|

"Myth and Ritual"

An Excerpt from Myth: A Very Short Introduction

By Robert A. Segal

© 2007 Oxford University Press, used by permission

Myth is commonly taken to be words, often in the form of a story. A myth is read or heard. It says something. Yet there is an approach to myth that deems this view of myth artificial. According to the myth and ritual, or myth-ritualist, theory, myth does not stand by itself but is tied to ritual. Myth is no just a statement but an action. The least compromising form of the theory maintains that all myths have accompanying rituals and all rituals accompanying myths. In tamer versions some myths may flourish without rituals or some rituals without myths. Alternately, myths and rituals may originally operate together but subsequently go their separate ways. Or myths and rituals may arise separately but subsequently coalesce. Whatever the tie between myth and ritual, the myth-ritualist theory differs from other theories of myth and from other theories of ritual in focusing on the tie.

William Robertson Smith William Robertson Smith

The myth-ritualist theory was pioneered by the Scottish Biblicist and Arabist William Robertson Smith (1846 — 1894). In his Lectures on the Religion of the Semites Smith argues that belief is central to modern religion but not to ancient religion, in which ritual was central. Smith grants that ancients doubtless performed rituals only for some reason. But the reason was secondary and could even fluctuate. And rather than a formal declaration of belief, or a creed, the reason was a story, or a myth, which simply described the circumstances under which the rite first came to be established by the command or by the direct example of the god. Smith argues that belief is central to modern religion but not to ancient religion, in which ritual was central. Smith grants that ancients doubtless performed rituals only for some reason. But the reason was secondary and could even fluctuate. And rather than a formal declaration of belief, or a creed, the reason was a story, or a myth, which simply described the circumstances under which the rite first came to be established by the command or by the direct example of the god.

Myth itself was "secondary". Where ritual was obligatory, myth was optional. Where ritual was set, any myth would do. And myth did not even arise until the original, non-mythic reason given for the ritual had somehow been forgotten:

... [T]he myth is merely the explanation of a religious usage; and ordinarily it is such an explanation as could not have arisen till the original sense of the usage had more or less fallen into oblivion.

(Smith, Lectures on the Religion of the Semites, p 19)

While Smith was the first to argue that myths must be understood vis-à-vis rituals, the nexus by no means requires that myths and rituals be of equal importance. For Smith, there would never have been myth without ritual, whether or not without myth there would have ceased to be ritual.

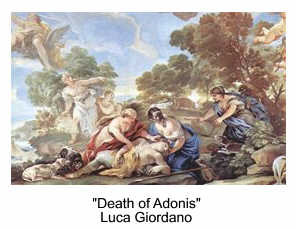

Because Adonis was a Semite god, Smith includes him in his Lectures. As part of his overall argument that ancient religion had no sense of sin, so that sacrifice — the main ritual — was not penance, he contrasts the amoral, mythic explanation for the ritualistic 'wailing and lamentation' over the dead Adonis to the later, 'Christian idea that the death of the God-man is a death for the sins of the people': Because Adonis was a Semite god, Smith includes him in his Lectures. As part of his overall argument that ancient religion had no sense of sin, so that sacrifice — the main ritual — was not penance, he contrasts the amoral, mythic explanation for the ritualistic 'wailing and lamentation' over the dead Adonis to the later, 'Christian idea that the death of the God-man is a death for the sins of the people':

[I]f, as in the Adonis myth, an attempt is made to give some further account of the annual rite than is supplied by the story that the god had once been killed and rose again, the explanation offered is derived from the physical decay and regeneration of nature. The Canaanite Adonis or Tammuz ... was regarded by his worshippers as the source of all natural growth and fertility. His death therefore meant a temporary suspension of the life of nature ... And this death of the life of nature the worshippers lament out of natural sympathy without any moral idea, just as modern man is touched with melancholy at the falling of the autumn leaves.

(Smith, Lectures on the Religion of the Semites, p 19)

In other words, originally, there was just the ritualistic sacrifice of the god Adonis, plus whatever non-mythic reason was given for it. That ritual involved not only the killing but also the mourning and, too, the hope for Adonis' rebirth. Once the reason for the ritual was forgotten, the myth of Adonis as the dying and rising god of vegetation was created to account for the ritual. As pagan rather than Christian, the myth did no judge the killing sinful.

