pages, or will they die with you?

His father's throat rattles. It's no time to read. As he sets the book aside, his glance returns to Bahaoddin.

The old man's skin, once smooth as an urn, is creased and furrowed now. His hollow eyes, looking weary, slowly withdraw. The names of God grow fainter on his lips and finally cease altogether. Silence.

A wave of grief rolls through him, threatening to overtake him, as he turns his father's turbaned head toward Mecca, preparing him for resurrection on judgment day. Then he hears himself say, "There is no god but God."

An instant before, he was a son, a disciple. Now he is alone. He can no longer look up into Bahaoddin's wise, fearless face. He can no longer pose any question and expect to be escorted through the arguments until he knows the correct response. For the first time, he is without a true friend, without a guide.

The grief gives way to shock and terror as he stands up to leave the room. His mind is racing. How could this have happened? I am only twenty-four, not ready to be the leader of the people, the only link in a chain of teachers going back to the Prophet.

© Shahriar Shahriari 1998, Vancouver Canada, 1999 - 2005, Los Angeles, CA

www.rumionfire.com/gallery/pic06.htm

Image from Wikipedia

After the family and disciples bid farewell to the Master, he watches the Brothers wash the body, stuff the ears, nose, and mouth with cotton, tie the ankles together, rest the hands on the chest, and wrap his father in a linen shroud. As they carry the corpse on a bier past shops and mosques, the people of Konya, rich and poor, Muslim and Christian, follow in procession, their heads uncovered. Tearing their robes to shreds until their bodies are nearly bare, they cry out verses from the Koran, the psalms, the gospels. The muezzin's rising chants fill the air with song as his heart wells up with grief.

Arriving at the grave in the rose garden, the Brothers set down the bier on the earth, and he moves forward tentatively, out of the crowd. Just then, a distraught disciple throws himself on the bier, shouting, "I'm going with you. I want to enter paradise with you, Master."

His heart aches for the man and he knows exactly what he feels. He too has lost his direction and wants only, for this instant, to join his father in paradise, to be embraced in the arms of Allah.

But it is his job now to comfort the Brothers, to offer them guidance, to explain their larger purpose. I must find a way to be strong for them now. With God's help, I must.

With the others watching him, he links his arm through the man's arm and lifts him up to standing, saying, a bit meekly, "Have a passion for life, not death, Brother."

But his heart resists his own words, demanding, What is there to live for without the loving presence of my father?

No, he must shake off the hopelessness for the sake of the believers. He continues, "Instead of following death, Brothers, enter the greater life. Marry your own soul, as my father did. That is our deeper purpose." And he knows in that moment that he speaks as much to himself as to the grieving disciple.

Following the funeral, he remains by the tomb as distraught dervishes in blue robes, mouthing prayers and shedding tears, gather among the red and yellow roses. Men stroke the circular stone and its conical cap with long fingers, praying for the Master's intercession in their lives. Scarved women kneel and sob gently, leaving bundles of halva in exchange for wishes granted. A young girl places a yellow rose against the stone. Finally, only he is left standing. Alone.

The next afternoon, as the sun rolls overhead, he drapes himself in his father's black robe with the wide sleeves, the gown of a scholar. And he makes his way up the hill toward the great mosque as if for the first time. Below him, off to one side, green fields of lettuce and strawberries stretch as far as he can see. Off to the other, golden grains of wheat sway in the breeze. The silver dome covers the rectangular building like the dome of heaven itself. Long-necked white storks nest in the two silver minarets, which soar high into the blue sky. Slipping off his shoes, he crosses the threshold.

Inside, thick, carved marble columns support arched passageways. A wooden stairway carved with linking lines that form stars leads to the pulpit, inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Flaming red carpets cover the floors between the pillars.

As he steps up to the pulpit, four Koran reciters surround him, and the people seated before him now believe that the Prophet Mohammed, blessed be he, addresses them today through him, their sheikh. And yet. . . .

