|

Mrs. Bluebeard's Husbands:

Horror's Renewed Masculine Image

by Mitch Finn, MA

Film tends to preserve our archetypal heritage through the retelling of fairy tales in contemporary forms. "Cinderella" and "Beauty and the Beast" are two of the more common tales being remade. But there are periods when the significantly more macabre story of "Bluebeard" has come to our contemporary awareness. This fairy tale, which had various versions in the oral tradition of folk tales, functions as a template for many modern narratives, in both subtle and clear-cut ways. Bluebeard figures prominently in the horror and thriller genres, and continues to be a compelling source of investigation for storytellers, even as the particular images of horror continue to change. Film tends to preserve our archetypal heritage through the retelling of fairy tales in contemporary forms. "Cinderella" and "Beauty and the Beast" are two of the more common tales being remade. But there are periods when the significantly more macabre story of "Bluebeard" has come to our contemporary awareness. This fairy tale, which had various versions in the oral tradition of folk tales, functions as a template for many modern narratives, in both subtle and clear-cut ways. Bluebeard figures prominently in the horror and thriller genres, and continues to be a compelling source of investigation for storytellers, even as the particular images of horror continue to change.

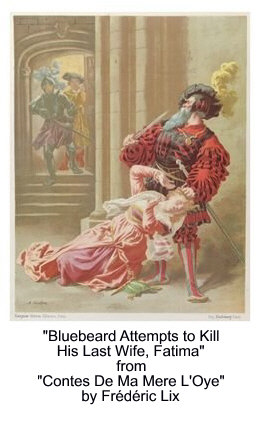

The tale according to Charles Perrault involves the wedding of a young maiden to a mysterious, widowed, exotic bearded aristocrat. She is sent to marry him by her family, assuming she will do well with such a weathy man. They wed, and he takes her to his castle, and gives her charge over a key which she is forbidden to use on the door of a secret room, a cellar door. He tells her that if she disobeys him and goes to where she is forbidden, that he will be very angry and she will incur the depth of his wrath. Conveniently, Bluebeard goes away on business for six weeks, and his wife trips over herself in curiosity to open the secret door. Inside she finds the six mutilated corpses of his former wives. Startled, she drops the key into a pool of blood, creating a stain that will not vanish, and for the life of her, she can not rub out. Six weeks later, he returns and demands to see the key. Of course, it is stained, and he knows where she has been. He allows her a quarter of an hour to say her prayers, and begins to sharpen his knives. She calls for her sister to summon her brothers, a pair of musketeers. The brave brothers arrive in the nick of time to enter the castle and slay the monstrous count. (Tartar, 2004)

In many ways, "Bluebeard" is the inverse story of "Beauty and the Beast." Where in "Beast," the maiden uses her compassion to break the curse of a man who is a monster on the outside but a prince on the inside, in "Bluebeard," she uses her compassionate curiosity to attempt to break the curse of a man who is apparently a prince, but is deceitfully a monster. This is a template for horror in that the heroine is wedded to the cursed man, unconscious, and finds herself in entrapping, irreversible, inescapable, and tragic fate.

Perhaps film-goers recognize this tale from some collective memory. The template of this tale has been made many times into film, twelve times alone in the 1940's, including George Cukor's Gaslight, Fritz Lang's Secret Beyond the Door, and twice by Alfred Hitchcock in Rebecca (1940), and Notorious (1946). The tale includes a wife who marries hastily, in seductive infatuation, and she is summarily forbidden to understand certain secrets of her husband's past, usually murderous. In each case, there is a forbidden cellar, or room, which contains the forbidden thing. This secret always turns out to be the man's undoing. The template is also prominent in more recent horror and psychological thrillers, with some minor twists, including the rogue James Bond picture, Never Say Never Again (1983), Jane Campion's The Piano (1993), Goldie Hawn in Deceived (1991), Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980), and Skeleton Key (2005).