One major limitation of Smith's theory is that it explains only myth and not ritual, which is simply presupposed. Another limitation is that the theory obviously restricts myth to ritual, though Smith does trace the subsequent development of myth independent of ritual. Yet in so far as myth as even an explanation of ritual typically involves the action of a god, myth from the start is about more than sheer ritual, as Smith himself grants.

E.B. Tylor E.B. Tylor

In claiming that myth is an explanation of ritual, Smith was denying the standard conception of myth, espoused classically by E.B. Tylor. According to Tylor, let us recall, myth is an explanation of the physical world, not of ritual, and operates independently of ritual. Myth is a statement, not an action, and amounts to a creed, merely presented in the form of a story. For Tylor, ritual is to myth as, for Smith, myth is to ritual: secondary. Where for Smith myth presupposes ritual, for Tylor ritual presupposes myth. For Tylor, myth functions to explain the world as an end in itself. Ritual applies that explanation to control the world. Ritual is the application, not the subject, of myth. The subject remains the world. Both because ritual depends on myth and, even more, because explanation is for Tylor more important than control, myth is a more important aspect of religion than ritual. Smith might as well, then, have been directing himself against Tylor in stating that "religion in primitive times was not a system of beliefs with practical applications' but instead 'a body of fixed traditional practices".

Smith is like Tylor in one key aspect. For both, myth is wholly ancient. Modern religion is without myth — and without ritual as well. Myth and ritual are not merely ancient but primitive. In fact, for both Tylor and Smith, ancient religion is but a case of primitive religion, which is the fundamental foil to modern religion. Where for Tylor modern religion is without myth and ritual because it is no longer about the physical world and is instead a combination of ethics and metaphysics, for Smith modern religion is without myth and religion because it is a combination of ethics and creed. For Tylor, modern religion, because bereft of myth, id a come-down from its ancient and primitive height. For Smith, modern religion, because severed from myth and, even more, from ritual, is a leap beyond its ancient and primitive beginnings. The epitome of modern religion for Smith is his own vigorously anti-ritualistic, because anti-Catholic, Presbyterianism. The main criticism to be made of both Tylor and Smith is their confinement of myth and ritual to ancient and primitive religion.

J.G. Frazer J.G. Frazer

In the several editions of The Golden Bough J.G. Frazer developed the myth-ritualist theory far beyond that of his friend Smith, to whom he dedicates the work. While The Golden Bough is best known for its tripartite division of all culture into the stages of magic, religion, and science, the bulk of the tome in fact concerns an intermediate stage between religion and science — a stage of magic and religion combined. Only in this in-between stage, itself still ancient and primitive, is myth-ritualism to be found, for only here do myths and rituals work together. J.G. Frazer developed the myth-ritualist theory far beyond that of his friend Smith, to whom he dedicates the work. While The Golden Bough is best known for its tripartite division of all culture into the stages of magic, religion, and science, the bulk of the tome in fact concerns an intermediate stage between religion and science — a stage of magic and religion combined. Only in this in-between stage, itself still ancient and primitive, is myth-ritualism to be found, for only here do myths and rituals work together.

Frazer, rarely consistent, actually presents two distinct versions of myth-ritualism. In the first version ... myth describes the life of the god of vegetation, the chief god of the pantheon, and ritual enacts the myth describing his death and rebirth. The ritual operates on the basis of the magical Law of Similarity, according to which the imitation of an action causes it to happen. The clearest example of this brand of magic is voodoo. The ritual directly manipulates the god of vegetation, no vegetation itself, but as the god goes, so automatically goes vegetation. That vegetation is under the direct control of a god is the legacy of religion. That vegetation can be controlled, even if only indirectly through the god, is the legacy of magic. The combination of myth and ritual is the combination of religion and magic:

Thus the old magical theory of the seasons was displaced, or rather supplemented by a religious theory. For although men now attributed the annual cycle of change primarily to corresponding changes in their deities, they still thought that by performing certain magical rites they could aid the god who was the principle of life, in his struggle with the opposing principle of death. They imagined that they could recruit his failing energies and even raise him from the dead.

(Frazer, The Golden Bough, p. 377)

The ritual is performed when one wants winter to end, presumably when stored-up provisions are running low. A human being, often the king, plays the role of the god and acts out what he thereby magically induces the god to do.