He may be intellectually prepared, having studied the Koran and the intricacies of Muslim law. He has read widely in philosophy — Ghazzali who, paralyzed and mute from a loss of faith, claimed that practices, not theological arguments, would fulfill the promise of religion. Suhrawardi, who urged believers to make a symbolic, not a literal reading of the Koran. And Ibn 'Arabi in Spain, who proclaimed that each individual is a unique expression of a divine attribute of God.

Besides Persian, he speaks Arabic and Turkish. He knows how to work with numerals and to recognize Capricorn, the mountain goat, and Sagittarius, the archer with the long tail of a dragon, in the night skies. But what does it all add up to?

His father, wise in the hidden meanings, passed on only a few secrets to him. Spiritually, he is unprepared, a novice. He has knowledge of Sufism, but not experience. He knows about God, but he has not seen Him face to face.

Setting his hands firmly on his father's worn copy of the Koran, he surveys the sea of eager faces: the sultan in a red gown with the weaver, butcher, candle maker, tanner, perfume seller, and stonecutter in threadbare robes. Some men bow their heads and move their lips in constant zikhr. Clustered in the rear, women in headscarves pulled across their mouths begin to sway back and forth in silence. A neighboring sheik in a coiled, green turban sits beside a Christian monk, who hides his light skin in a black cowl. The Jewish wine seller is bare-headed. And an adolescent boy in billowing white robes, oblivious of the crowd, wanders up and down between the pillars, grinning at something the others cannot see.

As hundreds of eyes bore through his robe, he feels naked. His father no longer stands between him and the peoples' great hunger. He draws a breath and does the only thing he can do, the duty that is required of him at this moment: he praises God, blesses the Prophet, offers blessings to the sultan, and begins his first discourse as the sheikh.

"Brothers," he begins, "why do we open each prayer with a negation? 'There is no God,' we say, 'but God,' we affirm. We negate the world, then we affirm the existence of God."

The power of mystery seems to enter the room, and he is encouraged to go on, a bit louder. "Don't listen to these words. Listen behind them. Words are a shadow of reality. A resonance draws one man to another, not words. If a man sees a thousand miracles but there is no resonance connecting him with that sheikh, then those phenomena will be profitless."

He pauses, regarding his listeners. "If there is no amber in a straw, the straw will not move toward amber. If there is no resonance in a man, he will not move toward a sheikh."

He clears his throat. He has known these truths for so long that the words ring hollow to him. His tongue feels thick. As he studies the people, a few glare at him like an idol, a dazzling peacock to adore. For an instant, his chest puffs up. Yes, my mind is quicker than theirs, my heart more faithful.

Then, after pausing, he comes back to himself. No, I will not accept their worship. I am merely their guide, their caravan leader. I will teach them to see things as they are, not as they appear.

But this knowledge and position are not enough for him. Even the sacred law, the Shari'a, ablutions, prayers, alms, and fasting do not satisfy his hunger. Even here, in this house of prayer, a restless yearning is arising again, gnawing at him, demanding something more from life, more than this traditional outer form.

What is this longing that calls me away from my duty, this restlessness that gives me no peace? I will go through the motions, but one day I will have to heed the call. I will have to turn toward what I most deeply love, in spite of any danger, any risk.

He reins in his impatience and attends to his followers. "Every thing other than God is leading you astray, be it your throne, kingdom, or crown. The world's harp has but a single string."

An expectant hush comes over the crowd. Some stare up at him, rapture on their faces. Others hang their heads, weeping with reassurance. Even the restless children are quieted. With this sermon, the hundreds of disciples of his father are now devoted to him.

From this day forward he is called Rumi, named after Rum, the land of Roman Anatolia in south central Turkey on which he stands. He wraps himself in the new name, and it settles on his shoulders like a cloak. It ties him to the land, its fortunes, and its fate. He is no longer Jelaloddin of Balkh. He is the sheikh of Rum.

But in his inmost heart, he longs for something more. And this gnawing feeling leaves him restless and thirsty.

This material is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Please contact the publisher for permission to copy, distribute or reprint.

Read more about Connie Zweig at her website www.conniezweig.com

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|