In her book, Secrets Beyond the Door: The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives (2004), Maria Tartar develops the thesis that this recurring tale provides a morality tale about the importance of woman's curiosity. It is about the need to know, to discover, herein literalized as the skeletons in the closet. She writes, "Modern horror may also be tapping into an earlier narrative tradition, one that included folktales such as "Bluebeard," "The Robber Bridegroom," or "The Fitcher's Bird," in which women figure as investigative agents (uncovering crimes and outwitting villains), while men function as the criminal guardians of the dark, secret places." (2004, p. 57) It is important to note that horror is not about the struggle with some abstract notion of evil. It is about the struggle to attain knowledge, to seek, to discover secrets, and the feelings contained in those secrets, which only at face value appear dark and monstrous. (2004), Maria Tartar develops the thesis that this recurring tale provides a morality tale about the importance of woman's curiosity. It is about the need to know, to discover, herein literalized as the skeletons in the closet. She writes, "Modern horror may also be tapping into an earlier narrative tradition, one that included folktales such as "Bluebeard," "The Robber Bridegroom," or "The Fitcher's Bird," in which women figure as investigative agents (uncovering crimes and outwitting villains), while men function as the criminal guardians of the dark, secret places." (2004, p. 57) It is important to note that horror is not about the struggle with some abstract notion of evil. It is about the struggle to attain knowledge, to seek, to discover secrets, and the feelings contained in those secrets, which only at face value appear dark and monstrous.

Following this Blubeard-like tradition of folktales, the investigative woman archetype in film dominated mainstream horror in the seventies, eighties and nineties. Carol Clover, in her book Men Women and Chainsaws , (1992) called this motif the "Final Girl," which dominated the era's most popular series: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), Friday the Thirteenth (1980), Halloween (1978), Alien (1979), Hellraiser (1986), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Candyman (1992), Scream (1995), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1996), and The Ring (2002). "The Final Girl", who always ended as the sole survivor after all her friends were knocked off, was the investigative force who went into the creepy secret places, sought to understand the nature of the killer, ghost or monster, and in the end, found the fortitude to either fight the monster, or the dexterity to escape danger. While Bluebeard's wife relied on the help of her brothers to rescue her, rescue attempts in modern horror are traditionally bound to failure. In the process, the "Final Girl" became violent, aggressive, and a warrior of great ability. The modern image of woman in horror is one who has the agency to handle the proverbial monsters from the id. , (1992) called this motif the "Final Girl," which dominated the era's most popular series: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), Friday the Thirteenth (1980), Halloween (1978), Alien (1979), Hellraiser (1986), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Candyman (1992), Scream (1995), I Know What You Did Last Summer (1996), and The Ring (2002). "The Final Girl", who always ended as the sole survivor after all her friends were knocked off, was the investigative force who went into the creepy secret places, sought to understand the nature of the killer, ghost or monster, and in the end, found the fortitude to either fight the monster, or the dexterity to escape danger. While Bluebeard's wife relied on the help of her brothers to rescue her, rescue attempts in modern horror are traditionally bound to failure. In the process, the "Final Girl" became violent, aggressive, and a warrior of great ability. The modern image of woman in horror is one who has the agency to handle the proverbial monsters from the id.

These gender-assigned roles seemed to be set in stone for three decades. It is such a widely known cliché that it is worth parody — the portrayal of men as sadistic perpetrators and abusers, and women as victims/heroes/analysts, of the repressed. Clover notes that horror films like Halloween (1978), or Nightmare on Elm Street (1983), or Friday the Thirteenth (1980), adore the image of the suffering, emotional woman. Death scenes of women are gorier and protracted. Deaths of guys, though they do exist aplenty, tend to be short, and have abrupt, clean cutaways. She suggests that film did not know how to portray the image of a suffering man in this era. It goes to show that we do not know how to take in the knowledge of a man in great pain, proving the cultural dictum that "boys don't cry," in essence perpetuating that stereotype. (1992) These gender-assigned roles seemed to be set in stone for three decades. It is such a widely known cliché that it is worth parody — the portrayal of men as sadistic perpetrators and abusers, and women as victims/heroes/analysts, of the repressed. Clover notes that horror films like Halloween (1978), or Nightmare on Elm Street (1983), or Friday the Thirteenth (1980), adore the image of the suffering, emotional woman. Death scenes of women are gorier and protracted. Deaths of guys, though they do exist aplenty, tend to be short, and have abrupt, clean cutaways. She suggests that film did not know how to portray the image of a suffering man in this era. It goes to show that we do not know how to take in the knowledge of a man in great pain, proving the cultural dictum that "boys don't cry," in essence perpetuating that stereotype. (1992)

This is precisely why men have suffered so in horror. The genre is a genre of affect; it psychologically requires the protagonist to accept the affects implied by the dark initiations of the narrative's traumatic events. Horror requires screams, tears, and fear. It is a genre of angst, not of macho pretensions. In the traditional slasher movie, macho, vain, materialistic or egotistical guys are usually among the first to get knocked off the no-name ensemble cast. What is essential in all horror protagonists — humility, cleverness and wit, have been absent from horror's depiction of men. Adult males have not been emotional or curious, and have not found heroic portrayals in horror. Rather, their secret emotions, everything they cannot say or bear to articulate is in fact the origin of the beast, the shadow itself. Men are much more likely to be portrayed as boogymen and psychopaths — keepers of the unspeakable secrets.