In Frazer's second, until now unmentioned, version of myth-ritualism the king is central. Here the king does not merely act the part of the god but is himself divine, by which Frazer means that the god resides in him. Just as the health of vegetation depends on the health of its god, so now the health of the god depends on the health of the king: as the king goes, so goes the god of vegetation, and so in turn goes vegetation itself. To ensure a steady supply of food, the community kills its king while he is still in his prime and thereby safely transfers the soul of the god to his successor:

For [primitives] believe ... that the king's life or spirit is so sympathetically bound up with the prosperity of the whole country that if he fell ill or grew senile the cattle would sicken and cease to multiply, the crops would rot in the fields, and men would perish of widespread disease. Hence, in their opinion, the only way of averting these calamities is to put the king to death while he is still hale and hearty, in order that the divine spirit which he has inherited from his predecessors may be transmitted in turn by him to his successor while it is still in full vigour and has not yet been impaired by the weakness of disease and old age.

(Frazer, The Golden Bough, pp. 312-13)

The king is killed either at the end of a short term or at the first sign of infirmity. As in the first version, the aim is to end winter, which now is attributed to the weakening of the king. How winter can ever, let alone annually, ensue if the king is removed at or even before the onset of debilitation, Frazer never explains.

In any event, this second version of myth-ritualism has proved the more influential by far, even though it actually provides only a tenuous link between religious myth and magical ritual. Instead of enacting the myth of the god of vegetation, the ritual simply changes the residence of the god. The king dies not in imitation of the death of the god but as a sacrifice to preserve the health of the god. What part myth plays here, it is not easy to see. Instead of reviving the god by magical imitation, the ritual revives the god by a transplant.

In Frazer's first truly myth-ritualist scenario myth arises prior to ritual rather than, as for Smith, after it. The myth that gets enacted in the combined stage emerges in the stage of religion and therefore antedates the ritual to which it is applied. In the combined stage myth, as for Smith, explains the point of the ritual, but from the outset. Myth gives ritual its original and sole meaning. Without the myth of the death and rebirth of that god, the death and rebirth of the god of vegetation would scarcely be ritualistically enacted. Still, myth for Frazer, as for Taylor, is an explanation of the world — of the course of vegetation — and not just, as for Smith, of ritual. But for Frazer, unlike Tylor, explanation is only a means to control, so that myth is the ancient and primitive counterpart to applied science rather than, as for Tylor, to scientific theory. Ritual may still be the application of myth, but myth is subordinate to ritual.

The severest limitation of Frazier's myth-ritualism is not only that it, like Smith's, precludes modern myths and rituals but also that it restricts even ancient and primitive myth-ritualism to myths about the god of vegetation, and really only to myths about the death and rebirth of the god.

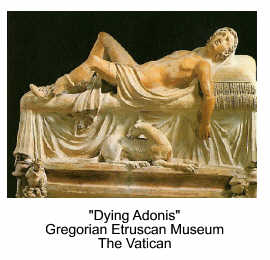

Where Smith discusses the case of Adonis only in passing, Frazer makes Adonis a key example of the myth and ritual of the dying-and-rising god of vegetation. Consistently or not, Frazer actually places Adonis in all three of his pre-scientific stages of culture: those of magic, of religion, and of magic and religion combined. Where Smith discusses the case of Adonis only in passing, Frazer makes Adonis a key example of the myth and ritual of the dying-and-rising god of vegetation. Consistently or not, Frazer actually places Adonis in all three of his pre-scientific stages of culture: those of magic, of religion, and of magic and religion combined.

Frazer locates the celebrated potted gardens of Adonis in his first magical stage. In this stage humans believe that impersonal forces rather than gods cause events in the physical world. Ancient Greeks would have been planting seeds in earth-filled pots not to persuade a god to grant growth but, by the magical Law of Similarity, to force the impersonal earth itself to grow: "For ignorant people suppose that by mimicking the effect which they desire to produce they actually help to produce it." Because there are no gods in this stage, Adonis can hardly be a god of vegetation. Rather, he is vegetation itself. Vegetation does no symbolize Adonis; Adonis symbolizes vegetation.

In Frazer's second religious stage gods replace magical laws as the sources of events in the physical world, so that Adonis becomes at least on the literal level, the god of vegetation. As the god of vegetation, Adonis could, most simply, have been asked for crops. Or the request could have been reinforced by obedience to the god's ritualistic and ethical dictates. Frazer himself writes that rites of mourning were performed for Adonis — not, as in the next stage, to undo his death but to seek his forgiveness for it. For Adonis has died not, as in the next stage, because he has descended to the Underworld, but because in cutting, stamping, and grinding the corn — the specific part of vegetation he symbolizes — humans have killed him. Rather than 'the natural decay of vegetation in general under the summer heat or winter cold', the death of Adonis is 'the violent destruction of the corn by man'. Yet Adonis is somehow still sufficiently alive to be capable of punishing humans, something that the rituals of forgiveness are intended to avert. Since, however, Adonis dies because vegetation itself dies, the god is here really as in the first stage, only a metaphor for the element that he supposedly controls. Again, as vegetation goes, so goes Adonis.

In Frazer's third, combined stage Adonis seems at last a god. If in stage two as vegetation goes, so goes Adonis, now as Adonis goes, so seemingly goes vegetation. Adonis' death means his descent to the Underworld for his stay with Persephone. Frazer assumes that, whether or not Adonis has willed his descent, he is too weak to ascend by himself. By acting out his rebirth, humans facilitate it. On the one hand the enactment employs the magical Law of Similarity. On the other hand the enactment does not, as in the first stage, compel but only bolsters Adonis, who, despite his present state of death, is yet hearty enough to revive himself, just not unassisted. In this stage gods still control the physical world, but their effect on it is automatic rather than deliberate. To enact the rebirth of Adonis is to spur his rebirth and, through it, the rebirth of vegetation.

Yet even in this stage the sole aspect of Adonis' life considered by Frazer is that which parallels the animal course of vegetation: Adonis' death and rebirth. Adonis' otherwise unnatural life, beginning with his incestuous birth, is ignored. Ignored above all is Adonis' final death, the unnatural cause — killing, even murder — aside. And so Frazer must do, [f]or if Adonis' life is to symbolize the course of vegetation, Adonis must continually die and be reborn. Yet he does not. By whatever means Adonis in Apollodorus' version overcomes death annually, he does not do so indefinitely. In Ovid's version Adonis has never before died and been reborn, and Venus is disconsolate exactly because he is gone once and for all. How, then, can his short, mortal life symbolize eternal rebirth, and how can he be a god? Frazer never says. Yet even in this stage the sole aspect of Adonis' life considered by Frazer is that which parallels the animal course of vegetation: Adonis' death and rebirth. Adonis' otherwise unnatural life, beginning with his incestuous birth, is ignored. Ignored above all is Adonis' final death, the unnatural cause — killing, even murder — aside. And so Frazer must do, [f]or if Adonis' life is to symbolize the course of vegetation, Adonis must continually die and be reborn. Yet he does not. By whatever means Adonis in Apollodorus' version overcomes death annually, he does not do so indefinitely. In Ovid's version Adonis has never before died and been reborn, and Venus is disconsolate exactly because he is gone once and for all. How, then, can his short, mortal life symbolize eternal rebirth, and how can he be a god? Frazer never says.

Finally, Frazer, once again oblivious to consistency, simultaneously declares Adonis' life in even the combined stage to be but a symbol of the course of vegetation itself: the myth that Adonis spent a portion of the year in the Underworld

... is explained most simply and naturally by supposing that he represented vegetation, especially the corn, which lies buried in the earth half the year and reappears above ground the other half.

(Frazer, The Golden Bough, p. 392)

Adonis now proves to be not the cause of the fate of vegetation but only a metaphor for that fate, so that in stage three as well as in stage two as vegetation goes, so goes Adonis, and not vice versa. How myth-ritualism is possible when there is no longer a god to be ritualistically revived and when there is only a description, not an explanation, of the course of vegetation, is not easy to see. In now taking mythology as a symbolic description of natural processes, Frazer is like a group of largely German nineteenth-century theorists know appropriately as nature mythologists.