This decade last, however, is showing a significant shift in this horror gender gap. A landmark in the portrayal of men's emotions on screen was in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001). The frank portrayal of an emotional Frodo, Sam, Aragorn, Gandalf and the rest of the fellowship was far beyond the rather formal, terse masculine in the writing of Tolkien. Also contributing to this mainstream shift is the depiction of the fall of Anakin Skywalker into Darth Vader in the new Star Wars trilogy (1999). From the arrogant, selfish kid into a repressed father full of secrets he cannot bear or even remember. Between the nineties to present, film has gone from Tom Hank's "Are you crying? There's no crying. There's no crying in baseball!" in A League of Their Own (1992), to Hanks' memorable weeping in Philadelphia (1993), and even Spielberg's war epic, Saving Private Ryan (1998). The associations into film, and media in general, are many, and these examples only scratch the surface.

Although these changes in the depiction of masculine affects have gone through significant strides in mainstream media, horror seems to have had a long-standing, and defiant prohibition against the male protagonist. The changes that became necessary for this taboo to be broken were informed by the changes in the collective expression of masculinity. However, we are now beginning to see a new male figure in horror in this post-Fox Mulder era. Just as Mulder and Scully showed while investigating The X- Files, (1993) women do not have sole lease on the suffering investigator role, but share it with the masculine figure, forming a balance in the portrayal of masculine and feminine curiosity for the monstrous unknown. As Carol Clover presaged at the time of her writing in 1992, these gender roles were not fixed, but were pregnant with change, "We may expect horror films of the future to feature "Final Boys" as well as "Final Girls" (Pauls as well as Paulines)," (1992, p. 63). This is precisely what has happened. Although these changes in the depiction of masculine affects have gone through significant strides in mainstream media, horror seems to have had a long-standing, and defiant prohibition against the male protagonist. The changes that became necessary for this taboo to be broken were informed by the changes in the collective expression of masculinity. However, we are now beginning to see a new male figure in horror in this post-Fox Mulder era. Just as Mulder and Scully showed while investigating The X- Files, (1993) women do not have sole lease on the suffering investigator role, but share it with the masculine figure, forming a balance in the portrayal of masculine and feminine curiosity for the monstrous unknown. As Carol Clover presaged at the time of her writing in 1992, these gender roles were not fixed, but were pregnant with change, "We may expect horror films of the future to feature "Final Boys" as well as "Final Girls" (Pauls as well as Paulines)," (1992, p. 63). This is precisely what has happened.

In the 2002 cult hit Jeepers Creepers, an Illinois crop demon called "The Creeper" is on his one-month flesh-feeding spree that occurs every twenty-third year. The heroes turn out to be a brother and sister duo, Dari and Trish, who run into the mayhem while returning home from spring break. Dari actually is the more inquisitive of the two, and propels the action into a dark descent with his curious do-gooder attitude.

In Wrong Turn (2003), a young ensemble wind up on a deserted West Virginia road that is preyed upon by a trio of male cannibalistic inbreeds. After their friends are knocked off, there emerges a boy-girl duo. Desmond, a young doctor, and Jessie, a college girl, both end up being the co-survivors and work in violent tandem to defeat the monsters in their own lair of goo.

Similarly, in Wes Craven's update on the werewolf sub-genre, Cursed (2005), grown brother and sister orphans, Jimmy and Ellie, are set to task to discover the secrets behind the curse of the beast. One night both are bitten by a werewolf and find themselves developing new strengths and abilities over the course of the month building up to the next lunar cycle. To break their curse, they have to find and destroy the one who bit them. Cursed borrows from the whodunit plots as the siblings choose among their friends the likely suspects. Once they find the original beast, it is as a tandem that they learn to control and implement their animal powers to destroy him.

Perhaps most tellingly, in the remake of House of Wax (2005), the heroes turn out to be not just brother Nick and sister Carley, but fraternal twins struggling in their sibling rivalry. Their twinship poetically mirrors the villains of the picture. Conjoined at birth, but since separated, Bo and Vincent are the only inhabitants of a town made entirely of wax. The life-like authenticity of their figures are due to their using live people as their models. The evil twins manage to whack Paris Hilton and the rest of the ensemble before the heroic twins discover the secret of the town on the way to defeating them and melting down the entire wax complex.

The heroic twins suggest a new, balanced archetypal configuration, like the Gemini, or the Popul Voh twins of Mayan lore. Here, balanced between genders, are representations for both masculine and feminine curiosity. Twins in unity like this suggest a renewed and cooperative harmonious dualism. Here, the primary difference is gender, but also can be a twinning balance of light and dark, spirit and body, action and thought. The heroic twins suggest a new, balanced archetypal configuration, like the Gemini, or the Popul Voh twins of Mayan lore. Here, balanced between genders, are representations for both masculine and feminine curiosity. Twins in unity like this suggest a renewed and cooperative harmonious dualism. Here, the primary difference is gender, but also can be a twinning balance of light and dark, spirit and body, action and thought.

Apparently Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, the famed collectors of oral folk-telling of the nineteenth century, were selective in their fairy tale cannon. (2004) Some tales they excluded out of their own preferences or biases. The apocryphal Grimm tales include tales of masculine curiosity as well in the fashion of Bluebeard, which figured a bridegroom who seeks to understand his new bride. The meaning of health and beauty on the outside, but a forbidden secret, or hidden form, she can take. This depiction of the curious masculine remained repressed in the West until the latest trends in horror. Indications are, however, that perhaps this tale has been better preserved in the East in their folklore and horror.

In the Japanese fairy tale "The Crane's Gift," a woodcutter is walking through the forest and comes across a crane trapped in a cage, crying. The woodcutter pities the animal, and frees it, before returning home to his wife. A young beggar woman latter knocks on his door, and it is cold outside, so they invite her to stay. It turns out to be a cold winter and she stays a long time. The young woman says she will make a gift of a cloth for the couple to show her appreciation. She asks for a room to work her loom in and bodes them to never open the door when she's working. They do as she asks, and she emerges a day later with the most spectacular cloth. They sell the cloth in town for a handsome price. And the next day, and the next, she produces more cloth, each more spectacular than the last. Everyone in town is curious to see how the silken threads are woven, and they encourage the woodcutter to peek through the crack of the door. At last he cannot resist himself and looks through, and sees a crane at the loom. She stops weaving immediately, and flies out the window.

It is noteworthy that for the Japanese, the curious seeker is a male in the popular Ringu (1998) pictures, but when the franchise was remade by Hollywood for an American audience as The Ring (2002), the protagonist was reverted to the more traditional feminine figure.

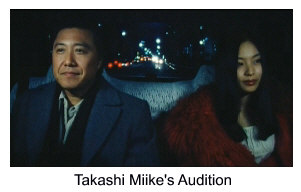

Astonishingly, there is a Japanese "Bluebeard" movie in which Bluebeard is feminine, directly reversing the fairy tale template from the beginning. Here, the dark places are guarded by a feminine figure. Takashi Miike's Audition (2001) is about a widower named Ayoma, who seven years after the loss of his wife, seeks to marry another to salve his loneliness. He pines for a woman of class, sophistication and talent. His friend arranges to have an audition for a new television show, a front for Ayoma's mate selection. After rejecting many tryouts, in walks Asami, a former ballet dancer, and Ayoma is immediately head-over-heels. He asks her to date, and things move quickly along despite the warnings and judgement of everyone around him who mistrusts her. While their gut instincts are dead-on, their urges for him to stop seeing her are useless. Ayoma's friend cannot verify anything about her resumé, her past, or any contact she claims. Astonishingly, there is a Japanese "Bluebeard" movie in which Bluebeard is feminine, directly reversing the fairy tale template from the beginning. Here, the dark places are guarded by a feminine figure. Takashi Miike's Audition (2001) is about a widower named Ayoma, who seven years after the loss of his wife, seeks to marry another to salve his loneliness. He pines for a woman of class, sophistication and talent. His friend arranges to have an audition for a new television show, a front for Ayoma's mate selection. After rejecting many tryouts, in walks Asami, a former ballet dancer, and Ayoma is immediately head-over-heels. He asks her to date, and things move quickly along despite the warnings and judgement of everyone around him who mistrusts her. While their gut instincts are dead-on, their urges for him to stop seeing her are useless. Ayoma's friend cannot verify anything about her resumé, her past, or any contact she claims.