Jane Harrison and S.H. Hooke Jane Harrison and S.H. Hooke

The next stage of the myth-ritualist theory came with Jane Harrison (1850-1928) and S.H. Hooke (1874-1968), the English leaders of the initial main group of myth-ritualists, classicists, and Biblicists. Their positions are close. Both largely follow Frazer's first myth-ritualist scheme, though Hooke, nearly as inconsistent as Frazer, sometimes follows the second scheme. Unlike Frazer, Hooke and Harrison postulate no distinct, prior stages of magic and of religion. Both begin instead with the equivalent of Frazer's combined stage. Like Frazer, they deem myth-ritualism the ancient and primitive counterpart to modern science, which replaces not only myth-ritualism but myth and ritual per se. Harrison and Hooke follow Frazer, most of all in their willingness to see heretofore elevated, superior religions — those of Hellenic Greece and of biblical Israel — as primitive. The conventional, pious view had been, and often continues to be, the Greece and Israel stood above the benighted magical endeavours of their neighbors.

Venturing beyond both Frazer and Hooke, Harrison adds to the ritual of the renewal of vegetation the ritual of initiation into society. She even argues that the original ritual, while still performed annually, was exclusively initiatory. There was no myth, so that for her, as for Smith, ritual precedes myth. God was only the projections of the euphoria produced by the ritual. Subsequently, god became the god of vegetation, the myth of death and rebirth of that god arose, and the ritual of initiation became an agricultural ritual as well. Just as the initiates symbolically died and were reborn as fully fledged members of society, so the god of vegetation and in turn crops literally died and were reborn. In time, the initiatory side of the combined ritual faded, and only the Frazerian, agricultural ritual remained.

Against Smith, Harrison and Hooke alike deny vigorously that myth is an explanation of ritual: "The myth," states Harrison "is not an attempted explanation of either facts or rites." But she and Hooke really mean no more than Frazer. Myth is still an explanation of what is presently happening in the ritual, just not of how the ritual arose. Myth is like the sound in a film or the narration of a pantomime. Writes Hooke: "In general the spoken part of a ritual consists of a description of what is being done .... This is the sense in which the term "myth" is used in our discussion." Harrison puts it pithily: "The primary meaning of myth ... is the spoken correlative of the acted rite, the thing done".

Both Harrison and Hooke go further than Frazer. Where for him the power of myth is merely dramatic, for Harrison and Hooke it is outright magical. "The spoken word," writes Hooke "had the efficacy of an act." "A myth," writes Harrison "becomes practically a story of magical intent and potency." We have here word magic.

Contemporary myth-ritualists like the American classicist George Nagy appeal to the nature of oral, as opposed to written, literature to argue that myth was originally so closely tied to ritual, or performance, as to be ritualistic itself:

Once we view myth as performance, we can see that myth itself is a form of ritual: rather than think of myth and ritual separately and only contrastively, we can see them as a continuum in which myth is a verbal aspect of ritual while ritual is a notional aspect of myth.

(Gregory Nagy, Can Myth Be Saved?, p. 243)

How this position goes beyond that of Hooke and Harrison is far from clear.

Application of the Theory

The classicists Gilbert Murray, F.M. Cornford, and A.B. Cook, all English or English-resident, applied Harrison's theory to such ancient Greek phenomena as tragedy, comedy, the Olympic Games, science, and philosophy. These seemingly secular, even anti-religious, phenomena are interpreted as latent expressions of the myth of the death and rebirth of vegetation.

Among Biblicists, the Swedish Ivan Engnell, the Welsh Aubrey Johnson, and the Norwegian Sigmund Mowinckel differed over the extent to which ancient Israel in particular adhered to the myth-ritualist pattern. Engnell sees an even stronger adherence than the cautious Hooke; Johnson and especially Mowinckel, a weaker one.

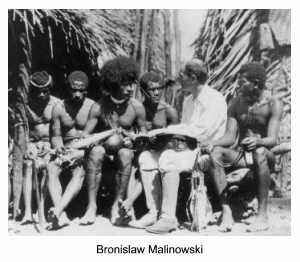

Invoking Frazer, Bronislaw Malinowski ... applied his own qualified version of the theory to the myths of native peoples worldwide. Malinowski argues that myth, which for him, as for Smith, explains the origins of ritual, gives ritual a hoary past and thereby sanctions them. Society depends on myth to spur adherence to rituals. But if all rituals depend on myth, so do many other cultural practices on which society depends. They have myths of their own. Myth and ritual are therefore not coextensive. Invoking Frazer, Bronislaw Malinowski ... applied his own qualified version of the theory to the myths of native peoples worldwide. Malinowski argues that myth, which for him, as for Smith, explains the origins of ritual, gives ritual a hoary past and thereby sanctions them. Society depends on myth to spur adherence to rituals. But if all rituals depend on myth, so do many other cultural practices on which society depends. They have myths of their own. Myth and ritual are therefore not coextensive.