What begins as a light romantic comedy becomes horrific as the secrets of Asami's past come to light. Behind her persona of demure obedience is a sadistic, brutal femme fatale. Ayoma tries to put the pieces together, trying to find her, and stumbles across her old dance studio, now boarded up and condemned. This is Miss Bluebeard's secret chamber. He finds her former ballet teacher there playing piano. He is deformed, carrying the scars of her wrath. Following the trail of murders, he then finds himself subject to her tortures and she incapacitates him and begins to poke out his eyes with acupuncture needles and saw off his feet with piano wire. She, in fact, is re-enacting the tortures that she suffered on people close to her. During all this, he envisions her life of tortures, remembers all the traumatic things that happened to her, all the things he wanted to forget, but now only too painfully remembers. Like Bluebeard's wife, who had her brothers come to the rescue, his son comes and kills her.

A flip on old, typical American depictions on the horror genre, Audition (2001) presents a masculine form of curiosity for dark secrets and its concomitant suffering and victimization. This trend is beginning to bleed into the West as well in a few incipient examples. Reasons for this change to a focus on a suffering masculine figure may prove to be indicative of an increasing collective sensitivity to misandry, as indicated by other recent publications such as Angry Young Men: How Parents, Teachers, and Counselors Can Help "Bad Boys" Become Good Men , Abused Men: The Hidden Side of Domestic Violence , Abused Men: The Hidden Side of Domestic Violence , and The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism Is Harming Our Young Men , and The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism Is Harming Our Young Men , or else a renewed consciousness of the emotional struggles of men. , or else a renewed consciousness of the emotional struggles of men.

Eli Roth's Hostel (2005) features a cameo by Audition director Miike. In the DVD's commentary, Roth said he was inspired by Miike's hardcore brand of horror. Hostel not only reintroduced hard graphic gore to horror, but focused on the tortures of young men backpacking in Slovakia. Olie, Josh and Paxton are lured by the promises of endless erotic pleasure and intoxicated by a bevy of naked European hardbodies at the local spa. Resembling the irresistible songs of the sirens, the promise of erotic pleasure turns into thanatotic hell, as the models they are attracted to lead them to death chambers. The secret rooms turn out to be torture chambers run by the Russian mafia for those wealthy enough to afford the catharsis of their homicidal urges. It is also fitting that their hostel room number is 237, the same number of the forbidden room in the movie of The Shining (1980). The hidden rooms again symbolize the gateway to forbidden knowledge; in this case, to discovering one's own psychopathy. The "Final Boy" turns out to be Paxton, a reluctant victim/hero, sacrificing fingers with his innocence.

The indie horror film Saw (2004) also shows the suffering investigative male in detail. Adam and Dr. Gordon are chained to pipes in a dungeon of tortures. The life-sized puzzle box they find themselves in is orchestrated by a mastermind named Jigsaw who gets his meaning by lecturing sinners by placing them in predicaments whereby they either have to torture themselves or others in hopes of reprieve. Salvation from these tortures is attained by the characters' growing realizations about themselves and confessions they need to make in order to escape that involves physical sacrifice. There are several men in investigative roles, as Adam and Dr. Gordon try to put the jigsaw pieces together on the inside, and an obsessed police detective tries to track down Jigsaw from the outside. The "Final Boy" turns out to be Dr. Gordon, who severs his own foot with a hacksaw to escape. The indie horror film Saw (2004) also shows the suffering investigative male in detail. Adam and Dr. Gordon are chained to pipes in a dungeon of tortures. The life-sized puzzle box they find themselves in is orchestrated by a mastermind named Jigsaw who gets his meaning by lecturing sinners by placing them in predicaments whereby they either have to torture themselves or others in hopes of reprieve. Salvation from these tortures is attained by the characters' growing realizations about themselves and confessions they need to make in order to escape that involves physical sacrifice. There are several men in investigative roles, as Adam and Dr. Gordon try to put the jigsaw pieces together on the inside, and an obsessed police detective tries to track down Jigsaw from the outside. The "Final Boy" turns out to be Dr. Gordon, who severs his own foot with a hacksaw to escape.

Saw II (2005) puts the Jigsaw's suffering tasks to an ensemble of players. A near-remake, it is interesting what happens to the villain. While villains as great and mysterious as Jigsaw seem to be diabolically immortal through a series' sequels, Saw II puts a twist on this convention. Jigsaw is dying of cancer, but has an apprentice who is set to take over putting sinners in ironic puzzle boxes that will likely be the story of them. His apprentice is a female, suggesting that not only are more males being represented as the suffering analysts, but more females are becoming guardians of the secret room — in this case, Jigsaw's lair. There is a police detective analyst on the outside, but the real "Final Boy" is his son on the inside of the puzzle, a knowledgeable teenager who is the only one that follows Jigsaw's rules for escaping.

If Saw and Hostel were made in the eighties they most certainly would have been portrayed with female heroines rather than their male counterparts. These recent twists, however, reach back to a perhaps older, mythic narrative than "Bluebeard." They harken to the tortured trials of another curious male seeker of dark forbidden realms, the Greek Orphic cycle.

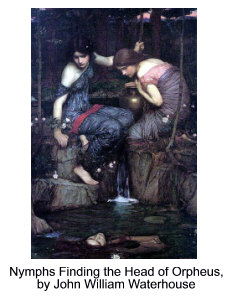

Orpheus, son of Apollo, was a great poet and musician whose passionate singing could even move trees and inanimate objects to great emotional displays. He lived happily with his beautiful wife, Eurydice, until she was tragically bitten by an asp and died. Unable to let her go, Orpheus journeyed to the underworld to retrieve his beloved. Hades, impressed by his musical talents, agreed to let Eurydice return to the living, as long as

Orpheus agreed to not look upon her gorgeous figure while on the trail out of hell. With the aide of Hermes, Orpheus led Eurydice on the way out, but just as he was at the exit of Hades, he could not stand the temptation of not seeing her any longer, and looked back. She immediately sank back into the underworld, this time to remain forever. Orpheus was inconsolable, and sought exile to distant lands, intending never again to set his sights on another woman. Ironically, he ended up in the forest realm of the Bacchae, nature witches who worshiped Dionysus. As was their ritual, they tore him limb from limb in sacrifice to re-enact the dismemberment of the god of ecstasy. Later, it is said that Orpheus' dismembered head was seen floating in streams, still singing his love song. Orpheus, son of Apollo, was a great poet and musician whose passionate singing could even move trees and inanimate objects to great emotional displays. He lived happily with his beautiful wife, Eurydice, until she was tragically bitten by an asp and died. Unable to let her go, Orpheus journeyed to the underworld to retrieve his beloved. Hades, impressed by his musical talents, agreed to let Eurydice return to the living, as long as

Orpheus agreed to not look upon her gorgeous figure while on the trail out of hell. With the aide of Hermes, Orpheus led Eurydice on the way out, but just as he was at the exit of Hades, he could not stand the temptation of not seeing her any longer, and looked back. She immediately sank back into the underworld, this time to remain forever. Orpheus was inconsolable, and sought exile to distant lands, intending never again to set his sights on another woman. Ironically, he ended up in the forest realm of the Bacchae, nature witches who worshiped Dionysus. As was their ritual, they tore him limb from limb in sacrifice to re-enact the dismemberment of the god of ecstasy. Later, it is said that Orpheus' dismembered head was seen floating in streams, still singing his love song.

Just as there are mythic images of the curious feminine figure in Pandora, Eve, and Bluebeard's wife, we find there are old mythic masculine figures of curiosity for forbidden knowledge in spite of wretched consequences being revived in recent horror films. The quest for knowledge can be a lonely and dangerous quest into the darkest places in the soul. It seems that all of life is an endless seduction into further and further reaches into the vast abyss of the unknown. The unknown alternately appears as a lover, seducing us into the unconscious, or else appearing as a monster, meant to frighten us away from the secrets stowed away. As Asami in Audition (2001) tells her courter, "I want you to know everything about me," she says, "Love only me." We may read this as the voice of the unconscious — it desires to be known, it seeks relationship with us. It is our own curiosity and empathy and care that allow that knowledge, that relationship to occur, to create greater consciousness. In other words, if we allow ourselves to be in a relationship with the unknown and do not destroy ourselves, or each other, in the process, we may find ourselves capable of transformation.