Mircea Eliade ... applied a similar form of the theory, but he goes beyond Malinowski to apply the theory to modern as well as primitive cultures. Myth for him, too, sanctions phenomena of all kinds, not just rituals, by giving them a primæval origin. For him, too, then, myth and rituals are not coextensive. But Eliade again goes beyond Malinowski in stressing the importance of the ritualistic enactment of myth in the fulfillment of the ultimate function of myth: when enacted, myth acts as a time machine, carrying one back to the time of the myth and thereby bringing one closer to god.

Application of the Theory to Literature

The most notable application of the myth-ritualist theory outside of religion has been to literature. Harrison herself boldly derived all art, not just literature, from ritual. She speculated that gradually people ceased believing that the imitation of an action caused that action to occur. Yet rather than abandoning ritual, they now practiced it as an end in itself. Ritual for its own sake became art, her clearest example of which is drama. More modestly than she, Murray and Cornfield rooted specifically Greek epic, tragedy, and comedy in myth-ritualism. Murray then extended the theory to Shakespeare.

Other standard-bearers of the theory have included Jessie Weston on the Grail legend, E.M. Butler on the Faust legend, C.I. Barber on Shakespearean comedy, Herbert Weisinger on Shakespearean tragedy and on tragedy per se, Francis Fergusson on tragedy, Lord Raglan on hero myths and on literature as a whole, and Northrop Frye and Stanley Edgar Hyman on literature generally. As literary critics, these myth-ritualists have understandably been concerned less with myth itself than with the mythic origin of literature. Works of literature are interpreted as the outgrowth of myths once tied to rituals. For those literary critics indebted to Frazer, as (are) the majority, literature harks back to Frazer's second myth-ritualist scenario. "The king must die" becomes the familiar summary line.

For literary myth-ritualists, myth becomes literature when myth is severed from ritual. Myth tied to religious literature; myth cut off from ritual is secular literature, or plain literature. When tied to ritual, myth can serve any of the active functions ascribed to it by myth-ritualists. Bereft of ritual, myth is reduced to mere commentary.

René Girard

In The Hero, ... Lord Raglan extends Frazer's second myth-ritualist scenario by turning the king who dies for the community into a hero. In Violence and the Sacred and many subsequent works, the French-born, American-resident literary critic René Girard (b. 1923) offers an ironic twist to the theory of Raglan, himself never cited. Where Raglan's hero is willing to die for the community, Girard's hero is killed or exiled by the community for having caused their present woes. Indeed, the "hero" is initially considered a criminal who deserves to die. Only subsequently is the villain turned into a hero, who, as for Raglan, dies selflessly for the community. Both Raglan and Girard cite Oedipus as their fullest example. (Their doing so makes neither a Freudian. Both spurn Freud.) For Girard, the transformation of Oedipus for reviled exile in Sophocles' Oedipus the King to revered benefactor in Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus typifies the transformation from criminal to hero.

Yet this change is for Girard only the second half of the process. The first half is the change from innocent victim to criminal. Originally, violence erupts in the community. The cause is the inclination, innate in human nature, to imitate others and thereby to desire the same objects as those of the imitated. Imitation leads to rivalry, which leads to violence. Desperate to end the violence, the community selects an innocent member to blame for the turmoil. This "scapegoat" can be anyone and can range from the most helpless member of society to the most elevated, including, as with Oedipus, the king. The victim is usually killed, though, as with Oedipus, sometimes exiled. The killing is the ritualistic sacrifice. Rather than directing the ritual, as for Frazer, myth for Girard is created after the killing to excuse it. Myth comes from ritual, as for Smith, but it comes to justify rather than, as for Smith, to explain the ritual. Myth turns the scapegoat into a criminal, who deserved to die, and then turns the criminal into a hero, who has died voluntarily for the good of the community.