The secret of Bluebeard is that he wants his wife to find the room. He gives her the key, tempts her as Pandora or Eve were once tempted. Bluebeard is a suffering figure, a bewitched man, and he can only find redemption by revealing his darkest secret, the one he cannot stand to articulate. What would happen if he does not try to murder her? What happens if the two do not break up? What happens if they are able to talk about the unbearable trauma he has to hide? The secret of Bluebeard is that he wants his wife to find the room. He gives her the key, tempts her as Pandora or Eve were once tempted. Bluebeard is a suffering figure, a bewitched man, and he can only find redemption by revealing his darkest secret, the one he cannot stand to articulate. What would happen if he does not try to murder her? What happens if the two do not break up? What happens if they are able to talk about the unbearable trauma he has to hide?

A hint of this possible outcome unravels in another recent film, and suggests a new paradigm, another chapter to the ongoing quest for understanding the dark secrets and the past history of violence in relationships. David Cronenberg's A History of Violence (2005) chronicles the tale of Tom Stall and his family. They are apparently an ordinary family living in mid-western, Anytown, U.S.A.. Tom and his wife work at a coffee shop and all is normal with the world until a pair of murdering thugs try to rob them. Tom attacks the men with a coffee pot and kills these professional killers in short order. Questions arise as to why Tom is so good at killing people, and it is suggested by visiting mafia thugs that he is in fact a great killer named Joey Cusak. Soon it is realized that the situation is not merely a case of mistaken identity and the family struggles with the secrets of the father's past history. It turns out that the family can change because of this revelation — the teenage son's confidence grows at school and he learns to stand up to his bullies. The married couple's sex life becomes more fiery, violent, risky. Tom's family survives because they have relationships, they can find ways to dialog about these kinds of problems. As a family, they are better equipped for welcoming these new dimensions of the father's personality. Where once the husband would have to try to kill his wife and child as in The Shining (1980), this model for the family of the new millennium can sit down, share a meal, and figure out how to live with each other.

Books Referenced

Films Referenced

- Barker, C. (Director). (1987). Hellraiser.

- Bouseman, J. (Director). (2005). Saw II.

- Campion, Jane (Director). (1993). The Piano.

- Carpenter, J. (Director). (1978). Halloween.

- Carter, C. (Creator). (1993). The X-Files. Fox Television.

- Collet-Sera, J. (Director). (2005). House of Wax.

- Craven, Wes (Director). (1984). Nightmare on Elm Street.

— (1995). Scream.

—(2005). Cursed.

- Cronenberg, D. (Director). (2005). A History of Violence.

- Cukor, George (Director). (1942). Gaslight.

- Cunningham, Sean S. (Director). (1980). Friday the Thirteenth.

- Demme, J. (Director). (1993). Philadelphia.

- Gillespe, J. (Director). (1997). I Know What You Did Last Summer.

- Harris, Damien (Director). (1991). Deceived.

- Hitchcock, Alfred (Director). (1940). Rebecca.

— (1946). Notorious.

- Hooper, T. (Director). (1974). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

- Jackson, Peter. (Director). (2001). The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

- Kershner, Irvin (Director). (1983). Never Say Never Again.

- Kubrick, Stanley (Director). (1980). The Shining.

- Lang, Fritz (Director). (1948). Secret Beyond the Door.

- Lucas, George. (Director). (2005). Star Wars, Episode III: Revenge of the Sith.

- Marshall, Penny. (Director). (1992). A League of Their Own.

- Miike, Takashi . (Director). (2001). Audition.

- Nakata, H. (Director). (1998). Ringu.

- Rose, B. (Director). (1992). Candyman.

- Roth, E. (Director). (2005) Hostel.

- Salva, V. (Director) & Luse, T. (Producer). (2001). Jeepers Creepers.

- Schmidt, R. (Director). (2003). Wrong Turn.

- Scott, R. (Director) & Hill, W. (Producer). (1979). Alien.

- Softly, Ian (Director). (2005). Skeleton Key.

- Spielberg, Steven. (Director). (1998). Saving Private Ryan.

- Verbinski, G. (Director). (2002). The Ring.

- Wan, J. (Director). (2004). Saw.

Mitch Finn, MA, Mitch Finn, MA, is a psychotherapist practicing in Houston, and is currently a doctoral candidate in Mythological Studies at Pacifica Graduate Institute. His masters thesis, Lessons from the Dark: Trauma and Soul Retrieval in Horror Cinema, examined the cultural fascination with horror mythopoesis.

Read more by Mitch Finn at his website mitchfinn.com

Read Bluebeard by Charles Perrault

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|