Girard's theory, which cent(er)s on the place of the protagonist in society, would seem hopelessly inapplicable to the myth of Adonis. Adonis hardly dies willingly or selflessly. The very worlds he inhabits — the woods and the Underworld — seem as far removed from society as can be. ... [T]his myth will nevertheless be interpreted socially, and Girard's own interpretation of the myth of Oedipus will be presented.

While Girard never cites Raglan, he does regularly cite Frazer. Confining himself to Frazer's second myth-ritualist scenario, Girard lauds Frazer for recognizing the key primitive ritual of regicide but berates him for missing the real origin and function. For Frazer, sacrifice is the innocent application of a benighted, pre-scientific explanation of the world: the king is killed and replaced so that the god of vegetation, whose soul resides in the incumbent, can either retain or regain his health. The function of the sacrifice is wholly agricultural. There is no hatred of the victim, who simply fulfills his duty as king and is celebrated throughout for his self-sacrifice. According to Gerard, Frazer thereby falls for the mythic cover-up. The real origin and function of ritual and subsequent myth are social rather than agricultural....

Walter Burkert

Perhaps the first to temper the dogma that myths and rituals are inseparable was the American anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn. The German classicist Walter Burkert (b. 1031) has gone well beyond Kluckhohn in not merely permitting but outright assuming the original independence of myth and ritual. He maintains that when the two do come together, they do not just serve a common function, as Kluckhohn assumes, but reinforce each other. Myth bolsters ritual by giving merely human behavior a divine origin: do this because the gods did or do it. Conversely, ritual bolsters myth by turning a mere story into prescribed behavior of the most dutiful kind: do this on pain of anxiety, in not punishment. Where for Smith myth serves ritual, for Burkert ritual equally serves myth.

Like Gerard, Burkert roots myth in sacrifice and roots sacrifice in aggression, but he does not limit sacrifice to human sacrifice, and he roots sacrifice itself in hunting — the original expression of aggression. Moreover, myth for Burkert functions not to hide the reality of sacrifice, as for Girard, but on the contrary to preserve it and thereby to retain its psychological and social effects. Finally, Burkert connects myths not only to rituals of sacrifice but also, like Harrison, to rituals of initiation. Myth here serves the same socializing function as ritual.

Ritual for Burkert is "as if" behavior. To take his central example, the "ritual" is not the customs and formalities involved in actual hunting but dramatized hunting. The function is no longer that of securing food, as for Frazer, for the ritual proper arises only after farming has supplanted hunting as the prime source of food:

Hunting lost its basic function with the emergence of agriculture some ten thousand years ago. But hunting ritual had become so important that it could not be given up.

(Burkert, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual, p. 55)

The communal nature of actual hunting, and of ritualized hunting thereafter, functioned to assuage anxiety over one's own aggression and one's own mortality, and at the same time to cement a bond among participants. The functions were psychological and sociological, not agricultural.

The myth of Adonis would present an ironic case for Burkert. Not only is Adonis' hunting solitary rather than communal, but Adonis is scarcely a real hunter, let alone one racked by anxiety. For him, hunting is more a sport than a life-and-death encounter. Therefore hunting can hardly abet him either psychologically or socially. Yet his saga can still function as a warning to others....

Robert Segal, Ph.D. specializes in theories of myth, religion, and Gnosticism. He is the author of Myth: A Very Short Introduction, The Poimandres as Myth, Religion and the Social Sciences, Explaining and Interpreting Religion, Joseph Campbell, and Theorizing about Myth. He is the editor of The Gnostic Jung, The Allure of Gnosticism, The Myth and Ritual Theory, and Hero Myth Reader. He is an advisor for PARABOLA magazine. Dr. Segal hold is Chair of Religious Studies at Kings College, the University of Aberdeen. Read more about him here. Robert Segal, Ph.D. specializes in theories of myth, religion, and Gnosticism. He is the author of Myth: A Very Short Introduction, The Poimandres as Myth, Religion and the Social Sciences, Explaining and Interpreting Religion, Joseph Campbell, and Theorizing about Myth. He is the editor of The Gnostic Jung, The Allure of Gnosticism, The Myth and Ritual Theory, and Hero Myth Reader. He is an advisor for PARABOLA magazine. Dr. Segal hold is Chair of Religious Studies at Kings College, the University of Aberdeen. Read more about him here.

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|